Usuario:Jdvillalobos/pruebas

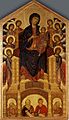

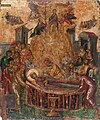

Mi pequeña pinacoteca[editar]

-

No es una pintura, pero es que...

Esta es una lista de las guerras y desastres antropogénicos por número de muertos. Registra los estimados mínimo y máximo de muertes, el nombre del acontecimiento, la ubicación, y el comienzo y el final de cada acontecimiento. Algunos sucesos traslapan categorías.

Guerras y conflictos armados[editar]

Las cifras de un millón o más muertes incluyen las muertes de civiles por enfermedades, hambruna, etc., así como muertes de soldados en batalla, masacres y genocidio. Donde solo esté disponible un estimado, aparecerá tanto en el máximo como en el mínimo. La lista es organzable.

| Estimado más bajo |

Estimado más alto |

Evento | Ubicación | De | a | Ver también | Porcentaje de la población mundial[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 000 000[2] | 72 000 000[3] | Segunda Guerra Mundial | Todo el mundo | 1939 | 1945 | World War II casualties and Second Sino-Japanese War[4] | 1.7%–3.1% |

| 30 000 000[5] | 70 000 000[cita requerida] | Mongol conquests | Eurasia | 1206 | 1368 | Mongol Empire | 17.1% |

| 30 000 000[5] | 30 000 000 | Late Yuan warfare and transition to Ming Dynasty | China | 1340 | 1368 | Ming Dynasty | 6.7% |

| 25 000 000[6] | 25 000 000 | Qing dynasty conquest of the Ming Dynasty | China | 1616 | 1662 | Qing Dynasty | 4.8% |

| 20 000 000[7] | 100 000 000[8][9][10][11][12] | Taiping Rebellion | China | 1851 | 1864 | Dungan revolt | 1.6%–8% |

| 15 000 000[13] | 65 000 000 (this estimate includes worldwide Spanish flu deaths)[14] |

Primera Guerra Mundial | Todo el mundo | 1914 | 1918 | World War I casualties | 0.8%–3.6% |

| 15 000 000[15] | 20 000 000[15] | Conquests of Timur-e-Lang | West Asia, South Asia, Central Asia, Russia | 1369 | 1405 | [16] | 3.4%–4.5% |

| 13 000 000[17] | 36 000 000[18] | An Lushan Rebellion | China | 755 | 763 | Medieval warfare | 5.5%–15.3% |

| 8 000 000[19][20] | 12 000 000 | Dungan revolt | China | 1862 | 1877 | Panthay Rebellion | 0.6%–0.9% |

| 5 000 000[cita requerida] | 30 000 000[cita requerida] | Conquests by the Empire of Japan | Asia | 1894 | 1945 | ||

| 5 000 000 [cita requerida] |

9 000 000[21] | Guerra Civil Rusa | Russia | 1917 | 1921 | Russian Revolution (1917), List of civil wars | 0.28%–0.5% |

| 2 500 000[22] | 5 400 000[23] | Second Congo War | Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1998 | 2003 | First Congo War | 0.06%–0.09% |

| 3 500 000 [cita requerida] |

7 000 000[24] | Napoleonic Wars | Europe, Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Ocean | 1803 | 1815 | Napoleonic Wars casualties | 0.4%–0.7% |

| 3 000 000 | 11 500 000[25] | Thirty Years' War | Holy Roman Empire | 1618 | 1648 | Religious war | 0.5%–2.1% |

| 3 000 000[26] | 7 000 000[26] | Yellow Turban Rebellion | China | 184 | 205 | Part of Three Kingdoms War | 1.3%–3.1% |

| 1 000 000 | 3 000 000 | Guerra Civil Nigeriana | Nigeria | 1967 | 1970 | Genocides in history | 0.03%-0.09% |

| 1 500 000[27] | 2 000 000[27] | Afghan Civil War | Afghanistan | 1979 | Present | Soviet-Afghan War, Taliban Era, and NATO Intervention. Death toll estimates through 1999 (2M) and 2000 (1.5M and 2M). | 0.06% |

| 3 000 000[28] | 4 000 000[28] | Deluge | Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth | 1655 | 1660 | Second Northern War | 0.6%–0.7% |

| 400 000[29] | 4 500 000[29] | Korean War | Korean Peninsula | 1950 | 1953 | Cold War | 0.1% |

| 800 000[30] | 3 000 000[31] | Vietnam War | Southeast Asia | 1955 | 1975 | Guerra Fría and First Indochina War | 0.08%–0.19% |

| 2 000 000 | 4 000 000[32] | French Wars of Religion | France | 1562 | 1598 | Religious war | 0.4%–0.8% |

| 2 000 000[33] [cita requerida] |

2 000 000 [cita requerida] |

Shaka's conquests | Africa | 1816 | 1828 | Ndwandwe–Zulu War | 0.2% |

| 1 000 000[34] | 2 000 000 | Second Sudanese Civil War | Sudán | 1983 | 2005 | First Sudanese Civil War | 0.02% |

| 1 000 000[35] | 3 000 000[36] | Crusades | Holy Land, Europe | 1095 | 1291 | Religious war | 0.3%–2.3% |

| 600 000[27] | 2 000 000[27] | Soviet War in Afghanistan | Afganistán | 1980 | 1988 | Guerra Fría | 0.012%–0.04% |

| 900 000 | 1 000 000 | Gallic Wars | France | 58 BC | 50 BC | Roman Empire | 0.90%–1.00% |

| 800 000 | 1 000 000 | Du Wenxiu Rebellion | China | 1856 | 1873 | ||

| 500 000[37] | 2 000 000[37] | Revolución mexicana | México, Estados Unidos | 1911 | 1920 | Pancho Villa and Columbus Raid | 0.03%–0.1% |

| 500 000[38][39] | 2 000 000[cita requerida] | Iran–Iraq War | Irán, Irak | 1980 | 1988 | Al-Anfal Campaign and Invasion of Kuwait | 0.01%–0.04% |

| 400 000 | 800 000 | Guerra de Secesión | Estados Unidos, Estados Confederados | 1861 | 1865 | 0.03%–0.06% | |

| 500 000 | 1 000 000 | Guerra Civil Española | España | 1936 | 1939 | 0.025%–0.05% | |

| 300 000[40] | 1 200 000[41] | Guerra paraguaya | Suramérica | 1864 | 1870 | Military history of South America and Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, Duke of Caxias | 0.02%–0.08% |

Genocidios y supuestos genocidios[editar]

Genocides with at least a million fatalities in the high estimate category are shown here. The United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) defines genocide in part as "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group". Determining what historical events constitute a genocide and which are merely criminal or inhuman behavior is not a clear-cut matter. In nearly every case where accusations of genocide have circulated, partisans of various sides have disputed the interpretation and details of the event, often to the point of promoting different versions of the facts. An accusation of genocide will almost always be controversial. Determining the number of persons killed in each genocide can be just as difficult, with political, religious and ethnic biases or prejudices often leading to downplayed or exaggerated figures. Some of accounts below may include ancillary causes of death such as malnutrition and disease, which may or may not have been intentionally inflicted.

The following list of genocides and alleged genocides should be understood in this context and not necessarily regarded as the final word on the events in question.

| Lowest estimate |

Highest estimate |

Event | Location | From | To | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 194 200[42] | 17 000 000 [43][44][45] |

Holocaust | Europe | 1941 | 1945 | With around 6 million Jews murdered as well as the genocide of the Romani: most estimates of Romani deaths are in the 200,000–500,000 range but some estimate more than a million.[46] A broader definition includes political and religious dissenters, 200,000 people with disabilities,[47] 2 to 3 million Soviet POWs, 5,000 Jehovah's Witnesses, 15,000 homosexuals and small numbers of mixed-race children (known as the Rhineland bastards), and millions of Polish and Soviet civilians, bringing the death toll to around 17 million.[43] See Holocaust, Porajmos, Generalplan Ost, Consequences of German Nazism |

| 2 582 000[48][49][50] | 8 000 000[51] | Holodomor (and Soviet famine of 1932–1933) | Ukrainian SSR | 1932 | 1933 | Holodomor was a famine in Ukraine caused by the government of Joseph Stalin, a part of Soviet famine of 1932–1933. Holodomor is claimed by contemporary Ukrainian government to be a genocide of the Ukrainians.

A March 2008, Ukraine and nineteen other governments[52] have recognized the actions of the Soviet government as an act of genocide. The joint statement at the United Nations in 2003 has defined the famine as the result of cruel actions and policies of the totalitarian regime that caused the deaths of millions of Ukrainians, Russians, Kazakhs and other nationalities in the USSR. On 23 October 2008 the European Parliament adopted a resolution[53] that recognized the Holodomor as a crime against humanity.[54] On January 12, 2010, the court of appeals in Kiev opened hearings into the "fact of genocide-famine Holodomor in Ukraine in 1932–33", in May 2009 the Security Service of Ukraine had started a criminal case "in relation to the genocide in Ukraine in 1932–33".[55] In a ruling on January 13, 2010 the court found Stalin and other Bolshevik leaders guilty of genocide against the Ukrainians.[56] |

| 2 000 000 [57] |

100 000 000 [58] |

European colonization of the Americas | Americas | 1492 | 1900 | Although heavily disputed,[59] some historians such as David Stannard and Howard Zinn consider the deaths caused by disease, displacement, and conquest of Native American populations during European settlement of North and South America as constituting an act of genocide (or series of genocides). The alleged genocidal aspects of this event are entwined with loss of life caused by the lack of immunity of Native Americans to diseases carried by European settlers (see Population history of American indigenous peoples).[60][61] Some estimates indicate case fatality rates of 80–90% in Native American populations during smallpox epidemics.[62] According to Noble David Cook, "There were too few Spaniards to have killed the millions who were reported to have died in the first century after Old and New World contact."[63] Stafford Poole wrote: "There are other terms to describe what happened in the Western Hemisphere, but genocide is not one of them. It is a good propaganda term in an age where slogans and shouting have replaced reflection and learning ..."[64] |

| 1,000,000 | 3,000,000 | Nigerian Civil War | Nigeria | 1967 | 1970 | Since the independence of Nigeria in 1960 the 3 ethnic groups, the Hausa, Yoruba, and Igbo, had always been fighting over control in the political realm. The Igbos seemed to have control over most of Nigeria's politics until the assassination of the then Igbo president Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi by Yoruba general Yakubu Gowon. With this the Igbos seceded from Nigeria and created the Republic of Biafra. The Igbos had the upper hand until late 1967 when food supplies were cut off. By mid 1968 50% of Igbos were starving and thousands more were being slaughtered by Hausa and Yoruba soldiers. In 1970 the Igbo's surrendered to the Nigerians and by then anywhere from 1 to 3 million Igbos had either starved or had been killed. |

| 1,000,000[65] | 3 000 000[65] | Cambodian Genocide | Cambodia | 1975 | 1979 | A 2010 de 09, no one has been found guilty of participating in this genocide, but on 16 September 2010 Nuon Chea, second in command of the Khmer Rouge and its most senior surviving member, was indicted on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity. He will face Cambodian and United Nations appointed foreign judges at the special genocide tribunal.[66][67] |

| 1 200 000[68] | 2 400 000[68] | Maafa | Atlantic Ocean | 16th century | 19th century | Historian Charles Pete Banner-Haley notes that slavery was "not intentionally genocidal" and "resulted in the creation of a New World Afro-American."[69] African slaves died in large numbers during transportation from Africa. The number could be more accurate if it included deaths during the acquisition of slaves in Africa and subsequent deaths in America. Before the 16th century the principal market for the warring African tribes that enslaved each other's populations was the Islamic world to the east.[70] Gustav Nachtigal, an eye-witness, believed that for every slave who arrived at a market three or four died on the way.[71] |

| 500 000[72] | 1 000 000[72] | Rwandan genocide | Rwanda | 1994 | 1994 | Hutu killed unarmed men, women and children. Some 50 perpetrators of the genocide have been found guilty by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, but most others have not been charged due to no witness accounts. Another 120,000 were arrested by Rwanda; of these, 60,000 were tried and convicted in the gacaca court system. Genocidaires who fled into Zaire (Democratic Republic of the Congo) were used as a justification when Rwanda and Uganda invaded Zaire (First and Second Congo Wars). |

| 500 000[73] | 3 000 000[74] | Expulsion of Germans after World War II | Europe | 1945 | 1950 |

With at least 12 million[75][76][77] Germans directly involved, it was the largest movement or transfer of any single ethnic population in modern history[76] and largest among the post-war expulsions in Central and Eastern Europe (which displaced more than twenty million people in total).[75] The events have been usually classified as population transfer,[78] or as ethnic cleansing.[79] Martin Shaw (2007) and W.D. Rubinstein (2004) describe the expulsions as genocide.[80] Felix Ermacora writing in 1991, (in line with a minority of legal scholars) considered ethnic cleansing to be genocide[81][82] and stated that the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans was genocide.[83] |

| 300 000[84] | 1 500 000[85] | Armenian Genocide | Anatolia | 1915 | 1923 | Usually called the First Genocide of the 20th century. Despite recognition by some twenty one countries as a genocide, Turkey disputes genocide by the Ottoman Empire. |

| 200 000[86] | 1 000 000[86] | Greek genocide | Anatolia | 1915 | 1918 | Disputed by Turkey, but considered a genocide. |

| 75 000[87][88] | 130 000[87][88] | Massacres of Poles by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army | Volhyn and Eastern Galicia | 1943 | 1944 | Systematical massacres perpetrated by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army on Polish civilians in the eastern part of the Polish Second Republic (Tarnopolski, Stanisławski, Lwowski and Wołyński voivodeships in borders of 1939, under German or Soviet occupation at the time). The victims toll includes also women, children and elderly people. The small minority of dead belong to different ethnic group (mostly Ukrainians protecting Polish peoples against assaults, but also Jews and Russians). Most of the victims were tortured prior to their death. Disputed by Ukrainians, but considered a genocide by the Polish authorities. |

| 26 000[89] | 3 000 000[89] | 1971 Bangladesh atrocities | East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) | 1971 | 1971 | Atrocities in East Pakistan by the Pakistani Armed Forces, leading to the Bangladesh Liberation War and Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, are widely regarded as a genocide against Bengali people, but to date no one has yet been indicted for such a crime. |

Campos y cárceles de concentración[editar]

| Muertes | Nombre | Administrado por | Lugar | Fecha | Notas, referencias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 800,000–1,500,000 | Auschwitz-Birkenau | Alemania Nazi | Oświęcim, Polonia | 1940–1945 | [90][91] |

| 700,000–1,000,000 | Treblinka | Alemania Nazi | Treblinka, Polonia | 1942–1943 | [92][93] |

| 480,000–600,000 | Bełżec | Alemania Nazi | Bełżec, Polonia | 1942–1943 | [94][95][96] |

| 350,000 | Majdanek | Alemania Nazi | Lublin, Polonia | 1942–1944 | [cita requerida] |

| 300,000 | Chełmno | Alemania Nazi | Chelmno, Polonia | 1941–1943 | [cita requerida] |

| 260,000 | Sobibór | Alemania Nazi | Sobibor, Polonia | 1942–1943 | [cita requerida] |

| 130,000–500,000 | Kolyma Gulag | Unión Soviética | Kolymá, Unión Soviética | 1932–1954 | [97] |

| 100,000 | Bergen-Belsen | Alemania Nazi | Belsen, Alemania | 1942–1945 | [cita requerida] |

| 55,000 | Neuengamme | Alemania Nazi | Hamburgo, Alemania | 1938–1945 | [cita requerida] |

| 82,600 to 700,000 | Jasenovac | NDH Ustaše, régimen nazi | Croatia | 1941–1945 | [98][99][100] |

| 35,000 | Jadovno | NDH Ustaše, régimen nazi | Gospić, Croacia | Mayo–Agosto de 1941 | [cita requerida] |

| 12,790–75,000 | Stara Gradiška | NDH Ustaše, régimen nazi | Croatia | 1941–1945 | principalmente para mujeres y niños[101][102] |

| 13,171 | Camp Sumter | Estados Confederados de América | Andersonville (Georgia), EE.UU. | 1864–1865 | [103] |

| 12,000 | Crveni Krst | Régimen nazi, Serbia de Nedić | Niš, Serbia | 1941 | [104] |

| 12,000 | Gakovo | Yugoslavia | Norte de Serbia | 1944 | [105] |

| 9,000–10,000 | Omarska | Fuerzas bosnio serbias | Omarska, Bosnia y Herzegovina | 1992 | [106][107] |

| 2,963 | Cárcel de Elmira | Estados Unidos | Elmira (Nueva York), EE.UU. | 1864–1865 | [108] |

| 2,000 | Rab | Reino de Italia | Rab, Croacia | 1942 | [cita requerida] |

| >1,800 | Krugersdorp | Reino Unido | Krugersdorp, República de Transvaal | c 1900–1902 | Segunda guerra de los Bóers, principalmente para mujeres y niños[109] |

Hambrunas[editar]

Note: Some of these famines were partially caused by nature.

This section includes famines that were caused or exacerbated by the policies or actions of the ruling regime.

| Lowest estimate | Highest estimate | Event | Location | From | To | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 000 000 20 000 000[110] |

55 000 000[111] | Great Chinese Famine | People's Republic of China | 1958 | 1962 | During the Great Leap Forward under Mao Zedong tens of millions of Chinese starved to death[112] and about the same number of births were lost or postponed.[113] State violence during this period further exacerbated the death toll, and some 2.5 million people were beaten or tortured to death in connection with Great Leap policies.[114] |

| 6 000 000 | 8 000 000[51] | Soviet famine of 1932–1933, including Holodomor |

Soviet Union | 1932 | 1939 | A March 2008, Ukraine and nineteen other governments[52] have recognized the actions of the Soviet government that led to mass famine as an act of genocide. The joint statement at the United Nations in 2003 has defined the famine as the result of cruel actions and policies of the totalitarian regime that caused the deaths of millions of Ukrainians, Russians, Kazakhs and other nationalities in the USSR. On 23 October 2008 the European Parliament adopted a resolution[53] that recognized the Holodomor as a crime against humanity.[54]

On January 12, 2010, the court of appeals in Kiev opened hearings into the "fact of genocide-famine Holodomor in Ukraine in 1932–33", in May 2009 the Security Service of Ukraine had started a criminal case "in relation to the genocide in Ukraine in 1932–33".[55] In a ruling on January 13, 2010 the court found Stalin and other Bolshevik leaders guilty of genocide against the Ukrainians.[56] |

| 5 000 000[115] | 10 000 000[115] | Russian famine of 1921 | Soviet Russia | 1921 | 1922 | See also: Droughts and famines in Russia and the Soviet Union and Russian Civil War with its policy of War communism, especially prodrazvyorstka |

| 4 000 000 | 4 000 000 | Bengal famine of 1943 | British-ruled India | 1943 | 1943 | The Japanese conquest of Burma cut off India's main supply of rice imports[116]

However, administrative policies in British India ultimately helped cause the massive death toll.[117] |

| 1 000 000[118] | 1 000 000 | Siege of Leningrad | Soviet Union in World War II | 1941 | 1944 | An estimated 4 million Soviet people starved to death under Nazi occupation. There were an additional estimated 3 million famine deaths in areas of the USSR not under German occupation.[119] |

| 800,000[120] | 950,000[121] | Cambodian Genocide | Cambodia | 1975 | 1979 | An estimated 2 million Cambodians lost their lives to murder, forced labor and famine from the Cambodian Communist government, of which nearly half was caused by forced starvation. Came to an end due to invasion by Vietnam in 1979. |

| 750 000[122][123] | 1 500 000[124] | Great Irish Famine[125] | British-ruled Ireland | 1846 | 1849 | Although blight ravaged potato crops throughout Europe during the 1840s, the impact and human cost in Ireland—where a third of the population was significantly dependent on the Irish Lumper potato for food—was exacerbated by a host of political, social and economic factors which remain the subject of historical debate.[126][127] |

| 400 000[128] | 2 000 000[129] | Vietnamese Famine of 1945 | Vietnam | 1944 | 1945 | The Japanese occupation during World War II caused the famine in North Vietnam.[129] |

| 400 000[130] | 1 000 000[131] | 1983–85 famine in Ethiopia | Ethiopia | 1983 | 1985 | The famines that struck Ethiopia between 1961 and 1985, and in particular the one of 1983–5, were in large part created by government policies.[130] |

| 70 000[132] | 70 000 | Sudan famine | Sudán | 1998 | 1998 | The famine was caused almost entirely by human rights abuse and the war in Southern Sudan.[133] |

Inundaciones y deslizamientos de tierra[editar]

Nota: Estas inundaciones y deslizamientos de tierra fueron causados parcialmente por el hombre, por ejemplo la falla de represas, diques, rompeolas o muros de contención.

| Posición | Número de muertos | Evento | Lugar | Fecha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2,500,000–3,700,000[134] | Inundaciones de China de 1931 | China | 1931 |

| 2. | 900,000–2,000,000 | Inundación del río Amarillo de 1887 | China | 1887 |

| 3. | 500,000–700,000 | Inundación del río Amarillo de 1938 | China | 1938 |

| 4. | 26,000[135]-230,000[136] | Falla de 62 represas en la prefectura Zhumadian, Henan, la más grande de las cuales fue la de la Represa Banqiao, causada por el Tifón Nina. | China | Agosto de 1975 |

| 5. | 145,000 | Inundación de 1935 del río Yangtsé | China | 1935 |

| 6. | más de 100,000 | Inundación de San Félix, tormenta súbita | Holanda | 1530 |

| 7. | 100,000 | Inundación de Hanoi y el Delta del río Rojo | Vietnam del Norte | 1971 |

| 8. | 100,000 | Inundación de 1911 del río Yangtsé | China | 1911 |

| 9. | 50,000–80,000 | Inundación de Santa Lucía, tormenta súbita | Holanda, Inglaterra | 1287 |

| 10. | 10,000–50,000 | Tragedia de Vargas, deslizamiento | Venezuela | 1999 |

| 11. | 2,400 | Inundación de 1953 del Mar del Norte | Holanda, Escocia, Inglaterra, Bélgica | 31 de enero de 1953 |

Sacrificios humanos y suicidios rituales[editar]

Esta sección relaciona muertes de la sistemática práctica de sacrificio humano o suicidio. Para episodios notables individuales, véase Sacrificio humano y suicidio masivo.

| Estimado mínimo | Estimado máximo | Descripción | Group | Lugar | De | A | Notas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 000[cita requerida] | 1 500 000[cita requerida] | Sacrificio humano en la cultura Azteca | Aztecas | México | Siglo XIV | 1521 | Hasta 3 000 sacrificios anuales[137] |

| 13,000[138] | 13,100 | Sacrificio humano | Dinastía Shang | China | 1300 AC | 1050 AC | Últimos 250 años de dominación |

| 7941[139] | 7941 | Suicidios rituales | Sati | Bengala, India | 1815 | 1828 | |

| 3912 | 3912 | Pilotos suicidas kamikaze, ver nota[140] | Fuerza aérea imperial japonesa | Teatro del Pacífico | 1944 | 1945 | |

| 913 | 913 | Asesinato-suicidio de Jonestown | Seguidores de la secta del Templo del Pueblo | Jonestown | Noviembre 18, 1978 | Noviembre 19, 1978 | El acontecimiento fue la más grande pérdida en la vida civil estadounidense en un desastre no natural hasta los Ataques del 11 de septiembre de 2001. |

Otros acontecimientos mortales[editar]

Events with a large anthropogenic death toll not fitting any of the above classifications. May include deaths caused by famine, genocide, etc. as a portion of the total.

| Lowest estimate |

Highest estimate |

Event | Location | From | To | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49 000 000 | 78 000 000 | Mao Zedong era 1949–1976 | People's Republic of China | 1949 | 1976 | Millions of people died because of Mao Zedong's reforms,[141] mostly due to alleged human rights abuses and administration errors within China. Includes those who died during the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries, the Three-anti and Five-anti Campaigns, human rights abuses in Tibet, The Great Leap Forward (especially the resulting famine), and the Cultural Revolution.[142] See also Mass killings under communist regimes. |

| 8 000 000 | 61 000 000 | Soviet crimes 1917–1953 | Soviet Republics (1917–1922), the Soviet Union (1922–1953), the East and Center of Europe, Mongolia | 1917 | 1953 | Mass murders perpetrated by the Communist leaders of the Soviet Republics between 1917 and 1922 and later on in The Soviet Union during a period of 1922–1953 (until death of Joseph Stalin). It includes terror unleashed by Cheka during the Russian Civil War against nations and 'enemies of The Revolution',[143] deaths in Gulags,[144] forced resettlement,[145] Holodomor,[146] Dekulakization,[147] Great Purge,[148] National operations of the NKVD.[149] See also Mass killings under communist regimes. |

| 5 000 000[150] | 22 000 000[151] | Crimes during Congo Free State 1885-1908 | Now the Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1885 | 1908 | Private forces under the control of Leopold II of Belgium carried out mass murders, mutilations, and other crimes against the Congolese in order to encourage the gathering of valuable raw materials, principally rubber. Significant deaths also occurred due to major disease outbreaks and starvation, caused by population displacement and poor treatment.[152] Estimates of the death toll vary considerably because of the lack of a formal census before 1924, but a commonly cited figure of 10 million deaths was obtained by estimating a 50% decline in the total population during the Congo Free State and applying it to the total population of 10 million in 1924.[153] |

| 260,000[154] | 350,000[154] | Nanking Massacre | Nanking, China | 1937 | 1938 | The Nanking Massacre, commonly known as the Rape of Nanking, was a war crime committed by the Japanese military in Nanjing, then capital of the Republic of China, after it fell to the Imperial Japanese Army on 13 December 1937. |

| 100 000 | 2 000 000 | Indonesian killings of 1965–1966 | Indonesia | 1965 | 1966 | Massacres of people connected to the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) were carried out in 1965 and 1966. Death tolls are difficult to estimate.[155] |

| 100 000[156][157] | 250 000[158][159] | War in the Vendée | France | 1793 | 1796 | Described as genocide by some historians[157] but this claim has been widely discounted.[160] See also French Revolution |

| 100,000[161] | 120,000 | Manila Massacre | Manila, Philippines | 1945 | 1945 | During the Battle of Manila, at least 100,000 civilians were killed. |

| 75 000 | 170 000[162] | Sanctions against Iraq | Iraq | 1990 | 1998 | Sanctions imposed by the United Nations Security Council caused excess deaths of young children. |

| 50 000 | 80 000[163] | Operation Condor | South America | 1975 | 1983 | A campaign of political repression by right-wing dictatorships in South America, sponsored by the United States |

| 9000[164] | 30 000[165] | Dirty War | Argentina | 1976 | 1983 | At least 9,000 people were tortured and killed in Argentina from 1976 to 1983, carried out primarily by the Argentinean military Junta (part of Operation Condor). |

Véase también[editar]

Otras listas organizadas por número de muertos[editar]

- List of accidents and disasters by death toll

- List of battles and other violent events by death toll

- List of events named massacres

- List of genocides by death toll

- List of murderers by number of victims

- List of natural disasters by death toll

- List of ongoing conflicts

- List of Australian disaster by death toll

- List of Canadian disasters by death toll

- List of New Zealand disasters by death toll

- List of United Kingdom disasters by death toll

- List of United States disasters by death toll

Otraslistas con tópicos similares[editar]

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

- List of battles

- List of disasters

- List of earthquakes

- List of famines

- List of historic fires

- List of invasions

- List of massacres

- List of notable tropical cyclones

- List of riots

- List of terrorist incidents

- List of wars

- Lists of rail accidents

Tópicos relacionados[editar]

- Bajas de la Guerra de Irak

- Democidio

- Hambruna

- Genocidio

- Genocidio en la historia

- Enfermedad contagiosa

- Asesinato masivo

- Batallas más letales de la historia

- Bajas de guerra de los Estados Unidos

Referencias[editar]

- ↑ World population estimates

- ↑ David Wallechinsky (1 de septiembre de 1996). David Wallechinskys 20th Century: History With the Boring Parts Left Out. Little Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-92056-8.

- ↑ Brzezinski, Zbigniew: Out of Control: Global Turmoil on the Eve of the Twenty-first Century, Prentice Hall & IBD, 1994, ASIN B000O8PVJI – cited by White

- ↑ «BBC – History – Nuclear Power: The End of the War Against Japan». Bbc.co.uk. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ a b The Cambridge History of China: Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368, 1994, p.622, cited by White

- ↑ Alan Macfarlane (28 de mayo de 1997). The Savage Wars of Peace: England, Japan and the Malthusian Trap. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-18117-0.

- ↑ «Taiping Rebellion – Britannica Concise». Concise.britannica.com. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ «The Taiping Rebellion 1850-1871 Tai Ping Tian Guo». Taipingrebellion.com. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ Livre noir du Communisme: crimes, terreur, répression, page 468

- ↑ By Train to Shanghai: A Journey on the Trans-Siberian Railway By William J. Gingles page 259

- ↑ Jun 11, 2009 (11 de junio de 2009). «Asia Times Online :: China News, China Business News, Taiwan and Hong Kong News and Business». Atimes.com. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ «Emergence Of Modern China: II. The Taiping Rebellion, 1851–64».

- ↑ Willmott, 2003, p. 307

- ↑ 1918 Influenza: the Mother of All Pandemics, CDC

- ↑ a b «Timur Lenk (1369–1405)». Users.erols.com. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ Matthew's White's website (a compilation of scholarly estimates) -Miscellaneous Oriental Atrocities

- ↑ Matthew White (7 de noviembre de 2011). The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-08192-3.

- ↑ «Death toll figures of recorded wars in human history».

- ↑ Mike Davis (2001). Late Victorian Holocausts: El Ni鋘o Famines and the Making of the Third World. Verso Books. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-85984-739-8.

- ↑ Jacques Gernet (31 de mayo de 1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49712-1.

- ↑ «Russian Civil War». Spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ Bethany Lacina and Nils Petter Gleditsch, "Monitoring Trends in Global Combat: A New Dataset of Battle Deaths, European Journal of Population" (2005) 21: 145–166.

- ↑ "Congo war-driven crisis kills 45,000 a month-study" – Reuters, 22 Jan 2008.

- ↑ Charles Esdaile "Napoleon's Wars: An International History."

- ↑ «The Thirty Years War (1618–48)». Users.erols.com. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ a b «Mankind's Worst Wars and Armed Conflicts». Consultado el December 7, 2010.

- ↑ a b c d «Death Tolls for the Major Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century». Necrometrics.com. Consultado el September 24, 2012.

- ↑ a b Jan Wróbel, Odnaleźć przeszłość 1 (2002)«Odnaleźć przeszłość 1».

- ↑ a b Rummel, R.J., Statistics Of North Korean Democide: Estimates, Calculations, And Sources, Statistics of Democide, 1997.

- ↑ Charles Hirschman et al., "Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A New Estimate," Population and Development Review, December 1995.

- ↑ Shenon, Philip (23 April 1995). «20 Years After Victory, Vietnamese Communists Ponder How to Celebrate». The New York Times. Consultado el 24 February 2011.

- ↑ «Huguenot Religious Wars, Catholic vs. Huguenot (1562–1598)». Users.erols.com. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ «Shaka: Zulu Chieftain». Historynet.com. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ Sudan: Nearly 2 million dead as a result of the world's longest running civil war, U.S. Committee for Refugees, 2001. Archived 10 December 2004 on the Internet Archive. Accessed 10 April 2007

- ↑ John Shertzer Hittell, "A Brief History of Culture" (1874) p.137: "In the two centuries of this warfare one million persons had been slain..." cited by White

- ↑ Robertson, John M., "A Short History of Christianity" (1902) p.278. Cited by White

- ↑ a b Buchenau, Jürgen (2005). Mexico otherwise: modern Mexico in the eyes of foreign observers. UNM Press. p. 285. ISBN 0-8263-2313-8.

- ↑ «The Iran-Iraq War». Jewish Virtual Library. Consultado el 15 October 2010.

- ↑ Roger Hardy (22 September 2005). «The Iran-Iraq War: 25 years on». BBC News. Consultado el 15 October 2010.

- ↑ Jurg Meister, Francisco Solano López Nationalheld oder Kriegsverbrecher?, Osnabrück: Biblio Verlag, 1987. 345, 355, 454–5

- ↑ Another estimate is that from the pre-war population of 1,337,437, the population fell to 221,709 (28,746 men, 106,254 women, 86,079 children) by the end of the war (War and the Breed, David Starr Jordan, p. 164. Boston, 1915; Applied Genetics, Paul Popenoe, The Macmillan Company, New York, 1918)

- ↑ «Reitlinger, The Final Solution (1953) cited by White». Necrometrics.com. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ a b Donald L. Niewyk; Francis R. Nicosia (2000). The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. Columbia University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-231-11200-0.

- ↑ http://frank.mtsu.edu/~baustin/holo.html

- ↑ http://www2.sptimes.com/Holocaust_museum/11_million.html

- ↑ cited in Re. Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation (Swiss Banks) Special Master's Proposals, September 11, 2000.

- ↑ Horst von Buttlar: Forscher öffnen Inventar des Schreckens at Spiegel Online (1 October 2003) (German)

- ↑ Jacques Vallin, France Mesle, Serguei Adamets, Serhii Pyrozhkov, A New Estimate of Ukrainian Population Losses during the Crises of the 1930s and 1940s, Population Studies, Vol. 56, No. 3. (Nov. 2002), pp. 249–264

- ↑ France Meslé, Gilles Pison, Jacques Vallin France-Ukraine: Demographic Twins Separated by History, Population and societies, N°413, juin 2005

- ↑ France Meslé; Jacques Vallin (2003). Mortalité et causes de décès en Ukraine au XXe siècle: la crise sanitaire dans les pays de l'ex-URSS. Ined. ISBN 978-2-7332-0152-7.

- ↑ a b – "The famine of 1932–33", Encyclopædia Britannica. Quote: "The Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–33—a man-made demographic catastrophe unprecedented in peacetime. Of the estimated six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union, about four to five million were Ukrainians... Its deliberate nature is underscored by the fact that no physical basis for famine existed in Ukraine... Soviet authorities set requisition quotas for Ukraine at an impossibly high level. Brigades of special agents were dispatched to Ukraine to assist in procurement, and homes were routinely searched and foodstuffs confiscated... The rural population was left with insufficient food to feed itself." Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «britannica» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ a b sources differ on interpreting various statements from different branches of different governments as to whether they amount to the official recognition of the famine as genocide by the country. For example, after the statement issued by the Latvian Sejm on March 13, 2008, the total number of countries is given as 19 (according to Ukrainian BBC: "Латвія визнала Голодомор ґеноцидом"), 16 (according to Korrespondent, Russian edition: "После продолжительных дебатов Сейм Латвии признал Голодомор геноцидом украинцев"), "more than 10" (according to Korrespondent, Ukrainian edition: "Латвія визнала Голодомор 1932–33 рр. геноцидом українців")

- ↑ a b cs - čeština. «European Parliament resolution on the commemoration of the Holodomor, the Ukraine artificial famine (1932–1933)». Europarl.europa.eu. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ a b European Parliament recognises Ukrainian famine of 1930s as crime against humanity (Press Release 23-10-2008)

- ↑ a b Holodomor court hearings begin in Ukraine, Kyiv Post (January 12, 2010)

- ↑ a b Yushchenko brings Stalin to court over genocide, RT (January 14, 2010)

- ↑ Rummel, R.J. Death by Government, Chapter 3: Pre-Twentieth Century Democide

- ↑ Stannard, David E. (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0. «In the 1940s and 1950s conventional wisdom held that the population of the entire hemisphere in 1492 was little more than 8,000,000—with fewer than 1,000,000 people living in the region north of present-day Mexico. Today, few serious students of the subject would put the hemispheric figure at less than 75,000,000 to 100,000,000 (with approximately 8,000,000 to 12,000,000 north of Mexico).»

- ↑ Cook, Noble David (1998). Born to die: disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ «The Story of... Smallpox». Pbs.org. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ Koplow, David A. (2003). «Smallpox The Fight to Eradicate a Global Scourge». University of California Press. Consultado el 22 de febrero de 2009.

- ↑ Arthur C. Aufderheide; Conrado Rodriguez-Martin (13 de mayo de 1998). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Paleopathology. Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-521-55203-5.

- ↑ Cook, Noble David (1998). Born to die: disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 9.

- ↑ Stafford Poole, quoted in Royal, p. 63.

- ↑ a b Heuveline, Patrick (2001). "The Demographic Analysis of Mortality in Cambodia." In Forced Migration and Mortality, eds. Holly E. Reed and Charles B. Keely. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- ↑ Staff, Senior Khmer Rouge leader charged, BBC 19 September 2007

- ↑ Seth Mydans, Khmer Rouge Leaders Indicted

- ↑ a b Stannard, David. American Holocaust. Oxford University Press, 1993

- ↑ Dora Apel (1 de julio de 2002). Memory Effects: The Holocaust and the Art of Secondary Witnessing. Rutgers University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8135-3049-9.

- ↑ «Lewis. Race and Slavery in the Middle East. Oxford Univ Press 1994.». Fordham.edu. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ Willem Adriaan Veenhoven; Winifred Crum Ewing, Stichting Plurale Samenlevingen (1975). Case Studies on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms: A World Survey. BRILL. p. 440. ISBN 978-90-247-1779-8.

- ↑ a b See, e.g., Rwanda: How the genocide happened, BBC, April 1, 2004, which gives an estimate of 800,000, and OAU sets inquiry into Rwanda genocide, Africa Recovery, Vol. 12 1#1 (August 1998), page 4, which estimates the number at between 500,000 and 1,000,000. 7 out of 10 Tutsis were killed.

- ↑ Christoph Bergner, Secretary of State in Germany's Bureau for Inner Affairs, Deutschlandfunk, November 29, 2006,[1]

- ↑ Hermann Kinder; Werner Hilgemann (1978). The Anchor atlas of world history. Anchor Books. p. 221.

- ↑ a b Jürgen Weber (2004). Germany, 1945–1990: A Parallel History. p. 2. ISBN 978-963-9241-70-1.

- ↑ a b Arie Marcelo Kacowicz, Pawel Lutomski, Population resettlement in international conflicts: a comparative study, Lexington Books, 2007, p.100, ISBN 073911607: "...largest movement of European people in modern history" [2]

- ↑ Peter H. Schuck; Rainer Münz (1 de diciembre de 2001). Paths to Inclusion: The Integration of Migrants in the United States and Germany. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-57181-092-2.

- ↑ *Expelling the Germans: British Opinion and Post-1945 Population Transfer in Context, Matthew Frank Oxford University Press, 2008

- Europe and German unification,

- ↑ *Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and international agreements. Routledge. p. 656. ISBN 0-415-93924-0.

- Naimark, Norman M. (2001). Fires of hatred: ethnic cleansing in twentieth-century Europe. Harvard University Press. pp. 15, 112. 121, 136. ISBN 0-674-00994-0.

- Curp, T. David (2006). A clean sweep?: the politics of ethnic cleansing in western Poland, 1945–1960. University of Rochester Press. p. 200. ISBN 1-58046-238-3.

- Cordell, Karl (1999). Ethnicity and democratisation in the new Europe. Routledge. p. 175. ISBN 0-415-17312-4.

- Diner, Dan; Gross, Raphael; Weiss, Yfaat (2006). Jüdische Geschichte als allgemeine Geschichte. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 163. ISBN 3-525-36288-9.

- Gibney, Matthew J. (2005). Immigration and asylum: from 1900 to the present, Volume 3. ABC-CLIO. p. 196. ISBN 1-57607-796-9.

- Glassheim, Eagle (2001). Ther, Philipp; Siljak, Ana, eds. Redrawing nations: ethnic cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944–1948. Harvard Cold War studies book series. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 197. ISBN 0-7425-1094-8.

- Shaw, Martin (2007). What is genocide?. Polity. p. 56. ISBN 0-7456-3182-7.

- Totten, Paul; Bartrop; Jacobs, Steven L (2008). Dictionary of genocide, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 335. ISBN 0-313-34644-5.

- Frank, Matthew James (2008). Expelling the Germans: British opinion and post-1945 population transfer in context. Oxford historical monographs. Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-19-923364-0.

- ↑

- Shaw, Martin (2007). What is genocide?. Polity. ISBN 0-7456-3182-7. pp. 56,60,61

- Rubinstein, W.D. (2004). Genocide, a history. Pearson Education Ltd. p. 260. ISBN 0-582-50601-8.

- ↑ European Court of Human Rights – Jorgic v. Germany Judgment, July 12, 2007. § 47

- ↑ Jescheck, Hans-Heinrich (1995). Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-14280-0.

- ↑ Ermacora, Felix (1991). «Gutachten Ermacora 1991» (PDF).

- ↑ Kamuran Gürün: Ermeni Soykirmi. 3rd Volume, Ankara 1985, p. 227

- ↑ French in Armenia 'massacre' row BBC

- ↑ a b Henry Morgenthau, Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, Doubleday, Page & Company, Garden City, New York, 1919.

- ↑ a b Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

- ↑ a b Rzeź wołyńska (pl)

- ↑ a b While the official Pakistani government report estimated that the Pakistani army was responsible for 26,000 killings in total, other sources have proposed various estimates ranging between 200,000 and 3 million. Indian Professor Sarmila Bose recently expressed the view that a truly impartial study has never been done, while Bangladeshi ambassador Shamsher M. Chowdhury has suggested that a joint Pakistan-Bangladeshi commission be formed to properly investigate the event.

Chowdury, Bose comments – Dawn Newspapers Online.

Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report, chapter 2, paragraph 33 (official 1974 Pakistani report).White, Matthew. «Death Tolls for the Major Wars and Atrocities of the 20th Century: Bangladesh». Users.erols.com. «History: The Bangali Genocide, 1971». Virtualbangladesh.com. - ↑ Wellers, Georges. Essai de determination du nombre de morts au camp d'Auschwitz (attempt to determine the number of dead at the Auschwitz camp), Le Monde Juif, Oct–Dec 1983, pp. 127–159

- ↑ Brian Harmon, John Drobnicki, Historical sources and the Auschwitz death toll estimates

- ↑ «Operation Reinhard: Treblinka Deportations». Nizkor.org. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Americana

- ↑ Peter Witte and Stephen Tyas, A New Document on the Deportation and Murder of Jews during "Einsatz Reinhardt" 1942, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Vol. 15, No. 3, Winter 2001, ISBN 0-19-922506-0

- ↑ Raul Hilberg (2003). The Destruction of the European Jews: Third Edition. ISBN 978-0-300-09557-9.

- ↑ Yitzhak Arad, Bełżec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1987, NCR 0-253-34293-7

- ↑ Ludwik Kowalski: Alaska notes on Stalinism Retrieved 18 January 2007. Case Study: Stalin's Purges from Genderside Watch. Retrieved 19 January 2007. George Bien, Gulag Survivor in the Boston Globe, June 22, 2005, Kolyma

- ↑ «Jewish virtual library». Jewish virtual library. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ «Croatian holocaust still stirs controversy». BBC News. 29 de noviembre de 2001. Consultado el 29 de septiembre de 2010.

- ↑ «Balkan 'Auschwitz' haunts Croatia». BBC News. 25 de abril de 2005. Consultado el 29 de septiembre de 2010. «No one really knows how many died here. Serbs talk of 700,000. Most estimates put the figure nearer 100,000.»

- ↑ Jelka Smreka. «STARA GRADIŠKA Ustaški koncentracijski logor». Spomen područja Jasenovac. Consultado el 25 de agosto de 2010.

- ↑ Davor Kovačić (2004). «Iskapanja na prostoru koncentracijskog logora Stara Gradiška i procjena broj žrtava». Consultado el 25 de agosto de 2010.

- ↑ The Andersonville Prison Trial: The Trial of Captain Henry Wirz, by General N.P. Chipman, 1911.

- ↑ «On the killing of Roma in World War II». Mrc.org.rs. 13 de marzo de 2013. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ Razprave in gradivo, Volume 55. Institut za Narodnostna Vprašanja. 2008.

- ↑ «The Unindicted: Reaping the Rewards of "Ethnic Cleansing" in Prijedor». Human Rights Watch. 1 de enero de 1997.

- ↑ «Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team report».

- ↑ Horigan, Michael (2002). Death Camp of the North: The Elmira Civil War Prison Camp. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-1432-2.

- ↑ Walker, DR (20 de septiembre de 2011). «Burgershoop cemetery and concentration camp in Krugersdorp.». The All at Sea Network. Consultado el 21 de diciembre de 2011.

- ↑ Stéphane Courtois; Mark Kramer (15 de octubre de 1999). Livre Noir Du Communisme: Crimes, Terreur, Répression. ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2.

- ↑ Wemheuer, Felix (July 2011). «Sites of horror: Mao's Great Famine [with response]». The China Journal (66): 155-164. JSTOR 41262812. on p.163 Frank Dikötter, in his response, quotes Yu Xiguang's figure of 55 million

- ↑ Becker, Jasper (1998). Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine. Holt Paperbacks p.xi.

- ↑ "China's great famine: 40 years later". British Medical Journal 1999;319:1619–1621 (18 December)

- ↑ Dikötter, Frank. Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–62. Walker & Company, 2010. p. 298.

- ↑ a b "How the U.S. saved a starving Soviet Russia: PBS film highlights Stanford scholar's research on the 1921–23 famine". Stanford University. April 4, 2011.

- ↑ Nicholas Tarling (Ed.) The Cambridge History of SouthEast Asia Vol.II Part 1 pp139-40

- ↑ Madhusree Mukerjee, Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India During World War II. See also Book review: Churchill's secret war in India by Susannah York

- ↑ "Last Battle of Siege of Leningrad Re-Enacted." The St. Petersburg Times. January 29, 2008.

- ↑ The Russian Academy of Science Rossiiskaia Akademiia nauk. Liudskie poteri SSSR v period vtoroi mirovoi voiny:sbornik statei. Sankt-Peterburg 1995 ISBN 5-86789-023-6

- ↑ Bruce Sharp (2008), Counting Hell 2.Ben Kiernan, paragraph 3. Mekong.

- ↑ Marek Sliwinski (1995), Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: Une Analyse Démographique, L'Harmattan, p. 82.

- ↑ Foster, R.F. 'Modern Ireland 1600–1972'. Penguin Press, 1988. p324. Foster's footnote reads: "Based on hitherto unpublished work by C. Ó Gráda and Phelim Hughes, 'Fertility trends, excess mortality and the Great Irish Famine'...Also see C.Ó Gráda and Joel Mokyr, 'New developments in Irish Population History 1700–1850', Economic History Review, vol. xxxvii, no.4 (November 1984), pp. 473–488."

- ↑ Joseph Lee, The Modernisation of Irish Society p. 1. Lee says 'at least 800,000'.

- ↑ Vaughan, W.E. and Fitzpatrick, A.J.(eds). Irish Historical Statistics, Population, 1821/1971. Royal Irish Academy, 1978

- ↑ The Great Irish Famine Approved by the New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education on 10 September 1996, for inclusion in the Holocaust and Genocide Curriculum at the secondary level. Revision submitted 11/26/98.

- ↑ Cecil Woodham-Smith (1991). The great hunger: Ireland 1845–1849. Penguin Books. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-14-014515-1.

- ↑ Dr Christine Kinealy (2006). This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine, 1845–52. ISBN 978-0-7171-4011-4.

- ↑ Charles Hirschman et al. "Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A New Estimate". Population and Development Review (December 1995).

- ↑ a b Koh, David (21 August 2008). «Vietnam needs to remember famine of 1945». The Straits Times (Singapore). Consultado el 25 January 2010.

- ↑ a b de Waal, Alex (2002) [1997]. Famine Crimes: Politics & the Disaster Relief Industry in Africa. Oxford: James Currey. ISBN 0-85255-810-4.

- ↑ "Flashback 1984: Portrait of a famine". BBC News. April 6, 2000.

- ↑ Ó Gráda, Cormac (2009), Famine: a short history, Princeton University Press, p. 24, ISBN 978-0-691-12237-3..

- ↑ Despite aid effort, Sudan famine squeezing life from dozens daily CNN, Accessed May 25, 2006

- ↑ «Worst Natural Disasters In History». Nbc10.com. Consultado el 11 de agosto de 2010.

- ↑ Dai Qing (1998). The River Dragon Has Come!: The Three Gorges Dam and the Fate of China's Yangtze River and Its People. M.E. Sharpe. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-7656-0206-0.

- ↑ 230,000 is the highest of a range of unofficial estimates, including also deaths of ensuing epidemics and famine, in Yi, 1998

- ↑ "The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice", by Michael Harner. Natural History, April 1977, Vol. 86, No. 4, pages 46–51.

- ↑ National Geographic, July 2003, cited by White

- ↑ Sakuntala Narasimhan, Sati: widow burning in India, quoted by Matthew White, "Selected Death Tolls for Wars, Massacres and Atrocities Before the 20th Century", p.2 (July 2005), Historical Atlas of the 20th Century (self-published, 1998–2005).

- ↑ This toll is only for the number of Japanese pilots killed in Kamikaze suicide missions. It does not include the number of enemy combatants killed by such missions, which is estimated to be around 4,000. Kamikaze pilots are estimated to have sunk or damaged beyond repair some 70 to 80 allied ships, representing about 80% of allied shipping losses in the final phase of the war in the Pacific (see Kamikaze).

- ↑ «Did Mao Really Kill Millions in the Great Leap Forward?». Maoists.org. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ http://www.scaruffi.com/politics/dictat.html

- ↑ Andrew and Mitrokhin, The Sword and the Shield, paperback ed., Basic books, 1999.

- ↑ Steven Rosefielde (15 de febrero de 2010). Red Holocaust. Taylor & Francis. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-415-77757-5.

- ↑ Павел Полян, Не по своей воле... (Pavel Polian, Against Their Will... A History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR), ОГИ Мемориал, Moscow, 2001

- ↑ С. Уиткрофт (Stephen G. Wheatcroft), "О демографических свидетельствах трагедии советской деревни в 1931—1933 гг.

- ↑ Lynne Viola The Unknown Gulag. The Lost World of Stalin's Special Settlements Oxford University Press 2007,

- ↑ Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments by Michael Ellman, 2002

- ↑ Vadim Rogovin "The Party of the Executed"

- ↑ Forbath, Peter. The River Congo: The Discovery, Exploration, and Exploitation of the World's Most Dramatic River, 1991 (Paperback). Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-122490-1.

- ↑ R. J. Rummel Exemplifying the Horror of European Colonization:Leopold's Congo"

- ↑ p.226-232, Hochschild, Adam (1999), King Leopold's Ghost, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 0-547-52573-7

- ↑ Hochschild p.226–232.

- ↑ a b Iris Chang; Iris Chang (1997). The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II. Basic Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7867-2760-5.

- ↑ Cribb, Robert (2002). «Unresolved Problems in the Indonesian Killings of 1965–1966». Asian Survey 42 (4): 550-563. doi:10.1525/as.2002.42.4.550.

- ↑ Donald Greer, The Terror, a Statistical Interpretation, Cambridge (1935)

- ↑ a b Reynald Secher, La Vendée-Vengé, le Génocide franco-français (1986)

- ↑ Jean-Clément Martin, La Vendée et la France, Éditions du Seuil, collection Points, 1987 he gives the highest estimate of the civil war, including republican losses and premature death. However, he does not consider it as a genocide.

- ↑ Jacques Hussenet (dir.), « Détruisez la Vendée ! » Regards croisés sur les victimes et destructions de la guerre de Vendée, La Roche-sur-Yon, Centre vendéen de recherches historiques, 2007, p.148.

- ↑ Gough, Hugh (December de 1987). «Genocide and the Bicentenary: The French Revolution and the Revenge of the Vendee». The Historical Journal 30 (4). JSTOR 2639130.

- ↑ White, Matthew. «Death Tolls for the Man-made Megadeaths of the 20th Century». Users.erols.com.

- ↑ Garfield, Richard (1999). Morbidity and Mortality Among Iraqi Children from 1990 Through 1998: Assessing the Impact of the Gulf War and Economic Sanctions. Consultado el 9 July 2013.

- ↑ «Background on Chile». The Center for Justice & Accountability. Consultado el 9 July 2013.

- ↑ Phil Gunson. «The Guardian, Thursday 2 April 2009». Guardian. Consultado el 23 de agosto de 2013.

- ↑ PBS News Hour, 16 Oct. 1997, et al. Argentina Death Toll, Twentieth Century Atlas

Enlaces externos[editar]

- Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II

- Top 100 aviation disasters on AirDisaster.com

Elizabeth Hurley lució un Versace negro, frecuentemente referenciado como "AQUEL vestido" (en inglés, THAT dress),[1][2] cuando acompañó a Hugh Grant al estreno de Cuatro bodas y un funeral en 1994. El vestido estaba sostenido por varios imperdibles de oro de gran tamaño.[3][4] El traje es quizá la creación más conocida de Versace,[5] y es ampliamente considerado el responsable de lanzar a Hurley a la escena global.[3]

El ceñido vestido largo negro fue hecho de piezas de seda y lycra, con imperdibles de oro de gran tamaño ubicados en "sitios estratégicos".[6] El traje tenía una amplia abertura frontal desde el cuello a más abajo de los pechos, con escote en pico y dos tirantes delgados en cada hombro, también con aberturas laterales en el cuerpo sujetas cada una por seis grandes imperdibles dorados. Otro imperdible más adornaba la abertura lateral de la falda hasta la cima del muslo. Se dice que el vestido estuvo inspirado en el punk, "neo-punk",[5] y algo que "surgió del desarrollo del sari", de acuerdo con Gianni Versace.[2][7]

Diseño[editar]

Controversia[editar]

Hurley dijo del traje que "Ese traje fue un favor de Versace porque yo no podía comprarlo. Su gente me dijo que no tenían traje de noche, pero quedaba una prenda en la oficina de prensa. Entonces me lo puse y listo."[8] Sin embargo, a algunos el traje les pareció demasiado indecente, revelador y de mal gusto.[9][10] En respuesta a los comentarios sobre la naturaleza reveladora del vestido, Hurley dijo que "A diferencia de muchos diseñadores, Versace diseña ropa para celebrar la forma femenina en vez de eliminarla". Sin embargo, en 2018 la actriz declaró que el vestido "no era para tanto".[11][12]

El vestido negro fue hecho de piezas de seda y lycra, con imperdibles de oro de gran tamaño ubicados en "sitios estratégicos".[6] El traje tenía una amplia apertura en el frente, desde el cuello hasta al menos la mitad de los pechos, con dos tiras delgadas en los hombros, cada lado conectado por un imperdible de oro y dos partes cortadas de ambos lados que se sostenían unidas con seis imperdibles en cada lado y uno en la parte superior del corte en cada lado conectándolo con la parte de los pechos. Se dice que el vestido estuvo inspirado en el punk, "neo-punk",[5] y algo que "surgió del desarrollo sari", de acuerdo con Gianni Versace.[2][7]

El vestido inició la tendencia cada vez más habitual entre actrices y cantantes de lucir diseños muy atrevidos en presentaciones y eventos, incluso siendo superado por otros modelos de la década de 2010. El Versace negro fue de nuevo vestido por Lady Gaga en 2012 durante un evento en Italia,[13] y una adaptación del mismo por Jennifer Lawrence en 2018,[14] por el que tuvo críticas por utilizarlo durante un frío día invernal al aire libre.[15]

Controversia[editar]

Hurley dijo del traje que "Ese traje fue un favor de Versace porque yo no podía comprarlo. Su gente me dijo que no tenían traje de noche, pero quedaba una prenda en la oficina de prensa. Entonces me lo puse y listo."[8] Sin embargo, a algunos el traje les pareció demasiado indecente, revelador y de mal gusto.[9][10] En respuesta a los comentarios sobre la naturaleza reveladora del vestido, Hurley dijo que "A diferencia de muchos diseñadores, Versace diseña ropa para celebrar la forma femenina en vez de eliminarla."

- ↑ Grant, Kimberly (September 2002). Miami and the Keys. Lonely Planet. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-74059-183-6. Consultado el 1 de mayo de 2011.

- ↑ a b c Pedersen, Stephanie (30 November 2004). Bra: a thousand years of style, support and seduction. David & Charles. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7153-2067-9. Consultado el 1 de mayo de 2011.

- ↑ a b Urmee Khan (9 October 2008). «Liz Hurley 'safety pin' dress voted the greatest dress». The Telegraph. Consultado el 1 de mayo de 2011.

- ↑ Waxler, Caroline (2004). Stocking up on sin: how to crush the market with vice-based investing. John Wiley and Sons. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-471-46513-3. Consultado el 1 de mayo de 2011.

- ↑ a b c White, Nicola; Griffiths, Ian (2000). The fashion business: theory, practice, image. Berg Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-85973-359-2. Consultado el 1 de mayo de 2011. Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «WhiteGriffiths2000» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ a b McRobbie, Angela (26 de junio de 1998). British fashion design: rag trade or image industry?. Routledge. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-415-05781-3. Consultado el 1 de mayo de 2011. Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «McRobbie1998» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ a b Martin, Richard Harrison; Versace, Gianni (diciembre de 1997). Gianni Versace. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-842-3. Consultado el 1 de mayo de 2011. Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «MartinVersace1997» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ a b Steer, Deirdre Clancy (abril de 2009). The 1980s and 1990s. Infobase Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-60413-386-8. Consultado el 1 de mayo de 2011. Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «Steer2009» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ a b D'Epiro, Peter; Pinkowish, Mary Desmond (2 de octubre de 2001). Sprezzatura: 50 ways Italian genius shaped the world. Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0-385-72019-9. Consultado el 1 de mayo de 2011. Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «D'EpiroPinkowish2001» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ a b Bruzzi, Stella; Gibson, Pamela Church (2000). Fashion cultures: theories, explorations, and analysis. Routledge. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-415-20685-3. Consultado el 1 de mayo de 2011. Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «BruzziGibson2000» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ «Lo que opina Elizabeth Hurley hoy sobre EL vestido de Versace». Harper's BAZAAR. 13 de junio de 2018. Consultado el 28 de agosto de 2018.

- ↑ Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; no se ha definido el contenido de las referencias llamadas:0 - ↑ «Liz Hurley y el vestido de Versace que revolucionó la alfombra roja». 8 de octubre de 2016.

- ↑ «Jennifer Lawrence reinterpreta el icónico look de Versace de Liz Hurley 24 años después». HOLA USA. 21 de febrero de 2018. Consultado el 28 de agosto de 2018.

- ↑ «Jennifer Lawrence responde a las críticas sobre su vestido negro de Versace». Glamour. 21 de febrero de 2018. Consultado el 28 de agosto de 2018.