Diferencia entre revisiones de «Río Misuri»

Sin resumen de edición |

Sin resumen de edición |

||

| Línea 23: | Línea 23: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

El '''río Misuri''' o '''río Missouri ''' ({{lang-en|Missouri River}}) es el río más largo de América del Norte,<ref name="RiversWorld">{{cite web|author=Howard Perlman, USGS |url=http://ga.water.usgs.gov/edu/riversofworld.html |title=Lengths of major rivers, from USGS Water-Science School |publisher=Ga.water.usgs.gov |date=2012-10-31 |accessdate=2012-11-21}}</ref> el [[Anexo:Ríos de Estados Unidos| afluente más largo en los Estados Unidos]] y una de las principales vías navegables del centro de los [[Estados Unidos]]. Nace en las [[montañas Rocosas]] en el oeste de [[Montana]] —de la confluencia de tres ríos, [[Río Jefferson|Jefferson]], [[Río Madison|Madison]] y [[Río Gallatin|Gallatin]]— y fluye hacia el este y el sur durante {{unidad|3767|km}}<ref name="modifications"/>, atravesando las [[Grandes Llanuras]] del este de [[Montana]], [[Dakota del Norte]] y [[Dakota del Sur]], marcando la frontera entre [[Nebraska]] e [[Iowa]], y después entre [[Kansas]] y [[Misuri]], hasta desaguar en el [[río Misisipi]] al norte de la ciudad de [[St. Louis (Misuri)|St. Louis]], [[Misuri (estado)|Misuri]]. El río drena una cuenca poco poblada y de [[clima semiárido]] de más de {{unidad|1300000|km²}}, aproximadamente una venteava parte del subcontinente [[América del Norte|norteamericano]], y que incluye partes de los diez estados de los Estados Unidos y de dos provincias canadienses. Cuando se considera con la parte baja del río Misisipí, el sistema Misisipi–Misuri llega a los {{unidad|6275|km}} —el [[Anexo:Ríos más largos del mundo|cuarto sistema fluvial más largo del mundo]]<ref name="RiversWorld" />—y drena una cuenca de {{unidad|2980000|km²}} —la [[Anexo:Cuencas del mundo por |

El '''río Misuri''' o '''río Missouri ''' ({{lang-en|Missouri River}}) es el río más largo de América del Norte,<ref name="RiversWorld">{{cite web|author=Howard Perlman, USGS |url=http://ga.water.usgs.gov/edu/riversofworld.html |title=Lengths of major rivers, from USGS Water-Science School |publisher=Ga.water.usgs.gov |date=2012-10-31 |accessdate=2012-11-21}}</ref> el [[Anexo:Ríos de Estados Unidos| afluente más largo en los Estados Unidos]] y una de las principales vías navegables del centro de los [[Estados Unidos]]. Nace en las [[montañas Rocosas]] en el oeste de [[Montana]] —de la confluencia de tres ríos, [[Río Jefferson|Jefferson]], [[Río Madison|Madison]] y [[Río Gallatin|Gallatin]]— y fluye hacia el este y el sur durante {{unidad|3767|km}}<ref name="modifications"/>, atravesando las [[Grandes Llanuras]] del este de [[Montana]], [[Dakota del Norte]] y [[Dakota del Sur]], marcando la frontera entre [[Nebraska]] e [[Iowa]], y después entre [[Kansas]] y [[Misuri]], hasta desaguar en el [[río Misisipi]] al norte de la ciudad de [[St. Louis (Misuri)|St. Louis]], [[Misuri (estado)|Misuri]]. El río drena una cuenca poco poblada y de [[clima semiárido]] de más de {{unidad|1300000|km²}}, aproximadamente una venteava parte del subcontinente [[América del Norte|norteamericano]], y que incluye partes de los diez estados de los Estados Unidos y de dos provincias canadienses. Cuando se considera con la parte baja del río Misisipí, el sistema Misisipi–Misuri llega a los {{unidad|6275|km}} —el [[Anexo:Ríos más largos del mundo|cuarto sistema fluvial más largo del mundo]]<ref name="RiversWorld" />—y drena una cuenca de {{unidad|2980000|km²}} —la [[Anexo:Cuencas del mundo por superficie|sexta mayor del mundo]]. |

||

Desde hace más de |

Desde hace más de {{unidad|12000|años}}, muchas personas han dependido del Misuri y sus afluentes como una fuente de sustento y transporte. Más de diez grandes grupos de [[nativos americanos]] poblaron la cuenca, la mayoría con un estilo de vida nómada y que dependía de las enormes manadas de [[bisonte]]s que una vez vagaron a través de las Grandes Llanuras. Los primeros europeos encontraron el río a finales del siglo XVII —fue descubierto por el explorador francés [[Étienne de Veniard]]—, y la región pasó por manos españolas y francesas antes de convertirse en parte de los Estados Unidos a través de la [[compra de la Luisiana]]. El Misuri se creyó durante mucho tiempo que podría ser parte del [[Paso del Noroeste]] —una vía de agua desde el Atlántico hasta el Pacífico—, pero cuando la [[expedición de Lewis y Clark]] logró recorrer por vez primera toda la longitud del río, se confirmó que esa mítica vía no era más que una leyenda. |

||

El Misuri fue una de las principales vías para la expansión hacia el Oeste de los Estados Unidos durante el siglo XIX. El crecimiento del comercio de la piel a principios de 1800 causó que los tramperos exploraran la región y abrieran caminos. Los [[Pioneros del oeste estadounidense|pioneros]] se dirigieron al Oeste en masa a partir de la década de 1830, primero en [[carromato]]s, y luego en el creciente número de barcos de vapor que entraron en explotación en el río. Los antiguas tierras de los nativos en la cuenca fueron tomadas por los colonos, lo que llevó a algunas de las guerras más largas y violentas contra los pueblos indígenas en la historia estadounidense. |

El Misuri fue una de las principales vías para la expansión hacia el Oeste de los Estados Unidos durante el siglo XIX. El crecimiento del comercio de la piel a principios de 1800 causó que los tramperos exploraran la región y abrieran caminos. Los [[Pioneros del oeste estadounidense|pioneros]] se dirigieron al Oeste en masa a partir de la década de 1830, primero en [[carromato]]s, y luego en el creciente número de barcos de vapor que entraron en explotación en el río. Los antiguas tierras de los nativos en la cuenca fueron tomadas por los colonos, lo que llevó a algunas de las guerras más largas y violentas contra los pueblos indígenas en la historia estadounidense. |

||

| Línea 41: | Línea 41: | ||

Fluyendo hacia el este a través de las llanuras del este de Montana, el Misuri recibe el [[río Poplar]] desde el norte antes de cruzar a [[Dakota del Norte]], donde el [[río Yellowstone]], su mayor afluente por caudal, se le une desde el suroeste. En la confluencia, el Yellowstone es en realidad el río más grande.{{#tag:ref|The Missouri's flow at [[Culbertson, Montana]], {{convert|25|mi|km|abbr=on}} above the confluence of the two rivers, is about {{convert|9820|cuft/s|m3/s|abbr=on}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2010/pdfs/06185500.2010.pdf|title=USGS Gage #06185500 on the Missouri River near Culbertson, MT|publisher=U.S. Geological Survey|work=National Water Information System|date=1941–2010|accessdate=2011-07-04}}</ref> and the Yellowstone's discharge at [[Sidney, Montana]], roughly the same distance upstream along that river, is about {{convert|12370|cuft/s|m3/s|abbr=on}}.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2010/pdfs/06329500.2010.pdf|title=USGS Gage #06329000 on the Yellowstone River near Sidney, MT|publisher=U.S. Geological Survey|work=National Water Information System|date=1911–2010|accessdate=2011-07-04}}</ref>|group=n}} El Misuri serpentea luego al este más allá de [[Williston (Dakota del Norte)|Williston]] y en el [[lago Sakakawea]], el embalse formado por la [[presa Garrison]]. Aguas abajo de la presa, el río Misuri recibe al [[río Knife]] desde el oeste y fluye hacia el sur hasta [[Bismarck(Dakota del Norte)|Bismarck]], la capital de Dakota del Norte, donde el río se le une el [[río Heart (Dakota del Norte)|río Heart]], que le aborda desde el oeste. Se ralentiza en el embalse del [[lago Oahe]] justo antes de la confluencia del [[río Cannonball]]. Mientras continúa hacia el sur, finalmente llega a la [[presa Oahe]], en [[Dakota del Sur]], donde se le unen los ríos [[río Grand (Dakota del Sur)|Grand]], [[río Moreau|Moreau]] y [[río Cheyenne|Cheyenne]], todos desde el oeste.<ref name="topoquest"/><ref name="ACMEmapper"/> |

Fluyendo hacia el este a través de las llanuras del este de Montana, el Misuri recibe el [[río Poplar]] desde el norte antes de cruzar a [[Dakota del Norte]], donde el [[río Yellowstone]], su mayor afluente por caudal, se le une desde el suroeste. En la confluencia, el Yellowstone es en realidad el río más grande.{{#tag:ref|The Missouri's flow at [[Culbertson, Montana]], {{convert|25|mi|km|abbr=on}} above the confluence of the two rivers, is about {{convert|9820|cuft/s|m3/s|abbr=on}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2010/pdfs/06185500.2010.pdf|title=USGS Gage #06185500 on the Missouri River near Culbertson, MT|publisher=U.S. Geological Survey|work=National Water Information System|date=1941–2010|accessdate=2011-07-04}}</ref> and the Yellowstone's discharge at [[Sidney, Montana]], roughly the same distance upstream along that river, is about {{convert|12370|cuft/s|m3/s|abbr=on}}.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://wdr.water.usgs.gov/wy2010/pdfs/06329500.2010.pdf|title=USGS Gage #06329000 on the Yellowstone River near Sidney, MT|publisher=U.S. Geological Survey|work=National Water Information System|date=1911–2010|accessdate=2011-07-04}}</ref>|group=n}} El Misuri serpentea luego al este más allá de [[Williston (Dakota del Norte)|Williston]] y en el [[lago Sakakawea]], el embalse formado por la [[presa Garrison]]. Aguas abajo de la presa, el río Misuri recibe al [[río Knife]] desde el oeste y fluye hacia el sur hasta [[Bismarck(Dakota del Norte)|Bismarck]], la capital de Dakota del Norte, donde el río se le une el [[río Heart (Dakota del Norte)|río Heart]], que le aborda desde el oeste. Se ralentiza en el embalse del [[lago Oahe]] justo antes de la confluencia del [[río Cannonball]]. Mientras continúa hacia el sur, finalmente llega a la [[presa Oahe]], en [[Dakota del Sur]], donde se le unen los ríos [[río Grand (Dakota del Sur)|Grand]], [[río Moreau|Moreau]] y [[río Cheyenne|Cheyenne]], todos desde el oeste.<ref name="topoquest"/><ref name="ACMEmapper"/> |

||

El Misuri describe una curva hacia el sureste, y serpentea a través de las Grandes Llanuras, recibiendo al [[río Niobrara]] y muchos pequeños afluentes desde el suroeste. Seguidamente procede a formar la frontera de Dakota del Sur y Nebraska, a continuación, después de haber sido unidos por el [[río James]] por el norte, forma el límite de Iowa-Nebraska. En [[Sioux City]] el [[río Big Sioux]] viene desde el norte. El Misuri fluye hacia el sur a la ciudad de [[Omaha |

El Misuri describe una curva hacia el sureste, y serpentea a través de las Grandes Llanuras, recibiendo al [[río Niobrara]] y muchos pequeños afluentes desde el suroeste. Seguidamente procede a formar la frontera de Dakota del Sur y Nebraska, a continuación, después de haber sido unidos por el [[río James (Nebraska)|río James]] por el norte, forma el límite de Iowa-Nebraska. En [[Sioux City]] el [[río Big Sioux]] viene desde el norte. El Misuri fluye hacia el sur a la ciudad de [[Omaha (Nebraska)|Omaha]] donde recibe a su afluente más largo, el [[río Platte]], desde el oeste.<ref>Twentieth Century Encyclopædia: A Library of Universal Knowledge, Vol. 5, p. 2399</ref> Aguas abajo, comienza a definir la frontera de Nebraska-Misuri, luego fluye entre Misuri y Kansas. El río Misuri se balancea hacia el este en [[Kansas City (Misuri)|Kansas City]], donde el [[río Kansas]] entra desde el oeste, y así sucesivamente en el centro norte de Misuri. Pasa al sur de [[Columbia (Misuri)|Columbia]] y recibe a los ríos [[río Osage|Osage]] y [[río Gasconade|Gasconade]] desdel sur aguas abajo de [[Jefferson City (Misuri)|Jefferson City]]. El río entonces rodea el lado norte de [[St. Louis (Misuri)|St. Louis]] para unirse al río Misisipí en la frontera entre Misuri e [[Illinois]].<ref name="topoquest"/><ref name="ACMEmapper"/> |

||

== Cuenca== |

== Cuenca== |

||

| Línea 53: | Línea 53: | ||

Con más de {{unidad|440000|km²}} bajo el arado, la cuenca del río Misuri incluye más o menos una cuarta parte de todos las tierras agrícolas de los Estados Unidos, proveyendo más de un tercio de la producción de trigo, lino, cebada y avena del país. Sin embargo, sólo {{unidad|28000|km²}} de la tierra de cultivo en la cuenca es de regadío. Otros {{unidad|730000|km²}} de la cuenca se dedican a la cría de ganado, principalmente ganado vacuno. Las áreas forestadas de la cuenca, en su mayoría de segundo crecimiento, son un total de alrededor de {{unidad|113000|km²}}. Las zonas urbanas, por otro lado, representan menos de {{unidad|34000|km²}} de tierra. Las áreas más urbanizadas se encuentran a lo largo del curso principal y en algunos afluentes importantes, como el Platte y el Yellowstone.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/><ref>{{cite news |author=DeFranco, Anthony |title=No More Floods! Build The Missouri River Development Project |url=http://www.21stcenturysciencetech.com/Articles_2011/MissouriRiverProject.pdf |publisher=21st Century Science and Technology |work=New Federalist American Almanac |date=1994-06-27 |accessdate=2012-01-17}}</ref> |

Con más de {{unidad|440000|km²}} bajo el arado, la cuenca del río Misuri incluye más o menos una cuarta parte de todos las tierras agrícolas de los Estados Unidos, proveyendo más de un tercio de la producción de trigo, lino, cebada y avena del país. Sin embargo, sólo {{unidad|28000|km²}} de la tierra de cultivo en la cuenca es de regadío. Otros {{unidad|730000|km²}} de la cuenca se dedican a la cría de ganado, principalmente ganado vacuno. Las áreas forestadas de la cuenca, en su mayoría de segundo crecimiento, son un total de alrededor de {{unidad|113000|km²}}. Las zonas urbanas, por otro lado, representan menos de {{unidad|34000|km²}} de tierra. Las áreas más urbanizadas se encuentran a lo largo del curso principal y en algunos afluentes importantes, como el Platte y el Yellowstone.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/><ref>{{cite news |author=DeFranco, Anthony |title=No More Floods! Build The Missouri River Development Project |url=http://www.21stcenturysciencetech.com/Articles_2011/MissouriRiverProject.pdf |publisher=21st Century Science and Technology |work=New Federalist American Almanac |date=1994-06-27 |accessdate=2012-01-17}}</ref> |

||

Las elevaciones en la cuenca varían ampliamente, desde poco más de {{unidad|120|m}} en la desembocadura del Misuri <ref name="GNIS"/> hasta los {{unidad|4357|m}} de la cima del [[Monte Lincoln (Colorado)|monte Lincoln]] en el centro de Colorado.<ref>{{cite web|title=Mount Lincoln, Colorado|url=http://www.peakbagger.com/peak.aspx?pid=5793|publisher=Peakbagger|accessdate=21 May 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://egsc.usgs.gov/isb/pubs/booklets/elvadist/elvadist.html#14,000 |title=Elevations and Distances in the United States |publisher=U.S. Geological Survey |work=Eastern Geographic Science Center |date=2005-04-29 |accessdate=2010-10-08}}</ref> El propio río cae un total de {{unidad|2629|m}} desde Brower's |

Las elevaciones en la cuenca varían ampliamente, desde poco más de {{unidad|120|m}} en la desembocadura del Misuri <ref name="GNIS"/> hasta los {{unidad|4357|m}} de la cima del [[Monte Lincoln (Colorado)|monte Lincoln]] en el centro de Colorado.<ref>{{cite web|title=Mount Lincoln, Colorado|url=http://www.peakbagger.com/peak.aspx?pid=5793|publisher=Peakbagger|accessdate=21 May 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://egsc.usgs.gov/isb/pubs/booklets/elvadist/elvadist.html#14,000 |title=Elevations and Distances in the United States |publisher=U.S. Geological Survey |work=Eastern Geographic Science Center |date=2005-04-29 |accessdate=2010-10-08}}</ref> El propio río cae un total de {{unidad|2629|m}} desde Brower's Spring, la fuente más lejana. Aunque las llanuras de la cuenca tienen muy poco relieve vertical local, el terreno se eleva unos 1,9 m/km de este a oeste. La altitud es de menos de {{unidad|150|m}} en el borde oriental de la cuenca, pero es más de {{unidad|910|m}} sobre el nivel del mar en muchos lugares en la base de las Rockies.<ref name="ACMEmapper"/> |

||

La cuenca del Misuri tiene patrones climáticos y de precipitaciones muy variables, en general, la cuenca está definida por un [[clima continental]] con veranos cálidos y húmedos e inviernos fríos yseveros. La mayor parte de la cuenca recibe un promedio de 200 a 250 mm de precipitación al año.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/> Sin embargo, las partes más occidentales de la cuenca en las montañas Rocosas, así como las regiones del sureste de Misuri pueden recibir hasta 1000 mm.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/> La gran mayoría de las precipitaciones se produce en invierno, a pesar de que la cuenca alta es conocida por las tormentas de corta duración pero intensas de verano, como la que produjo en la inundación de 1972 en Negro Hills con inundaciones a través de [[Rapid City, South Dakota]], Dakota del Sur.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/fs-037-02/ |title= The 1972 Black Hills-Rapid City Flood Revisited |publisher=U.S. Geological Survey |accessdate=2012-01-15 |author=Carter, Janet M.; Williamson, Joyce E.; Teller, Ralph W.}}</ref> Las temperaturas de invierno en Montana, Wyoming y Colorado pueden bajar hasta -51°C, mientras que las máximos de verano en Kansas y Misuri han llegado a 49°C a veces.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/> |

La cuenca del Misuri tiene patrones climáticos y de precipitaciones muy variables, en general, la cuenca está definida por un [[clima continental]] con veranos cálidos y húmedos e inviernos fríos yseveros. La mayor parte de la cuenca recibe un promedio de 200 a 250 mm de precipitación al año.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/> Sin embargo, las partes más occidentales de la cuenca en las montañas Rocosas, así como las regiones del sureste de Misuri pueden recibir hasta 1000 mm.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/> La gran mayoría de las precipitaciones se produce en invierno, a pesar de que la cuenca alta es conocida por las tormentas de corta duración pero intensas de verano, como la que produjo en la inundación de 1972 en Negro Hills con inundaciones a través de [[Rapid City, South Dakota]], Dakota del Sur.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/fs-037-02/ |title= The 1972 Black Hills-Rapid City Flood Revisited |publisher=U.S. Geological Survey |accessdate=2012-01-15 |author=Carter, Janet M.; Williamson, Joyce E.; Teller, Ralph W.}}</ref> Las temperaturas de invierno en Montana, Wyoming y Colorado pueden bajar hasta -51°C, mientras que las máximos de verano en Kansas y Misuri han llegado a 49°C a veces.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/> |

||

| Línea 75: | Línea 75: | ||

[[File:PawneeVillasur1720.jpg|thumb|Masacre de la Expedición Villasur, pintado c. 1720]] |

[[File:PawneeVillasur1720.jpg|thumb|Masacre de la Expedición Villasur, pintado c. 1720]] |

||

En mayo de 1673 los exploradores franceses [[Louis Jolliet]] y [[Jacques Marquette]] abandonaron el asentamiento de [[St. Ignace |

En mayo de 1673 los exploradores franceses [[Louis Jolliet]] y [[Jacques Marquette]] abandonaron el asentamiento de [[St. Ignace (Míchigan)|St. Ignace]] en el [[lago Huron]] y descendieron por el [[río Wisconsin]] y luego el Mississippi, con el objetivo de llegar al acéano Pacífico. A finales de junio, Jolliet y Marquette se convirtieron en los primeros descubridores europeos documentados del río Misuri, que según sus diarios se encontraba en plena crecida. <ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/diary/001412.asp |title=Aug. 14, 1673: Passing the Missouri |publisher=Wisconsin Historical Society |work=Historic Diaries: Marquette and Joliet |accessdate=2010-11-19}}</ref> "I never saw anything more terrific," Jolliet wrote, "a tangle of entire trees from the mouth of the Pekistanoui [Missouri] with such impetuosity that one could not attempt to cross it without great danger. The commotion was such that the water was made muddy by it and could not clear itself."<ref name="Houck">Houck, pp. 160–161</ref><ref>Kellogg, p. 249</ref> «Nunca vi nada más terrorífico —escribió Jolliet— una maraña de árboles enteros desde la boca del Pekistanoui [Misuri] con tanto ímpetu que no se podía tratar de cruzarlo sin gran peligro. La conmoción era tal que el agua se hacia barro por ello y no podía quedar clara».<ref name="Houck">Houck, pp. 160–161</ref><ref>Kellogg, p. 249</ref> Grabaron ''Pekitanoui'' o ''Pekistanoui'' como el nombre local para el Misuri. Sin embargo, la partida nunca exploró el Misuri más allá de su boca, ni permanecieron en la zona. Además, más tarde se enteraron de que el Mississippi vertía en el golfo de México y no en el Pacífico como habían presumido en un principio; la expedición se volvió a unos {{unidad|710|km}} antes del Golfo, en la confluencia del [[río Arkansas]] con el Mississippi.<ref name="Houck"/> |

||

En 1682, Francia amplió sus reivindicaciones territoriales en América del Norte para incluir la tierra en el lado occidental del río Mississippi, que incluía la parte inferior del Misuri. Sin embargo, el propio Misuri se mantuvo formalmente inexplorado hasta que [[Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont]], al mando de una expedición en 1714, lo remontó al menos hasta la desembocadura del [[río Platte]]. No está claro exactamente lo lejos que Bourgmont viajó más allá de allí; describió las rubias [[mandan]]s en sus diarios, por lo que es probable que llegase hasta sus aldeas en la actual Dakota del Norte.<ref>{{cite news |editor=Blackmar, Frank W. |title=Bourgmont’s Expedition |work=Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history, embracing events, institutions, industries, counties, cities, towns, prominent persons, etc. |year=1912}}</ref> Más tarde, ese mismo año, Bourgmont publicó ''The Route To Be Taken To Ascend The Missouri River'' [La Ruta que debe ser tomada para ascender el río Misuri], el primer documento conocido que utilizór el nombre " |

En 1682, Francia amplió sus reivindicaciones territoriales en América del Norte para incluir la tierra en el lado occidental del río Mississippi, que incluía la parte inferior del Misuri. Sin embargo, el propio Misuri se mantuvo formalmente inexplorado hasta que [[Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont]], al mando de una expedición en 1714, lo remontó al menos hasta la desembocadura del [[río Platte]]. No está claro exactamente lo lejos que Bourgmont viajó más allá de allí; describió las rubias [[mandan]]s en sus diarios, por lo que es probable que llegase hasta sus aldeas en la actual Dakota del Norte.<ref>{{cite news |editor=Blackmar, Frank W. |title=Bourgmont’s Expedition |work=Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history, embracing events, institutions, industries, counties, cities, towns, prominent persons, etc. |year=1912}}</ref> Más tarde, ese mismo año, Bourgmont publicó ''The Route To Be Taken To Ascend The Missouri River'' [La Ruta que debe ser tomada para ascender el río Misuri], el primer documento conocido que utilizór el nombre "río Missouri"; muchos de los nombres que Veniard dio a los afluentes, en su mayoría por las tribus nativas que vivían a lo largo de ellos, se encuentran todavía en uso hoy en día. Los descubrimientos de la expedición finalmente fueron reflejados por el cartógrafo [[Guillaume Delisle]], que utilizó la información para crear un mapa del Misuri inferior.<ref name="Bourgmont">{{cite web |last=Hechenberger |first=Dan |url=http://www.nps.gov/jeff/historyculture/loader.cfm?csModule=security/getfile&pageid=145929 |title=Etienne de Véniard sieur de Bourgmont: timeline |publisher=U.S. National Park Service |accessdate=2011-01-07}}</ref> En 1718, [[Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, señor de Bienville]] pidió que el gobierno francés otorgase a Bourgmont la [[Orden de San Luis|Cruz de St. Louis]] por su "servicio excepcional a Francia".<ref name="Bourgmont"/> |

||

Bourgmont había, de hecho, tenido problemas con las autoridades coloniales francesas desde 1706, cuando abandonó su cargo como comandante de [[Fort Detroit]] |

Bourgmont había, de hecho, tenido problemas con las autoridades coloniales francesas desde 1706, cuando abandonó su cargo como comandante de [[Fort Detroit]] después de mal manejo de un ataque de los [[Ottawa (tribu)|ottawas]] que acabó con treinta y un muertos.<ref>{{cite web |last=Nolan |first=Jenny |url=http://apps.detnews.com/apps/history/index.php?id=180 |title=Chief Pontiac's siege of Detroit |publisher=Detroit News |work=Michigan History |date=2000-06-14 |accessdate=2010-10-04}}</ref> Sin embargo, su reputación quedó reforzada en 1720 cuando los [[pawnee]]s —que antes habían hecho amistad por Bourgmont— masacraron a los españoles de la e[[xpedición Villasur]] cerca de la actual [[Columbus (Nebraska)|Columbus]] (Nebraska) en el río Misuri, terminando temporalmente con la invasión española en la Luisiana francesa.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/markers/texts/villasur_expedition_1720.htm |title=The Villasur Expedition–1720 |publisher=Nebraska State Historical Society |date=2004-06-04 |accessdate=2012-01-19}}</ref> Bourgmont estableció [[Fort Orleans]], el primer asentamiento europeo de ningún tipo sobre el río Misuri, cerca de la actual [[Brunswick (Misuri)|Brunswick]] (Misuri), en 1723. Al año siguiente Bourgmont dirigió una expedición para obtener apoyo de los [[comanche]]s contra los españoles, que continuaron mostrando interés en hacerse con el control del Misuri. En 1725 Bourgmont llevó a los jefes de varias tribus del río Misuri a visitar Francia. Allí fue elevado al rango de la nobleza y no acompañó a los jefes de vuelta a América del Norte. Fort Orleans fue abandonado o su pequeño contingente masacrados por los nativos americanos en 1726.<ref name="Bourgmont"/><ref>Houck, pp. 258–265.</ref> |

||

La [[Guerra Franco-India]] estalló cuando las disputas territoriales entre Francia y Gran Bretaña en América del Norte llegaron a un punto crítico en 1754. En 1763 Francia fue derrotada por la fuerza mucho mayor del ejército británico y se vio obligado a ceder sus posesiones canadienses a los ingleses y la Luisiana a los españoles en el [[Tratado de París (1763)|Tratado de París]] |

La [[Guerra Franco-India]] estalló cuando las disputas territoriales entre Francia y Gran Bretaña en América del Norte llegaron a un punto crítico en 1754. En 1763 Francia fue derrotada por la fuerza mucho mayor del ejército británico y se vio obligado a ceder sus posesiones canadienses a los ingleses y la Luisiana a los españoles en el [[Tratado de París (1763)|Tratado de París]] (1763), afectando a la mayoría de sus posesiones coloniales en América del Norte.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/paris763.asp |title= The definitive Treaty of Peace and Friendship between his Britannick Majesty, the Most Christian King, and the King of Spain. Concluded at Paris the 10th day of February, 1763. To which the King of Portugal acceded on the same day. (Printed from the Copy.) |publisher=Yale Law School |work=The Avalon Project |accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref> |

||

En un principio, los españoles no exploraron extensivamente el Misuri y dejaron que los comerciantes franceses continúaran sus actividades bajo licencia. No obstante, |

En un principio, los españoles no exploraron extensivamente el Misuri y dejaron que los comerciantes franceses continúaran sus actividades bajo licencia. No obstante, esto terminó después de que llegasen noticias de que la [[Compañía de la Bahía de Hudson]] británica estaba haciendo incursiones en la cuenca alta del río Misuri a la vuelta de una expedición de [[Jacques D'Eglise]] en la década de 1790.<ref>{{cite news |last=Nasatir |first=Abraham P. |title=Jacques d’Eglise on the Upper Missouri, 1791–1795 |work=Mississippi Valley Historical Review |pages=47–56 |year=1927 <!--|accessdate=2012-01-19-->}}</ref> En 1795 los españoles garantizaron la Compañía de descubridores y exploradores del Misuri, conocida popularmente como la "Compañía Misuri", y ofrecieron una recompensa por la primera persona en llegar al océano Pacífico a través del Misuri. |

||

In 1794 and 1795 expeditions led by Jean Baptiste Truteau and Antoine Simon Lecuyer de la Jonchšre did not even make it as far north as the Mandan villages in central North Dakota. En 1794 y 1795 las expediciones dirigidas por Jean Baptiste Truteau y Antoine Simon Lecuyer de la Jonchšre ni siquiera lograron llegar tan al norte como para alcanzar las aldeas de los mandan en el centro de Dakota del Norte.<ref name="Evans">{{cite news |last=Williams |first=David |title=John Evans’ Strange Journey: Part II. Following the Trail |work=American Historical Review |year=1949 |pages=508–529<!--|accessdate=2012-01-19-->}}</ref> |

|||

Podría decirse que el mayor éxito de las expediciones de la Compañía del |

Podría decirse que el mayor éxito de las expediciones de la Compañía del Misuri fue la de James MacKay y [[John Evans (explorador)|John Evans]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/lewis_clark_il/htmls/il_country_exp/preps/mackay_evans_map.html |title=The Mackay and Evans Map |publisher=Illinois State Museum |work=Lewis and Clark in the Illinois Country |

||

|accessdate=2012-01-23}}</ref> Las dos se dedicaron a lo largo del |

|accessdate=2012-01-23}}</ref> Las dos se dedicaron a lo largo del Misuri, y estableció Fort Charles cerca de 32 km al sur de la actual Sioux City como campamento de invierno en 1795. En las aldeas mandan en Dakota del Norte, expulsaron a varios comerciantes británicos, y mientras hablaban con el pueblo identificaron la ubicación del río Yellowstone, que fue llamado ''Roche Jaune'' ("Roca Amarilla") por los franceses. Aunque MacKay y Evans no pudieron cumplir con su objetivo original de llegar al Pacífico, crearon el primer mapa preciso de la parte alta del río Misuri.<ref name="Evans"/><ref>{{cite web |last=Witte |first=Kevin C. |url= http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1132&context=greatplainsquarterly |title= In the Footsteps of the Third Spanish Expedition: James Mackay and John T. Evans' Impact on the Lewis and Clark Expedition |publisher=University of Nebraska – Lincoln |work=Great Plains Studies, ''Center for Great Plains Quarterly'' |year=2006 |accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref> |

||

En 1795, los jóvenes Estados Unidos y España firmaron el [[Tratado de Pinckney]], que reconoció los derechos estadounidenses para navegar por el río Mississippi y llevar artículos para la exportación en Nueva Orleans.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.uv.es/EBRIT/micro/micro_468_15.html |title=Pinckney's Treaty or Treaty of San Lorenzo |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica |accessdate=2010-10-04}} {{Dead link|date=April 2012|bot=H3llBot}}</ref> Tres años después, España revocó el tratado y en 1800 en secreto devolvió la Luisiana a a la Francia [[Napoleon Bonaparte|napoleónica]] en el [[Tercer Tratado |

En 1795, los jóvenes Estados Unidos y España firmaron el [[Tratado de Pinckney]], que reconoció los derechos estadounidenses para navegar por el río Mississippi y llevar artículos para la exportación en Nueva Orleans.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.uv.es/EBRIT/micro/micro_468_15.html |title=Pinckney's Treaty or Treaty of San Lorenzo |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica |accessdate=2010-10-04}} {{Dead link|date=April 2012|bot=H3llBot}}</ref> Tres años después, España revocó el tratado y en 1800 en secreto devolvió la Luisiana a a la Francia [[Napoleon Bonaparte|napoleónica]] en el [[Tercer Tratado de San Ildefonso]]. Esta transferencia fue tan secreta que los españoles siguieron administrando el territorio. En 1801, España restauró los derechos de uso del Mississippi y de Nueva Orleans a los Estados Unidos.<ref>{{ cite web|url=http://www.napoleon-series.org/research/government/diplomatic/c_ildefonso.html |title=Treaty of San Ildefonso |publisher=The Napoleon Series |work=Government & Politics |accessdate=2010-10-04}}</ref> |

||

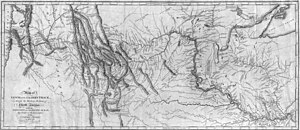

[[File:Map of Lewis and Clark's Track, Across the Western Portion of North America, published 1814.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Mapa del oeste de Norteamérica dibujada por [[Lewis and Clark Expedition|Lewis and Clark]]]] |

[[File:Map of Lewis and Clark's Track, Across the Western Portion of North America, published 1814.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Mapa del oeste de Norteamérica dibujada por [[Lewis and Clark Expedition|Lewis and Clark]]]] |

||

Temiendo que los cortes podrían volver a producirse, el presidente [[Thomas Jefferson]] propuso a Francia comprarle el puerto de Nueva Orleans por $10 millones. En cambio, enfrentado a una crisis de deuda, Napoleón le ofreció vender la totalidad de |

Temiendo que los cortes podrían volver a producirse, el presidente [[Thomas Jefferson]] propuso a Francia comprarle el puerto de Nueva Orleans por $10 millones. En cambio, enfrentado a una crisis de deuda, Napoleón le ofreció vender la totalidad de la Luisiana, incluyendo el río Misuri, por $15 millones, lo que ascendía a menos de 3 centavos de dólar por acre. El acuerdo fue firmado en 1803, duplicando el tamaño de los Estados Unidos con la adquisición del [[territorio de Luisiana]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nps.gov/archive/jeff/lewisclark2/circa1804/heritage/louisianapurchase/louisianapurchase.htm |title=Louisiana Purchase |publisher=U.S. National Park Service |work=The Lewis and Clark Journey of Discovery |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20101129154059/http://www.nps.gov/archive/jeff/lewisclark2/circa1804/heritage/louisianapurchase/louisianapurchase.htm |archivedate=2010-11-29 |accessdate=2010-10-04}}</ref> En 1803, Jefferson instruyó a Meriwether Lewis para explorar el Misuri y buscar una vía navegable hasta el océano Pacífico. Para entonces, se había descubierto que el sistema del río Columbia, que desemboca en el Pacífico, tenía una latitud similar a la de las cabeceras del río Misuri, y se creía ampliamente que una conexión o corto porteo debía de existir entre ambos.<ref name="lewis1">{{cite web |title = Jefferson's Instructions for Meriwether Lewis |url = http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/lewisandclark/lewis-landc.html#57 |publisher=U.S. Library of Congress |accessdate=2006-06-30}}</ref> Sin embargo, España se opuso a la toma de posesión, alegando que nunca habían devuelto formalmente la Luisiana a los franceses. Las autoridades españolas advirtieron a Lewis que no hiciese el viaje y le prohibieron ver el mapa de MacKay y Evans del Misuri, aunque Lewis finalmente logró tener acceso a él.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/lewis_clark_il/htmls/il_country_exp/preps/mackay_evans_map.html |title=The Mackay and Evans Map |publisher=The Illinois State Museum |work=Lewis and Clark in the Illinois Country |accessdate=2011-01-06}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www2.lib.virginia.edu/exhibits/lewis_clark/exploring/ch4.html |title=To the Western Ocean: Planning the Lewis and Clark Expedition |publisher=University of Virginia Library |work=Exploring the West from Monticello: A Perspective in Maps from Columbus to Lewis and Clark |accessdate=2011-01-06}}</ref> |

||

Meriwether Lewis y [[William Clark]] comenzaron su famosa expedición en 1804 con un grupo de treinta y tres personas en tres embarcaciones..<ref name="L&C2">{{cite web |url=http://www.nationalgeographic.com/lewisandclark/journey_leg_1.html |title=The Journey Begins |publisher=National Geographic |work=Lewis & Clark Interactive Journey Log |

Meriwether Lewis y [[William Clark]] comenzaron su famosa expedición en 1804 con un grupo de treinta y tres personas en tres embarcaciones..<ref name="L&C2">{{cite web |url=http://www.nationalgeographic.com/lewisandclark/journey_leg_1.html |title=The Journey Begins |publisher=National Geographic |work=Lewis & Clark Interactive Journey Log |

||

|accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref> A pesar de que se convirtieron en los primeros europeos que viajaron a todo lo largo del |

|accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref> A pesar de que se convirtieron en los primeros europeos que viajaron a todo lo largo del Misuri y llegaron al Pacífico vía el río Columbia, no encontraron ningún rastro del Paso del Noroeste. Los mapas realizados por Lewis y Clark, en especial los de la región del [[Pacífico Noroeste]], proporcionaron la base para los futuros exploradores y emigrantes. También negociaron las relaciones con múltiples tribus nativas americanas y escribieron extensos informes sobre el clima, la ecología y la geología de la región. Muchos nombres actuales de los accidentes geográficos de la cuenca alta Misuri se originaron a partir de su expedición.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/lewisandclark/intro.htm |title=Introduction |publisher=U.S. National Park Service |work=Lewis and Clark Expedition: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary |accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref> |

||

== Frontera americana== |

== Frontera americana== |

||

| Línea 104: | Línea 104: | ||

[[File:George Caleb Bingham 001.jpg|thumb|right|''Fur Traders on Missouri River'', pintada por [[George Caleb Bingham]] c. 1845]] |

[[File:George Caleb Bingham 001.jpg|thumb|right|''Fur Traders on Missouri River'', pintada por [[George Caleb Bingham]] c. 1845]] |

||

A inicios del siglo XIX, los cazadores de pieles entraron en el extremo norte de la cuenca del río |

A inicios del siglo XIX, los cazadores de pieles entraron en el extremo norte de la cuenca del río Misuri en la esperanza de encontrar poblaciones de [[castor]] y de [[nutria de río]], cuya venta de pieles condujo el próspero [[comercio de pieles de América del Norte]]. Venían de muchos lugares diferentes, unos de las corporaciones de piel canadienses en la bahía de Hudson, algunos desde el Noroeste del Pacífico (véase también [[Comercio Marítimo de pieles]]), y algunos de medio oeste de Estados Unidos. La mayoría no se quedaron en la zona por mucho tiempo, ya que no lograron encontrar recursos significativos.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://lewis-clark.org/content/content-article.asp?ArticleID=2970 |title=Manuel Lisa's Fort Raymond: First Post in the Far West |publisher=The Lewis and Clark Fort Mandan Foundation |work=Discovering Lewis and Clark |accessdate=2010-10-18}}</ref> |

||

Los primeros informes entusiastas de un país rico con miles de animales de caza se produjo en 1806 cuando Meriwether Lewis y William Clark regresaron de su expedición de dos años. Sus publicaciones describían tierras ricas con miles de bisontes, castores y nutrias de río; y también una abundante población de [[nutrias de mar]] en la [[costa noroeste del Pacífico]]. En 1807, el explorador [[Manuel Lisa]] organizó una expedición que llevaría al crecimiento explosivo del comercio de la piel en las regiones superiores del río Misuri. Lisa y su partida remontaron los ríos |

Los primeros informes entusiastas de un país rico con miles de animales de caza se produjo en 1806 cuando Meriwether Lewis y William Clark regresaron de su expedición de dos años. Sus publicaciones describían tierras ricas con miles de bisontes, castores y nutrias de río; y también una abundante población de [[nutrias de mar]] en la [[costa noroeste del Pacífico]]. En 1807, el explorador [[Manuel Lisa]] organizó una expedición que llevaría al crecimiento explosivo del comercio de la piel en las regiones superiores del río Misuri. Lisa y su partida remontaron los ríos Misuri y Yellowstone, comerciando artículos manufacturados a cambio de pieles con las tribus nativas locales, y establecieron un fuerte en la confluencia de los ríos Yellowstone y uno de sus afluentes, el Bighorn, en el sur de Montana. Aunque el negocio comenzó siendo pequeño, se convirtió rápidamente en un próspero comercio.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/fur-trader-manuel-lisa-dies |title=Fur trader Manuel Lisa dies |publisher=A&E Television Networks |work=This Day in History |accessdate=2010-10-18}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://lewis-clark.org/content/content-article.asp?ArticleID=2868 |title=Post-Expedition Fur Trade: "The Great Engine" |publisher=The Lewis and Clark Fort Mandan Foundation |work=Discovering Lewis and Clark |accessdate=2010-10-19}}</ref> |

||

Los hombres de Lisa comenzó la construcción de [[Fort Raymond]], que estaba asentado en un acantilado con vistas a la confluencia de los ríos Yellowstone y Bighorn, en el otoño de 1807. El fuerte serviría principalmente como un puesto comercial para el trueque con los nativos por pieles.<ref>Morris, pp. 40–41</ref> Este método era diferente al del comercio de pieles del Noroeste del Pacífico, que involucraba a cazadores contratados por las distintas empresas de piel, principalmente por la [[Compañía de la bahía de Hudson]]. Fort Raymond fue sustituido más tarde por [[Fort Lisa (Dakota del Norte)|Fort Lisa]] |

Los hombres de Lisa comenzó la construcción de [[Fort Raymond]], que estaba asentado en un acantilado con vistas a la confluencia de los ríos Yellowstone y Bighorn, en el otoño de 1807. El fuerte serviría principalmente como un puesto comercial para el trueque con los nativos por pieles.<ref>Morris, pp. 40–41</ref> Este método era diferente al del comercio de pieles del Noroeste del Pacífico, que involucraba a cazadores contratados por las distintas empresas de piel, principalmente por la [[Compañía de la bahía de Hudson]]. Fort Raymond fue sustituido más tarde por [[Fort Lisa (Dakota del Norte)|Fort Lisa]] en la confluencia del Misuri y Yellowstone en Dakota del Norte; una segunda fortaleza también llamada [[Fort Lisa (Nebraska)|Fort Lisa]] fue construida aguas abajo en el río Misuri en Nebraska. En 1809 fue fundada la [[St. Louis Missouri Fur Company]] por Lisa junto con William Clark y [[Pierre Choteau]], entre otros.ref>South Dakota State Historical Society & South Dakota Department of History pp. 320–325</ref><ref name="npsfur">{{cite web |url=http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/travel/pierre_fortpierre/early_exploration_fur_trade_essay.html |title=Early Exploration and the Fur Trade |publisher=U.S. National Park Service |accessdate=2010-10-19}}</ref> En 1828, la [[American Fur Company]] fundó [[Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site|Fort Union]] en la confluencia de los ríos Misuri y Yellowstone. Fort Union se convirtió gradualmente en la sede principal del comercio de la piel en la cuenca alta del Misuri.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/lewisandclark/uni.htm |title=Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site |publisher=U.S. National Park Service |work=Lewis & Clark Expedition |accessdate=2012-02-11}}</ref> |

||

La captura de pieles a principios del siglo XIX se realizaron casi en la totalidad de las montañas Rocosas, en ambas vertientes, oriental y occidental. Los cazadores y tramperos de la Compañía de la Bahía de Hudson, |

La captura de pieles a principios del siglo XIX se realizaron casi en la totalidad de las montañas Rocosas, en ambas vertientes, oriental y occidental. Los cazadores y tramperos de la Compañía de la Bahía de Hudson, St. Louis Missouri Fur Company, American Fur Company, [[Rocky Mountain Fur Company]], [[North West Company]] y otros equipos trabajaron miles de arroyos de la cuenca de Misuri, así como de los vecinos sistemas fluviales del Columbia, Colorado, Arkansas y Saskatchewan. Durante ese período los tramperos, también llamados hombres de la montaña, abrieron senderos a través de tierras virgenes, que más tarde formarían los caminos por los que los pioneros y colonos viajarían en el Oeste. El transporte de las miles de pieles de castor requerió embarcaciones, proporcionando una de los primeras grandes motivos para que comenzase el transporte fluvial en el Misuri.<ref>Sunder, p. 10</ref> |

||

Cuando acabó la década de 1830, la industria de la piel poco a poco comenzó a morir ya que la seda estaba reemplazado a las pieles de castor como deseada prenda de vestir. En ese momento, también, la población de castores de los arroyos en las montañas Rocosas había sido diezmada por la caza intensa. Por otra parte, los frecuentes ataques de los nativos a los puestos comerciales hicieron que esto fuera peligroso para los empleados de las empresas de piel. En algunas regiones, la industria continuó hasta bien entrada la década de 1840, pero en otras, como en el valle del río Platte, las disminuciones de la población de castores contribuyó a una muerte temprana.<ref>Sunder, p. 8</ref> El comercio de pieles, finalmente, desapareció en las Grandes Llanuras en 1850, con el centro principal de la industria cambiando al valle del Misisipí y el centro de Canadá. A pesar de la desaparición del comercio una vez próspero, sin embargo, su legado llevó a la apertura del Oeste americano y a una inundación de colonos, granjeros, rancheros, aventureros y empresarios que tomaron su lugar.<ref>Sunder, pp. 12–15</ref> |

|||

=== Asentamientos y pioneros=== |

=== Asentamientos y pioneros=== |

||

{{ |

{{VT|Department of the Missouri|American Indian Wars}} |

||

[[File:George Caleb Bingham - Boatmen on the Missouri - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|''Boatmen on the Missouri'' |

[[File:George Caleb Bingham - Boatmen on the Missouri - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|''Boatmen on the Missouri'' ca. 1846]] |

||

The river roughly defined the [[Frontier#American frontier|American frontier]] in the 19th century, particularly downstream from Kansas City, where it takes a sharp eastern turn into the heart of the state of Missouri. The major trails for the opening of the American West all have their starting points on the river, including the [[California Trail|California]], [[Mormon Trail|Mormon]], [[Oregon Trail|Oregon]], and [[Santa Fe Trail|Santa Fe]] trails. The first westward leg of the [[Pony Express]] was a ferry across the Missouri at [[St. Joseph, Missouri]]. Similarly, most emigrants arrived at the eastern terminus of the [[First Transcontinental Railroad]] via a ferry ride across the Missouri between [[Council Bluffs, Iowa]] and Omaha.<ref>Dick, pp. 127–132</ref><ref>{{cite web |

|||

For most, the route took them up the Missouri to Omaha, Nebraska, where they would [[Great Platte River Road|set out along the Platte River]], which flows from the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming and Colorado eastwards through the Great Plains. An early expedition led by [[Robert Stuart (explorer)|Robert Stuart]] from 1812 to 1813 proved the Platte impossible to navigate by the [[dugout canoe]]s they used, let alone the large sidewheelers and sternwheelers that would later ply the Missouri in increasing numbers. One explorer remarked that the Platte was "too thick to drink, too thin to plow".<ref>Cech, p. 424</ref> |

|||

|url=http://www.history.com/topics/transcontinental-railroad |title=The Transcontinental Railroad |publisher=History Channel |work=History.com |accessdate=2010-10-07}}</ref> The [[Hannibal Bridge]] became the first bridge to cross the Missouri River in 1869, and its location was a major reason why Kansas City became the largest city on the river upstream from its mouth at St. Louis.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.kclibrary.org/?q=blog/week-kansas-city-history/bridge-future |title=Bridge to the Future |publisher=Kansas City Public Library |date=2009-12-09 |accessdate=2010-10-07}}</ref> |

|||

El río más o menos definida la frontera estadounidense en el siglo XIX, sobre todo aguas abajo de Kansas City, donde da un giro oriental enfilado en el corazón del estado de Misuri. Los principales caminos para la apertura del [[Oeste americano]] tienen todos sus puntos de partida en el río, incluyendo las rutas de [[California Trail|California]], [[Mormon Trail|Mormon]], [[Oregon Trail|Oregon]] y [[Santa Fe Trail|Santa Fe]]. El primer puesto de ida hacia el oeste de la [[Pony Express]] era un ferry que atravesaba el Misuri en [[St. Joseph (Misuri)|St. Joseph]], Misuri. Del mismo modo, la mayoría de los emigrantes llegaron al término del este del [[primer ferrocarril transcontinental]] vía un ferry que cruzaba el Misuri entre [[Council Bluffs (Iowa)|Council Bluffs]] (Iowa) y Omaha.<ref>Dick, pp. 127–132</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.history.com/topics/transcontinental-railroad |title=The Transcontinental Railroad |publisher=History Channel |work=History.com |accessdate=2010-10-07}}</ref> El [[puente de Hannibal]] fue el primer puente que cruzó el río Misuri en 1869, y su ubicación fue una importante razón por la que Kansas City se convirtió en la ciudad más grande en el río aguas arriba de su desembocadura en St. Louis.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.kclibrary.org/?q=blog/week-kansas-city-history/bridge-future |title=Bridge to the Future |publisher=Kansas City Public Library |date=2009-12-09 |accessdate=2010-10-07}}</ref> |

|||

Fieles a la continuación del ideal del [[Destino Manifiesto]], más de 500.000 personas salieron de la ciudad ribereña de [[Independence (Misuri)|Independence]] (Misuri), hacia sus diferentes destinos en el oeste de Estados Unidos desde la década de 1830 hasta la década de 1860. Estas personas tenían muchas razones para embarcarse en ese viaje de un año agotador —crisis económica y fibres del oro posteriores, como la [[fiebre del oro de California]], por ejemplo.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/books/ourbooks/mattes.htm |title=The Great Platte River Road |publisher=Nebraska State Historical Society |date=1998-06-30 |accessdate=2011-01-07}}</ref> Para la mayoría, la ruta los llevó por el Misuri hasta Omaha, Nebraska, donde lo harían establecido a lo largo del río Platte, que fluye desde las montañas Rocosas en Wyoming y Colorado hacia el este a través de las Grandes Llanuras. Una temprana expedición dirigida por [[Robert Stuart (explorador)|Robert Stuart]] 1812-1813 probó que en el Platte era imposible navegar con las canoas que usaban, por no hablar de los grandes sidewheelers y barcos a vapor que luego se surcan las Misuri en números crecientes. Un explorador señaló que el Platte era "demasiado gruesa como para beber, demasiado delgada para arar" "too thick to drink, too thin to plow". <ref>Cech, p. 424</ref> |

|||

Sin embargo, el Platte proporcionaba una fuente abundante y confiable de agua para los pioneros que se dirigían al Oeste. Carros cubiertos, conocidos popularmente como «goletas de las pradera» (''prairie schooners''), fueron los principales medios de transporte hasta el inicio del servicio regular de barcos en el río en la década de 1850.<ref>Mattes, pp. 4–11</ref> |

|||

Durante la década de 1860, las fiebres del oro en Montana, Colorado, Wyoming y el norte de Utah atrajeron otra oleada de aspirantes a la región. Aunque una cierta carga fue transportada por tierra, la mayor parte del transporte hacia y desde los campos de oro se llevó a cabo a través de los ríos Misuri y Kansas, así como por el [[río Snake]] en Wyoming occidental y el [[río Bear (Utah)|río Bear]] en Utah, Idaho y Wyoming.<ref>Holmes, Walter and Dailey, pp. 105–106.</ref> Se estima que de los pasajeros y la carga transportada desde el Medio Oeste hasta Montana, más del 80% fueron transportados por embarcaciones, un viaje que llevaba 150 días en la dirección aguas arriba. Una ruta más directa hacia el Oeste en Colorado se extendía a lo largo del río Kansas y su afluente el [[río Republican]], así como un par de pequeños arroyos en Colorado, [[arroyo Big Sandy (Colorado)|Big Sandy]] y el [[río South Platte]], hasta cerca de Denver. Las fiebres del oro precipitaron la decadencia de la [[ruta de Bozeman]] como ruta de emigración popular, ya que pasaba a través de tierras pertenecientes a los a menudo hostiles nativos americanos. Se abrieron caminos más seguros al [[Great Salt Lake]] cerca de [[Corinne, Utah]] (Utah), durante el período de las fiebre del oro, lo que llevó a asentamientos a gran escala en la región de las montañas Rocosas y la [[Gran Cuenca]] oriental.<ref>Athearn, pp. 87–88.</ref> |

|||

[[File:bodmer5455.jpg|thumb|left|180px|Karl Bodmer, ''[[Fort Pierre, South Dakota|Fort Pierre]] and the Adjacent Prairie'', c. 1833]] |

|||

Cuando los colonos ampliaron sus propiedades en las Grandes Llanuras, se toparon con conflictos de tierras con las tribus nativas americanas. Esto dio lugar a frecuentes incursiones, masacres y conflictos armados, lo que lleva al gobierno federal a la creación de múltiples tratados con las tribus de las llanuras, que generalmente suponían establecer fronteras y reserva de tierras para los indígenas. Al igual que con muchos otros tratados entre los nativos americanos y los EE.UU., pronto fueron rotos, lo que llevó a grandes guerras. Más de 1.000 batallas, grandes y pequeñas, se libraron entre los militares de EE.UU. y los nativos americanos antes de que las tribus fueran expulsados de sus tierras a reservas.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/interview/tcrr-interview/ |title=Native Americans |publisher=PBS |work=Transcontinental Railroad: The Film |accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.history.army.mil/html/reference/army_flag/iw.html |title=U.S. Army Campaigns: Indian Wars |publisher=U.S. Army Center of Military History |date=2009-08-03 |accessdate=2010-10-07}}</ref> |

|||

Los conflictos entre los nativos y los colonos durante la apertura de la ruta de Bozeman en las Dakotas, Wyoming y Montana llevó a la [[Guerra de Nube Roja]], en la que los lakotas y cheyennes lucharon contra el Ejército de los EE.UU.. La lucha acabó en una completa victoria de los nativos americanos.<ref>{{cite news |title=Red Cloud's War (United States history) |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica |accessdate=2010-10-05 |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1563057/Red-Clouds-War}}</ref> En 1868, se firmó el [[Tratado de Fort Laramie]], que "garantiza" el uso de la [[Black Hills]], [[Powder River Country]] y otras regiones que rodean el norte del río Misuri para los nativos americanos sin intervención blanca.<ref name="Laramie1868">{{cite web |last=Clark |first=Linda Darus |url=http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/sioux-treaty/ |title=Teaching with Documents: Sioux Treaty of 1868 |publisher=National Archives |work=Expansion & Reform |accessdate=2010-11-10}}</ref> El río Misuri fue también un hito importante dado que divide el noreste de Kansas del oeste de Misuri. Las fuerzas esclavistas de Misuri cruzarían el río en Kansas y desataron el caos durante [[Bleeding Kansas]], lo que lleva a la continua tensión y hostilidad aún hoy entre [[Kansas y Misuri]]. Otro conflicto militar significativa en el río Misuri durante este período fue la [[batalla de Boonville]] de 1861, que no afectó los nativos americanos, sino más bien fue un punto de inflexión en la [[guerra civil americana]] que permitió a la [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] tomar el control del transporte en el río, desalentando al estado de Misuri de unirse a la [[Confederate States of America|Confederación]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cr.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/mo001.htm |title=Boonville |publisher=U.S. National Park Service |work=CWSAC Battle Summaries |accessdate=2011-03-05}}</ref> |

|||

Sin embargo, la paz y la libertad de los nativos americanos no duró mucho tiempo. La [[Gran Guerra Sioux]] de 1876-77 se desató cuando los mineros estadounidenses descubrieron oro en las Black Hills del occidente de Dakota del Sur y oriente de Wyoming. Estas tierras se establecieron originalmente como reserva para uso de los nativos americanos por el Tratado de Fort Laramie.<ref name="Laramie1868"/> Cuando los colonos penetraron en las tierras, fueron atacados por los nativos americanos. Las tropas estadounidenses fueron enviados a la zona para proteger a los mineros, y expulsar a los nativos de los nuevos asentamientos. Durante ese período sangriento, tanto los nativos americanos como los militares de EE.UU. ganaron victorias en grandes batallas, lo que resulta en la pérdida de casi un millar de vidas. La guerra finalmente terminó en una victoria americana, y las Black Hills fueron abiertas a la colonización. Los nativos americanos de la región fueron trasladados a las reservas en Wyoming y el sureste de Montana.<ref>Greene, pp. xv–xxvi</ref> |

|||

== La era de la construcción de presas== |

|||

[[Image:HolterDam1918.jpg|thumb||[[Holter Dam]], una presa run-of-the-river en el alto Misuri, poco despues de su finalización en 1918]] |

|||

{{Further2|[[List of dams in the Missouri River watershed]]}} |

|||

[[Image:Black Eagle Dam 1908 DYK.jpg|thumb|right|170px|Black Eagle Dam fue dinamitada en 1908 para salvar Great Falls de la inundación causada por la rotura de la presa de Hauser]] |

|||

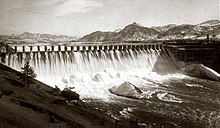

A finales del siglo XIX y principios del XX, se construyeron a lo largo del curso del Misuri un gran número de presas transformando el 35% del río en una cadena de embalses.<ref name="Story"/> El desarrollo del río se vio estimulado por una variedad de factores, en primer lugar por la creciente demanda de electricidad en las zonas rurales del noroeste de la cuenca, y también para evitar las inundaciones y las sequías que asolaron rápidamente las crecientes zonas agrícolas y urbanas a lo largo de la parte baja del río Misuri.<ref name="Pick-Sloan"/> Se abordaron pequeños proyectos hidroeléctricos, de propiedad privada, desde la década de 1890, pero las grandes presas para el control de las inundaciones y el embalsamiento que caracterizan el curso medio del río hoy en día no se construyeron hasta la década de 1950.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/><ref name="Pick-Sloan"/> |

|||

Entre 1890 y 1940 se construyeron cinco presas en las cercanías de [[Great Falls, Montana|Great Falls]] para generar energía a partir de las [[Great Falls of the Missouri]], una cadena de gigantes cascadas formadas por el río a su paso por el oeste de Montana. [[Black Eagle Dam]], construida en 1891 en [[Black Eagle Falls]], fue la primera presa del Misuri.<ref>''Montana: A State Guide Book'', p. 150</ref> Reemplazada en 1926 con una estructura más moderna, la presa era poco más que un pequeño azud en la cima de las Black Eagle Falls, que desviaba parte del caudal del Misuri en la planta de energía de Black Eagle.<ref name="BlackEagleDam">{{cite web |url=http://www.pplmontana.com/producing+power/power+plants/Black+Eagle+Dam.htm |title=Black Eagle Dam |publisher=PPL Montana |work=Producing Power |accessdate=2010-10-07}}</ref> La mayor de las cinco presas, [[Ryan Dam]], fue construida en 1913. La presa se encuentra justo por encima de los 27 m de [[Great Falls (Missouri River waterfall)|Great Falls]], la cascada más grande del Misuri.<ref name="RyanDam">{{cite web |url=http://www.pplmontana.com/producing+power/power+plants/Ryan+Dam.htm |title=Ryan Dam |publisher=PPL Montana |work=Producing Power |accessdate=2010-10-08}}</ref> |

|||

En el mismo período, varios establecimientos privados -más notablemente la [[Montana Power Company]]- comenzaron a desarrollar el río Misuri para la generación eléctrica por encima de Great Falls y por debajo [[Helena, Montana|Helena]]. Un pequeño filo de la estructura río fue completada en 1898 cerca del sitio actual de [[Canyon Ferry Dam]] se convirtió en la segunda presa a construirse en el Misuri. Esta presa llena de rocas generaba 7,5 megavatios de electricidad para Helena y el campo circundante.<ref>Mulvaney, p. 112</ref> La cercana presa de Hauser, una [[presa de acero]], se terminó en 1907, pero falló en 1908 debido a deficiencias estructurales, causando inundaciones catastróficas en todo el curso aguas abajo hasta pasado [[Craig (Montana)|Craig]]. En Great Falls, una sección de la presa Black Eagle fue dinamitada para salvar las fábricas cercanas de la inundación.<ref>Mulvaney, p. 39</ref> Hauser fue reconstruida en 1910 como una estructura de gravedad de hormigón, y todavía permanece en la actualidad.<ref name="Hauser">{{cite web |url=http://www.pplmontana.com/producing+power/power+plants/Hauser+Dam.htm |title=Hauser Dam |work=Producing Power |publisher=PPL Montana |accessdate=2010-12-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://helenair.com/news/local/article_ab5ce658-c9e1-5ade-a9c4-8b371a5ceecf.html |title=Original Hauser Dam fell to mighty Missouri |last=Kline |first=Larry |publisher=Helena Independent Record |date=2008-04-15 |accessdate=2010-12-02}}</ref> |

|||

A small [[Run-of-the-river hydroelectricity|run-of-the river]] structure completed in 1898 near the present site of [[Canyon Ferry Dam]] became the second dam to be built on the Missouri. This rock-filled [[Dam#Timber dams|timber crib dam]] generated seven and a half [[megawatt]]s of electricity for Helena and the surrounding countryside.<ref>Mulvaney, p. 112</ref> |

|||

La [[presa Holter]], a unos {{unidad|72|km}} aguas abajo de Helena, fue la tercera presa hidroeléctrica construida en este tramo del río Misuri.<ref name="HolterDam">{{cite web |url=http://www.pplmontana.com/producing+power/power+plants/Holter+Dam.htm |title=Holter Dam |publisher=PPL Montana |work=Producing Power |accessdate=2010-10-07}}</ref> Cuando fue completado en 1918 por la Montana Power Company y la [[United Missouri River Power Company]], su embalse inundó las [[Gates of the Mountains Wilderness|Gates of the Mountains]], un cañón de piedra caliza que Meriwether Lewis describió como «los acantilados más notables que hemos visto todavía... los torreones y las rocas que sobresalen en muchos lugares parecen dispuestos a caer sobre nosotros». <ref> "the most remarkable clifts that we have yet seen… the tow[er]ing and projecting rocks in many places seem ready to tumble on us."{{cite web |url=http://www.mbmg.mtech.edu/gmr/lewis_clark/lewis_clark-gates.asp |title=Gates of the Mountains |publisher=Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology |work=Lewis and Clark–A Geologic Perspective |accessdate=2012-01-16}}</ref> En 1949, el [[U.S. Bureau of Reclamation]] (USBR) comenzó la construcción de la moderna Canyon Ferry Dam para el control de inundaciones en la zona de Great Falls. En 1954, las aguas cayentes del [[Canyon Ferry Lake]] sumergieron la antigua presa de 1898, cuya casa de máquinas sigue en pie bajo el agua cerca de {{unidad|2.4|km}} aguas arriba de la presa actual.<ref name="CanyonFerryDam">{{cite web |url=http://www.usbr.gov/projects/Facility.jsp?fac_Name=Canyon+Ferry+Dam&groupName=General |title=Canyon Ferry Dam |publisher=U.S. Bureau of Reclamation |date=2010-08-10 |accessdate=2011-01-07}}</ref> |

|||

<blockquote class="toccolours" style="text-align:justify; width:30%; float:left; padding:10px 15px; display:table;">"[The Missouri's temperament was] uncertain as the actions of a jury or the state of a woman's mind." <br/><small>–''Sioux City Register'', March 28, 1868<ref name="RNA438"/></small></blockquote> |

|||

La cuenca del Misuri sufrió una serie de catastróficas inundaciones alrededor del cambio del siglo XX, sobre todo en [[Great Flood of 1844|1844]], [[Great Flood of 1881|1881]], and [[Great Mississippi Flood of 1927|1926–1927]].<ref name="flooding"/> En 1940, como parte de la [[Gran Depresión]]-era del [[New Deal]], el [[Cuerpo de Ingenieros del Ejército de los EE.UU.]] (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, USACE) completó Fort Peck Dam, en Montana. La construcción de este enorme proyecto de obras públicas proporcionó empleo a más de {{unidad|50000|trabajadores}} durante la Gran Depresión y fue un paso importante en el control de inundaciones en la mitad inferior del río Misuri.<ref>{{cite news |author=Johnson, Marc |url=http://www.newwest.net/topic/article/dam_politics_could_a_project_like_fort_peck_get_built_today/C37/L37/ |title=Dam Politics: Could a Project Like Fort Peck Get Built Today? |work=New West Politics |date=2011-05-20 |accessdate=2012-01-16}}</ref> Sin embargo, Fort Peck sólo controla la de escorrentía del 11% de las cuencas del río Misuri, y tuvo poco efecto en una inundación grave por deshielo que azotó la cuenca baja tres años después. Este evento fue especialmente destructivo, ya que sumergió las plantas de fabricación en Omaha y Kansas City, lo que retrasó considerablemente los envíos de suministros militares en la Segunda Guerra Mundial.<ref name="flooding">{{cite web |url=http://www.dnr.state.ne.us/floodplain/mitigation/mofloods.html |title=Historic Floods on the Missouri River: Fighting the Big Muddy in Nebraska |publisher=Nebraska Department of Natural Resources |accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nwk.usace.army.mil/pa/History/timeline-1938-1947.pdf |title=The Fourth Decade of the Kansas City District: 1938–1947 |publisher=U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |accessdate=2012-01-19}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Pick-Sloan Plan.png|thumb|left|Mapa mostrando los principales accidentes de la [[Pick–Sloan Plan]]; otras presas y sus embalses se muestran con triángulos]] |

|||

[[Image:Fort Peck Dam (Fort Peck Montana) 1986 01.jpg|thumb|left|[[Fort Peck Dam]], la presa a más altitud en el Missouri River Mainstem System]] |

|||

Daños de la inundación en el sistema del río Mississippi-Misuri fueron una de las razones principales por la cual el Congreso aprobó la Ley de Control de Inundaciones de 1944, abriendo el camino para que el Cuerpo de Ingenieros desarrollase el Misuri en una escala masiva.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fws.gov/laws/lawsdigest/flood.html |title=Flood Control Act of 1944 |publisher=U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |work=Digest of Federal Resource Laws of Interest to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.msaconline.com /Missouri%20River%20Basin%20Project%20-%20The%20System.htm |title=Missouri River Basin Project: The System |publisher=Missouri Sediment Action Coalition |year=2011 |

|||

|accessdate=2012-03-10}}</ref> El acto 1944 autorizado el Programa Pick Sloan Misuri Cuenca (Pick-Sloan PGOU), que fue una combinación de dos propuestas muy diferentes. El plan de Pick, con énfasis en el control de inundaciones y la energía hidroeléctrica, pidió la construcción de grandes presas de almacenamiento a lo largo del tallo principal del Misuri. El plan de Sloan, que hizo hincapié en el desarrollo de la irrigación local, incluía disposiciones para aproximadamente 85 presas más pequeñas en los afluentes.<ref name="Pick-Sloan">{{cite web |last=Reuss |first=Martin |url=http://140.194.76.129/publications/eng-pamphlets/ep870-1-42/c-4-2.pdf |title=The Pick-Sloan Plan |publisher=U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |work=Engineer Pamphlets |accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref><ref name="Otstot">{{cite web |author=Otstot, Roger S. |url=http://mo-rast.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/2011.09.27-Continued-Pick-Sloan-Presentation-Roger-Otstot.pdf |title=Pick-Sloan Missouri River Basin Program: Hydropower and Irrigation |publisher=Missouri River Association of States and Tribes |work=U.S. Bureau of Reclamation |date=2011-09-27 |accessdate=2012-01-14}}</ref> |

|||

En las primeras etapas del desarrollo Pick–Sloan, se hicieron planes tentativos para construir una presa baja en el Misuri en Riverdale, Dakota del Norte y 27 presas más pequeñas en el río Yellowstone y sus afluentes.<ref>{{cite news |title=Missouri River Basin: Report of a Committee of Two Representatives Each from the Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army, and the Bureau of Reclamation, Appointed to Review the Features Presented by the Corps of Engineers (House Document No. 475) and the Bureau of Reclamation (Senate Document No. 191) for the Comprehensive Development of the Missouri River Basin |publisher=U.S. Congress |work=78th Congress, 2nd Session |date=1944-11-21}}</ref> Esto se cumplió con la controversia de los habitantes de la cuenca de Yellowstone, y, finalmente, el USBR propuso una solución: aumentar en gran medida el tamaño de la presa propuesta en Riverdale - actual Guarnición Dam, sustituyendo así el almacenamiento que proporcionaban las presas de Yellowstone. Debido a esta decisión, el Yellowstone es ahora el río de flujo libre más larga en los estados contiguos de Estados Unidos.<ref>{{cite web |author=Bon, Kevin W. |url=http://library.fws.gov/Wetlands/upperyellowstone_01.pdf |title=Upper Yellowstone River Mapping Project |publisher=U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |date=July 2001 |accessdate=2012-01-14}}</ref> En la década de 1950, la construcción comenzó en los cinco embalses del cauce principal – Garrison, Oahe, [[Big Bend Dam|Big Bend]], [[Fort Randall Dam|Fort Randall]] and [[Gavins Point Dam|Gavins Point]] – propuestas en el marco del Plan de Pick Sloan. [141] Junto con Fort Peck, que se integró como una unidad del Plan Pick Sloan en la década de 1940, estas presas ahora forman lo que se conoce como el Sistema de cauce principal del Río Misuri.[161] |

|||

Tél mesa en listas estadísticas izquierdos de todos los quince represas en el río Missouri, ordenó aguas abajo. [13] Muchas de las presas run-of-the-river en el Missouri (marcado en amarillo) de forma muy pequeños embalses que pueden o no tener han dado nombres; los sin nombre se dejan en blanco. Todas las presas se encuentran en la mitad superior del río por encima de Sioux City; la parte baja del río es ininterrumpido debido a su uso desde hace mucho tiempo como un canal de navegación. [176] |

|||

Flooding damages on the Mississippi–Missouri river system were one of the primary reasons for which [[United States Congress|Congress]] passed the [[Flood Control Act of 1944]], opening the way for the USACE to develop the Missouri on a massive scale.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fws.gov/laws/lawsdigest/flood.html |title=Flood Control Act of 1944 |publisher=U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |work=Digest of Federal Resource Laws of Interest to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.msaconline.com /Missouri%20River%20Basin%20Project%20-%20The%20System.htm |title=Missouri River Basin Project: The System |publisher=Missouri Sediment Action Coalition |year=2011 |

|||

|accessdate=2012-03-10}}</ref> The 1944 act authorized the [[Pick–Sloan Missouri Basin Program]] (Pick–Sloan Plan), which was a composite of two widely varying proposals. The Pick plan, with an emphasis on flood control and hydroelectric power, called for the construction of large storage dams along the main stem of the Missouri. The Sloan plan, which stressed the development of local irrigation, included provisions for roughly 85 smaller dams on tributaries. |

|||

This was met with controversy from inhabitants of the Yellowstone basin, and eventually the USBR proposed a solution: to greatly increase the size of the proposed dam at Riverdale – today's Garrison Dam, thus replacing the storage that would have been provided by the Yellowstone dams. Because of this decision, the Yellowstone is now the longest free-flowing river in the contiguous United States.<ref>{{cite web |author=Bon, Kevin W. |url=http://library.fws.gov/Wetlands/upperyellowstone_01.pdf |title=Upper Yellowstone River Mapping Project |publisher=U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |date=July 2001 |accessdate=2012-01-14}}</ref> In the 1950s, construction commenced on the five mainstem dams – Garrison, Oahe, [[Big Bend Dam|Big Bend]], [[Fort Randall Dam|Fort Randall]] and [[Gavins Point Dam|Gavins Point]] – proposed under the Pick-Sloan Plan.<ref name="Pick-Sloan"/> Along with Fort Peck, which was integrated as a unit of the Pick-Sloan Plan in the 1940s, these dams now form what is known as the Missouri River Mainstem System.<ref name="Mainstem">{{cite web |author=Knofczynski, Joel |url=http://dnr.ne.gov/MissouriRiverActivities/pdf_files /MissouriRiver_MainstemSystem-Nov2010.pdf |title=Missouri River Mainstem System 2010–2011 Draft Annual Operating Plan |publisher=Nebraska Department of Natural Resources |work=U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |date=November 2010 |accessdate=2011-01-12}}</ref> |

|||

Los seis presas del Mainstem System, principalmente Fort Peck, Garrison y Oahe, son algunas de las [[presas más grandes del mundo por volumen]]; sus extensos embalses también están entre los [[Anexo:Presas de Estados unidos|más grandes de la nación]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ussdams.org/uscold_s.html |title=Dam, Hydropower and Reservoir Statistics |publisher=United States Society on Dams |accessdate=2010-10-05}}</ref> La celebración de hasta 91,4 km3 en total, los seis embalses pueden almacenar un valor de flujo del río más de tres años de como se mide a continuación Gavins Point, . la presa inferior.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/> Esta enorme capacidad lo convierte en el sistema de almacenamiento más grande de Estados Unidos y uno de los más grandes en América del Norte.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.epa.gov/region07/citizens/care/missouri.htm |title=The Missouri River Mainstem |publisher=U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |date=2011-04-15 |accessdate=2012-01-15}}</ref> Además de almacenar agua de riego, el sistema también incluye una reserva anual de control de inundaciones de 20.1 km<sup>3</sup>.<ref name="Mainstem"/> Las centrales eléctricas en el cauce principal generan alrededor de 9,3 millones de kWh al año -igual a una salida constante de casi 1.100 [[megavatio]]s.<ref>{{cite news |author=MacPherson, James |url=http://news.yahoo.com/power-generation-missouri-river-dams-rebounds-182956078.html |title=Power generation at Missouri River dams rebounds |publisher=Yahoo! News |agency=Associated Press |date=2012-01-05 |accessdate=2012-01-14}}</ref> Junto con cerca de 100 presas más pequeñas en los afluentes, principalmente en el Bighorn, Platte , Kansas y Osage, el sistema proporciona agua de riego a cerca de {{unidad|19000|km2}} ( km2) de tierra.<ref name="Pick-Sloan" /><ref>{{cite news |last=Johnston |first=Paul |title=History of the Pick-Sloan Program |publisher=American Society of Civil Engineers |work=World Environmental and Water Resource Congress 2006 |url=http://cedb.asce.org/cgi/WWWdisplay.cgi?152895 |accessdate=2012-01-19}}</ref> |

|||

Holding up to 74.1 million acre-feet (91.4 km<sup>3</sup>) in total, the six reservoirs can store more than three year's worth of the river's flow as measured below Gavins Point, the lowermost dam.<ref name="MainstemSystem"/> |

|||

{| class="wikitable sortable collapsible collapsed" style="width:47%; float:left;" |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan=6|Presas en el río Misuri |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

!Presa |

|||

!Estado(s) |

|||

!Altura |

|||

!Embalse |

|||

!Capacidad<br>(Acre.ft) |

|||

!Capacidad<br>([[Megawatt|MW]]) |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

!scope="row" |[[Toston Dam|Toston]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dnrc.mt.gov/wrd/water_proj/factsheets/toston_factsheet.pdf|title=Toston Dam (Broadwater-Missouri)|publisher=Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation|work=Water Projects Bureau|accessdate=2011-03-16}}</ref> |

|||

|MT |

|||

|{{nts|56}} ft<br>(17 m) |

|||

| |

|||

|3,000 |

|||

| style="background:#eee8aa;"|10 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

!scope="row" |[[Canyon Ferry Dam|Canyon Ferry]]<ref name="CanyonFerryDam"/> |

|||

|MT |

|||

|{{nts|225}} ft<br>(69 m) |

|||

|[[Canyon Ferry Lake]] |

|||

|1,973,000 |

|||

|50 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

!scope="row" |[[Hauser Dam|Hauser]]<ref name="Hauser"/> |

|||

|MT |

|||

|{{nts|80}} ft<br>(24 m) |

|||

|[[Hauser Lake]] |

|||

|98,000 |

|||

|19 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

!scope="row" |[[Holter Dam|Holter]]<ref name="HolterDam"/> |

|||

|MT |

|||

|{{nts|124}} ft<br>(38 m) |

|||

|[[Holter Lake]] |

|||

|243,000 |

|||

|48 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

!scope="row" |[[Black Eagle Dam|Black Eagle]]<ref name="BlackEagleDam"/> |

|||

|MT |

|||

|{{nts|13}} ft<br>(4.0 m) |

|||

|Long Pool{{#tag:ref|"Long Pool" is the name used by area residents to refer to the smooth, almost lake-like {{convert|55|mi|km|abbr=on}} stretch of the Missouri between the Black Eagle Dam and the town of [[Cascade, Montana|Cascade]]. Only about {{convert|2|mi|km|abbr=on}} of the so-called Long Pool are actually part of the impoundment behind the dam.|group=n}} |

|||

|2,000 |

|||

| style="background:#eee8aa;"|21 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

!scope="row" |[[Rainbow Dam|Rainbow]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pplmontana.com/producing+power/power+plants/Rainbow+Dam.htm|title=Rainbow Dam|publisher=PPL Montana|work=Producing Power|accessdate=2011-03-16}}</ref> |

|||

|MT |

|||

|{{nts|29}} ft<br>(8.8 m) |

|||

| |

|||

|1,000 |

|||

| style="background:#eee8aa;"|36 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

!scope="row" |[[Cochrane Dam|Cochrane]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pplmontana.com/producing+power/power+plants/Cochrane+Dam.htm|title=Cochrane Dam|publisher=PPL Montana|work=Producing Power|accessdate=2011-03-16}}</ref> |

|||

|MT |

|||

|{{nts|59}} ft<br>(18 m) |

|||

| |

|||

|3,000 |

|||

| style="background:#eee8aa;"|64 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

!scope="row" |[[Ryan Dam|Ryan]]<ref name="RyanDam"/> |

|||

|MT |

|||

|{{nts|61}} ft<br>(19 m) |

|||

| |

|||

|5,000 |

|||

| style="background:#eee8aa;"|60 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

!scope="row" |[[Morony Dam|Morony]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pplmontana.com/producing+power/power+plants/Morony+Dam.htm|title=Morony Dam|publisher=PPL Montana|work=Producing Power|accessdate=2011-03-16}}</ref> |

|||

|MT |

|||

|{{nts|59}} ft<br>(18 m) |

|||

| |

|||

|3,000 |

|||

| style="background:#eee8aa;"|48 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

! scope="row" style="background:#7fffd4;"|[[Fort Peck Dam|Fort Peck]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nwo.usace.army.mil/lake_proj/fortpeck/index.html|title=Fort Peck Dam/Fort Peck Lake|publisher=U.S. Army Corps of Engineers|work=Omaha District|accessdate=2011-03-16}}</ref> |

|||

|MT |

|||

|{{nts|250}} ft<br>(76 m) |

|||

|[[Fort Peck Lake]] |

|||

|18,690,000 |

|||

|185 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

! scope="row" style="background:#7fffd4;"|[[Garrison Dam|Garrison]]<ref>{{cite web|last=Wilson|first=Ron|url=http://gf.nd.gov/multimedia/ndoutdoors/issues/2003/jun/docs/garrison-dam.pdf|title=Garrison Dam: A Half-Century Later|publisher=North Dakota Game and Fish Department|work=ND Outdoors|date=June 2003|accessdate=2011-03-16|page=14}}</ref> |

|||

|ND |

|||

|{{nts|210}} ft<br>(64 m) |

|||

|[[Lake Sakakawea]] |

|||

|23,800,000 |

|||

|515 |

|||

|- style="font-size:9pt" |

|||

! scope="row" style="background:#7fffd4;"|[[Oahe Dam|Oahe]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nwo.usace.army.mil/lake_proj/MasterPlan/OaheMP.pdf|title=Final Oahe Dam/Lake Oahe Master Plan: Missouri River, South Dakota and North Dakota|publisher=U.S. Army Corps of Engineers|date=September 2010|accessdate=2012-01-17}}</ref> |

|||

|SD |

|||

|{{nts|245}} ft<br>(75 m) |

|||

|[[Lake Oahe]] |