Diferencia entre revisiones de «Franklin D. Roosevelt»

jaja lo borre!!! |

Deshecha la edición 26436747 de Dañahistorias (disc.) |

||

| Línea 1: | Línea 1: | ||

{{Ficha de Presidente |

|||

jaja lo borre!!! |

|||

| nombre=Franklin Delano Roosevelt |

|||

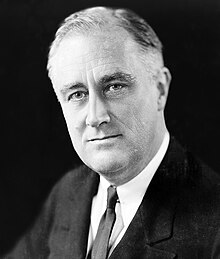

| imagen=FDR in 1933.jpg |

|||

| cargo='''32.º [[Presidente de los Estados Unidos]]''' |

|||

| inicio=[[4 de marzo]] de [[1933]] |

|||

| final=[[12 de abril]] de [[1945]] |

|||

| predecesor=[[Herbert C. Hoover]] |

|||

| sucesor=[[Harry S. Truman]] |

|||

| fechanac=[[30 de enero]] de [[1882]] |

|||

| lugarnac={{bandera|USA}} [[Hyde Park]], [[Nueva York]] |

|||

| fechamuerte=[[12 de abril]] de [[1945]] ({{edad|30|1|1882|12|4|1945}}) |

|||

| lugarmuerte=[[Warm Springs]], [[Georgia (Estados Unidos de América)|Georgia]] |

|||

| cónyuge=[[Eleanor Roosevelt|Anna Eleanor Roosevelt]] |

|||

| partido=[[Partido Demócrata de los Estados Unidos|Demócrata]] |

|||

| vicepresidente= |

|||

[[John N. Garner]] (1933-1941) |

|||

[[Henry A. Wallace]] (1941-1945) |

|||

[[Harry S Truman]] (1945) |

|||

| firma=Franklin_D._Roosevelt_signature.gif |

|||

| cargo2='''48.º [[Gobernador de Nueva York]]''' |

|||

| inicio2=[[1 de enero]] de [[1929]] |

|||

| final2=[[1 de enero]] de [[1933]] |

|||

| predecesor2=[[Alfred E. Smith]] |

|||

| sucesor2=[[Herbert H. Lehman]] |

|||

| religión=[[Iglesia Episcopal en los Estados Unidos de América|Episcopaliana]] |

|||

| almamáter=[[Universidad Harvard]] |

|||

| profesión=[[Abogado]] ([[Empresa]]) |

|||

|}} |

|||

'''Franklin Delano Roosevelt''' (Hyde Park ([[Nueva York]]), [[30 de enero]] de [[1882]] — [[Warm Springs]] ([[Georgia (Estados Unidos de América)|Georgia]]), [[12 de abril]] de [[1945]]) fue el trigésimo segundo [[Presidente de los Estados Unidos|Presidente]] de los [[Estados Unidos]] y ha sido el único en ganar cuatro elecciones presidenciales en esa nación. |

|||

== Primeros años == |

|||

Franklin Delano Roosevelt nació el [[30 de enero]] de [[1882]], en Hyde Park, [[Nueva York]]. Su padre, [[James Roosevelt]] (1828–1900), era un adinerado terrateniente y vicepresidente del [[ferrocarril de Delaware y Hudson]]. La familia de Roosevelt (véase [[árbol de familia de Roosevelt]]) había vivido en Nueva York durante más de doscientos años: [[Claes van Rosenvelt]], originalmente de [[Haarlem]] en [[Países Bajos]], llegó a Nueva York (entonces llamada [[Nueva Amsterdam|Nieuw Amsterdam]]) hacia 1650. En 1788, [[Isaac Roosevelt]] era miembro de la [[convención del estado]] de [[Poughkeepsie, York|Poughkeepsie nuevo]] que votó para ratificar la [[constitución de Estados Unidos]], una cuestión que llenaba de orgullo a su descendiente Franklin. |

|||

En el siglo XVIII la familia Roosevelt se dividió en dos ramas, los "Roosevelts de Hyde Park", quienes a finales del siglo XIX eran el "Partido Demócrata de los Estados Unidos" o "Demócratas", y el "Oyster Bay, New York" o "Oyster Bay". El presidente [[Theodore Roosevelt]], un republicano del Oyster Bay, era el quinto primo de Franklin. A pesar de sus diferencias políticas, las dos ramas siguieron llevándose bien. James Roosevelt conoció a su esposa en una reunión de la familia Roosevelt en Oyster Bay, y Franklin se casó con la sobrina de Theodore. |

|||

La madre de Roosevelt, [[Sara Roosevelt|Sara Ann Delano]] (1854–1941) era descendiente de [[Phillippe de la Noye]], hijo de protestantes franceses [[hugonote]]s radicados en [[Leiden]] quien emigró en [[1621]] a [[Massachusetts]]. Ella era hija de Warren Delano cónsul de Estados Unidos en [[China]], razón por la que pasó su niñez en dicho país, en su viaje de regreso a Estados Unidos los Délano vivieron un tiempo en [[Valparaíso]] en casa de sus parientes de Chile. Su madre pertenecía a los [[Lyman]], otra familia de gran tradición en los [[Estados Unidos]]. Franklin fue su único hijo, y se convirtió en una madre extremadamente posesiva. Puesto que James era un padre ausente y muy mayor (tenía 54 años cuando nació Franklin), Sara fue la influencia dominante en los primeros años de Franklin. El mismo, mucho más tarde, indicó a sus amigos que durante toda su vida tuvo miedo de ella. |

|||

Roosevelt creció en una atmósfera privilegiada. Aprendió a montar a caballo, tiro, lucha y a jugar al [[polo]] y a [[tenis]]. Sus frecuentes viajes a [[Europa]] permitieron que pudiera hablar [[lengua alemana|alemán]] y [[lengua francesa|francés]]. No obstante, el hecho de que su padre fuera demócrata, le apartó de la mayoría de los miembros de la aristocracia de [[Hudson Valley]]. Los Roosevelt creían en el servicio público, y eran lo suficientemente ricos para emplear su tiempo y dinero en tareas filantrópicas. |

|||

Roosevelt acudió al [[Groton School]], una residencia de estudiantes de la [[Iglesia Episcopal en los Estados Unidos de América]] cercana a Boston. Estaba profundamente influido por su director, [[Endicott Peabody]] que predicaba el deber cristiano de ayudar a los menos afortunados y fomentaba que sus alumnos ingresaran en el servicio público. Roosevelt se graduó en Groton en [[1900]], y posteriormente ingresó en la [[Universidad Harvard]], donde estudió moda doméstica y se graduó en artes en 1904 sin muchos esfuerzos para estudiar. Mientras estaba en Harvard, [[Theodore Roosevelt]] se convirtió en Presidente, y su vigoroso estilo de gobierno y su celo reformista se convirtieron en el modelo de Franklin. En [[1903]], conoció a su futura mujer [[Eleanor Roosevelt]], sobrina de Theodore, en una recepción en la Casa Blanca (previamente se habían conocido como niños, pero éste fue su primer encuentro serio). |

|||

Posteriormente, Roosevelt acudió a la Facultad de Derecho de la [[Universidad Columbia]]. Pasó el [[bar exam]] y satisfizo los requisitos para graduarse en Derecho en [[1907]], pero finalmente no lo hizo. En [[1908]] comenzó a trabajar con Ledyard y Milburn, prestigiosa firma de Wall Street, donde ejerció fundamentalmente el derecho de sociedades. |

|||

== Matrimonio e hijos == |

|||

Pese a la fuerte oposición de Sara Delano Roosevelt, que no quería perder el control sobre Franklin, éste se casó con Eleanor el [[17 de marzo]] de [[1905]]. Se trasladaron a una casa comprada para ellos por Sara, que se convirtió en invitada habitual, para desgracia de Eleanor. Ésta era terriblemente tímida y odiaba la vida social y, al principio, sólo deseaba estar en casa y criar a los hijos de Franklin, los cuales fueron seis en una rápida sucesión: |

|||

*[[Anna E. Roosevelt|Anna Eleanor]] (1906–1975). |

|||

*[[James Roosevelt|James]] (1907–1991). |

|||

*[[Franklin Delano, Jr.]] (Marzo a Abril de 1909). |

|||

*[[Elliott Roosevelt|Elliott]] (1910–1990), |

|||

*un segundo [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jr.|Franklin Delano Jr.]] (1914–1988), |

|||

*[[John Aspiwall Roosevelt|John Aspiwall]] (1916–1981). |

|||

Todos los hijos supervivientes de los Roosevelt tuvieron vidas tumultuosas ensombrecidas por sus famosos padres. Entre todos ellos, tuvieron 15 matrimonios, 10 divorcios y 29 hijos. Todos los hijos fueron oficiales en la [[Segunda Guerra Mundial]] y fueron condecorados por sus meritos y valentía. Sus carreras posteriores a la Guerra, tanto en política como en los negocios, fueron un desastre (se evidenció que muchos de sus logros solo lo habían conseguido por su padre). Dos de ellos fueron brevemente elegidos para la [[Cámara de Representantes de los Estados Unidos]], pero ninguno llegó más alto, pese a numerosos intentos. Uno de ellos fue republicano. |

|||

== Carrera política == |

|||

[[Archivo:Franklin Roosevelt Secretary of the Navy 1913.jpg|thumb|right|200px|FDR como Secretario de Marina, en 1913]] |

|||

En 1910, Roosevelt se presentó como candidato para el Senado del [[Estado de Nueva York]], por el distrito de Hyde Park, el cual no había elegido un Demócrata desde [[1884]]. El apellido Roosevelt, el dinero Roosevelt y la corriente demócrata de ese año, le llevaron a la capital del Estado [[Albany (Nueva York)|Albany]], donde lideró un grupo de reformistas que se opusieron a la maquinaria de Manhattan de [[Tammany Hall]] que dominaba al Partido Demócrata del estado. Roosevelt era joven (30 años en 1912), alto, bien parecido y bien hablado, y pronto se convirtió en una figura dentro de los Demócratas de Nueva York. Cuando [[Woodrow Wilson]] fue elegido Presidente en 1912, Roosevelt asumió el cargo de Secretario Adjunto del Ejército. En 1914, se presentó a la elección demócrata para el [[Senado de los Estados Unidos]], pero fue duramente derrotado en las primarias por Tammany Hall-BAcked [[James W. Gerard]]. |

|||

Entre 1913 y 1917, Roosevelt trabajó para expandir el Ejército (con la importante oposición de los pacifistas de la Administración, como por ejemplo el Secretario de Estado [[William Jennings Bryan]]), y fundó la [[Reserva del Ejército de los Estados Unidos]], para proporcionar una reserva de hombres entrenados para ser movilizados en tiempos de guerra. Wilson envió al Ejército y a los Marines a [[América Central]] y al [[Caribe]] para que intervinieran en países de dichas zonas. Roosevelt redactó en persona la Constitución de [[Haití]] de 1915, impuesta por los Estados Unidos. Cuando los Estados Unidos entraron en la [[Primera Guerra Mundial]], en abril de 1917, Roosevelt se convirtió en el más alto administrador del [[Ejército de los Estados Unidos]], ya que el [[Secretario del Ejército]], [[Josephus Daniels]], había sido elegido por razones políticas y tan sólo desempeñaba funciones representativas. |

|||

Roosevelt desarrolló un afecto por el Ejército para toda la vida. Demostró un gran talento administrativo y rápidamente aprendió a negociar con los líderes congresistas y otros departamentos gubernamentales para aprobar presupuestos y conseguir una rápida expansión del Ejército. Se convirtió en un firme defensor del [[submarino]] y de las formas para combatir la amenaza de los submarinos alemanes a la flota Aliada: propuso crear una barrera de minas a través del [[Mar del Norte]] desde [[Noruega]] a [[Escocia]]. En 1918, visitó [[Inglaterra]] y [[Francia]] para inspeccionar las instalaciones navales estadounidenses — en esa visita coincidió con [[Winston Churchill]] por primera vez. Con el fin de la guerra en noviembre de 1918, se encargó de la desmovilización, aunque se opuso al completo desmantelamiento del Ejército. |

|||

En 1920, la [[Convención Demócrata Nacional]] le eligió como candidato a Vicepresidente de los Estados Unidos en la candidatura encabezada por el Gobernador de Ohio, James M. Cox. Los oponentes republicanos denunciaron los ocho años de falta de gestión y pidieron un [["Retorno a la Normalización"]]. La candidatura Cox-Roosevelt fue ampliamente derrotada por el republicano [[Warren Harding]]. Entonces, Roosevelt se retiró de la práctica legal en Nueva York, pero pocos dudaron que pronto volvería a la carrera política de nuevo. |

|||

== Vida privada == |

|||

Roosevelt era un hombre carismático, bien parecido y activo socialmente, mientras que su mujer Eleanor era tímida y retraída, más aún teniendo en cuenta que prácticamente estuvo embarazada durante toda la década posterior a 1906. Roosevelt encontró pronto amantes fuera de su matrimonio. Una de ellas fue la secretaria social de Eleanor, [[Lucy Mercer]], con quien Roosevelt comenzó una relación al poco tiempo de ser contratada a principios de 1914. |

|||

En septiembre de 1918, Eleanor encontró cartas en el equipaje de Franklin que revelaron la infidelidad. Se enfureció y entristeció al mismo tiempo, enseñándole las cartas y demandando el divorcio. La madre de Franklin, Sara Roosevelt se enteró rápidamente de la crisis e intervino de forma decisiva. Argumentó que un divorcio arruinaría la carrera política de Franklin y apuntó que si Eleanor se divorciaba de Franklin, tendría que criar a cinco hijos ella sola. Dado que Sara financiaba a la pareja, es comprensible que este hecho fuera decisivo para evitar la ruptura del matrimonio. |

|||

Se alcanzó un acuerdo en el que se mantendría una apariencia de matrimonio, pero las relaciones sexuales cesaron. Sara pagaría una casa separada para Eleanor en Hyde Park y financiaría, así mismo, las actividades de beneficencia de Eleanor. Cuando Franklin se convirtió en Presidente—de lo que Sara siempre estuvo convencida—Eleanor sería capaz de usar su influencia para llevar a cabo sus actos de beneficencia. Eleanor aceptó estos términos y desde entonces, Franklin y Eleanor llevaron una nueva relación como amigos y colegas políticos, pero manteniendo vidas separadas. Franklin continuó viéndose con varias mujeres, incluida su secretaria Missy LeHand. |

|||

En agosto de 1921, mientras la familia Roosevelt estaba de vacaciones en la isla de Campobello, [[New Brunswick]], Franklin enfermó con [[poliomielitis]], una infección viral de las fibras nerviosas de la [[columna vertebral]], que probablemente contrajo nadando en el agua estancada de un lago cercano. El resultado fue que Roosevelt se quedó total y permanentemente paralizado de cintura para abajo. Al principio, los músculos de su abdomen y la parte más baja de la espalda también se vieron afectados, pero más tarde se recuperaron. De esta forma, podía levantarse y, con la ayuda de muletas, mantenerse de pie, pero no podía andar. Al contrario que en otras formas de paraplejia, sus intestinos, vejiga y funciones sexuales no se vieron afectadas. |

|||

Pese a que la parálisis por la polio no tenía cura (y, actualmente, sigue sin tenerla aunque es muy rara la infección por esta enfermedad en países desarrollados), Roosevelt rechazó durante toda su vida que estaría permanentemente paralizado. Probó con numerosos tratamientos, pero ninguno tuvo ningún efecto. No obstante, estaba convencido de los beneficios de la [[hidroterapia]] y, en 1926, compró un resort en [[Warm Springs]], [[Georgia (Estados Unidos de América)|Georgia]], donde fundó un centro de hidroterapia para tratar a los pacientes infectados por la polio, el cual continúa abierto y se llama [[Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation]] (con un objetivo aún más extenso) donde pasó mucho tiempo durante la década de los 20. Esto lo hizo en parte para escapar de su madre, la cual trató de recuperar el control sobre su vida mediante el seguimiento de su enfermedad. |

|||

En una época en que las intromisiones de la prensa en la vida privada de personajes públicos era mucho menos intensa que hoy en día, Roosevelt fue capaz de convencer a mucha gente de que estaba recuperándose, lo que pensaba que era esencial para retornar a la política. (La [[Enciclopedia Británica]], por ejemplo, dice que "por medio de cuidadosos ejercicios y tratamiento en Warm Springs, está recuperándose paulatinamente", aunque esto no fue cierto en absoluto.) Sujetando sus piernas y caderas por medio de abrazaderas de hierro, aprendió a caminar distancias cortas girando su torso mientras se apoyaba con un bastón. Usaba silla de ruedas en la intimidad, pero se cuidó mucho de no ser visto en público con ella, aunque en ocasiones apareció con muletas. Normalmente se mostraba de pie, mientras se apoyaba en un lado sobre uno de sus hijos. Pese a lo poco que le gustaba verse así, su estatua en silla de ruedas fue instalada en el [[Monumento a Franklin Delano Roosevelt]] en la ciudad de [[Washington, D.C.|Washington]]. |

|||

== Gobernador del Estado de Nueva York: 1928-1932 == |

|||

En torno a 1928 Roosevelt pensó que ya estaba plenamente recuperado como para relanzar su carrera política. Durante todo el tiempo que duró su retiro, se encargó de mantener sus contactos dentro del Partido Demócrata. |

|||

Asistió en 1924 a la Convención Demócrata e hizo un discurso de apoyo a la candidatura para la presidencia en favor del gobernador de Nueva York, [[Alfred E. Smith]]. Aunque Smith no fue elegido, volvió a optar de nuevo en 1928 y en esta ocasión también contó con el apoyo de Roosevelt. |

|||

Esta vez lo consiguió, proponiéndole a Roosevelt que optara a ser Gobernador de Nueva York. Para conseguir su nombramiento como candidato, Roosevelt tuvo que hacer las paces con [[Tammany Hall]], lo que hizo con grandes reparos. |

|||

En las elecciones de noviembre, Smith fue ampliamente derrotado por el republicano [[Herbert Hoover]], pero Roosevelt fue elegido Gobernador por un margen de 25.000 votos en una participación de 2,2 millones. Nacido al norte del Estado de Nueva York, tuvo más facilidad para ganar el voto de los residentes del Estado que no vivían en la ciudad de Nueva York con mucha más ventaja que otros candidatos demócratas. |

|||

<!-- |

|||

Roosevelt came to office in 1929 as a reform Democrat, but with no overall plan for his administration. He tackled official corruption by dismissing Smith's cronies and instituting a Public Service Commission, and took action to address New York's growing need for power through the development of [[hydroelectricity]] on the [[St. Lawrence River]]. He reformed the state's [[prison]] administration and built a new state prison at [[Attica, New York|Attica]]. He had a long feud with [[Robert Moses]], the state's most powerful public servant, whom he removed as Secretary of State but kept on as Parks Commissioner and head of [[urban planning]]. When the [[Wall Street Crash 1929|Wall Street Crash]] in October ushered in the [[Great Depression]], Roosevelt started a relief system that became the model for the [[New Deal]]. Roosevelt followed President [[Herbert Hoover]]'s advice and asked the state legislature for $20 million in relief funds, which he spent mainly on public works in the hope of stimulating demand and providing employment. Aid to the unemployed, he said, "must be extended by Government, not as a matter of charity, but as a matter of social duty." |

|||

Roosevelt knew little about economics, but he took advice from leading academics and social workers, and also from Eleanor, who had developed a network of friends in the welfare and labor fields and who took a close interest in social questions. On Eleanor's recommendation he appointed one of her friends, [[Frances Perkins]], as Labor Secretary, and there was a sweeping reform of the labor laws. He established the first state relief agency under [[Harry Hopkins]], who became a key advisor, and urged the legislature to pass an old age pension bill and an unemployment insurance bill. |

|||

The main weakness of the Roosevelt administration was the blatant corruption of the [[Tammany Hall]] machine in [[New York City]], where the Mayor, [[Jimmy Walker]], was the puppet of Tammany boss [[John F. Curry]], and where corruption of all kinds was rife. Roosevelt had made his name as an opponent of Tammany, but he needed the machine's goodwill to be re-elected in 1930 and for a possible future presidential bid. Roosevelt fell back on the line that the Governor could not interfere in the government of New York City. But as the 1930 election approached Roosevelt acted by setting up a judicial investigation into the corrupt sale of offices. This eventually resulted in Walker resigning and fleeing to [[Europe]] to escape prosecution. But [[Tammany Hall]]'s power was not seriously affected. In 1930 Roosevelt was elected to a second term by a margin of more than 700,000 votes. |

|||

==Election as President== |

|||

Roosevelt's immense popularity in the largest state in the country made him an obvious candidate for the Democratic nomination, which was hotly contested since it seemed clear that Hoover would be defeated at the [[U.S. presidential election, 1932|1932 presidential election]]. Al Smith also wanted the nomination, and Roosevelt was at first reluctant to oppose his old patrón. Roosevelt built an anti-Smith coalition using allies such as newspaper magnate [[William Randolph Hearst]], Irish leader [[Joseph P. Kennedy]], and Texas leader [[John Nance Garner]], who was give the vice presidential nomination. |

|||

The election campaign was conducted under the shadow of the [[Great Depression]]. The prohibition issue solidified the wet vote for Roosevelt, who noted that repeal would bring in new tax revenues. During the campaign Roosevelt said: "I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a [[New Deal|new deal]] for the American people", coining a eslogan that was later adopted for his legislative program. Roosevelt did not put forward and clear alternative to the policies of the Hoover Administration, but nevertheless won 57 percent of the vote and carried all but six states. During the long interregnum, Roosevelt refused Hoover's requests for a meeting to come up with a joint program to stop the downward spiral. In February 1933, in [[Miami]] an unemployed bricklayer named [[Giuseppe Zangara]] fired five shots at Roosevelt, missing him but killing the Mayor of Chicago, [[Anton Cermak]]. Zangara, who was later executed, said he had shot at Roosevelt because "the capitalists killed my life." |

|||

When Roosevelt was inaugurated in March 1933 the U.S. was at the nadir of the worst depression in its history. Some 13 million people, a third of the workforce, were unemployed. Industrial production had fallen by more than half since 1929. In a country with few government social services, millions were living on the edge of starvation, and two million were homeless. The banking system seemed to be on the point of collapse. There were occasional outbreaks of violence, but most observers considered it remarkable that such an obvious breakdown of the capitalist system had not led to a rapid growth of [[socialism]], [[communism]], or [[fascism]] (as happened for example in [[Germany]]). Instead of adopting revolutionary solutions, the American people had turned to the Democrats and to a leader who had grown up in privilege. |

|||

Roosevelt indeed had few systematic economic beliefs. He saw the Depression as mainly a matter of confidence—people had stopped spending, investing and employing labor because they were afraid to do so. As he put it in his [[inaugural address]]: "the only thing we have to fear is fear itself." He therefore set out to restore confidence through a series of dramatic gestures. He called a "bank holiday" to prevent a threatened run on the banks and called an emergency session of Congress to stabilize the financial system. The [[Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation]] was created to guarantee the funds held in all banks in the [[Federal Reserve|Federal Reserve System]], and thus prevent runs and bank failures. Roosevelt's series of radio speeches known as [[Fireside Chats]] presented his proposals to the American public. |

|||

==The First New Deal== |

|||

During the first [[hundred days]] of his administration, Roosevelt used his enormous prestige and the sense of impending disaster to force a series of bills through Congress, establishing and funding various new government agencies. These included the [[Emergency Relief Administration]], which granted funds to the states for unemployment relief; the [[Works Progress Administration]] and the [[Civilian Conservation Corps]] to hire millions of unemployed to work on local projects; and the [[Agricultural Adjustment Administration]], with powers to increase farm prices and support struggling [[farmer]]s. |

|||

Following these emergency measures came the [[National Industrial Recovery Act]] which imposed an unprecedented amount of state regulation on industry, including fair practice codes and a guaranteed role for [[trade unions]], in exchange for the repeal of [[anti-trust]] laws and huge amounts of financial assistance as a stimulus to the economy. Later came one of the largest pieces of state industrial enterprise in American history, the [[Tennessee Valley Authority]], which built dams and power stations, controlled floods, and improved agriculture in one of the poorest parts of the country. The repeal of [[prohibition]] also provided stimulus to the economy, while eliminating a major source of corruption. |

|||

In 1934, retired Marine General [[Smedley Butler]], who was at the time a prominent left-wing speaker, reported that leading capitalists had invited him to lead a march on Washington, seize the government, and become their dictator. This alleged attempt was known as the "[[Business Plot]]." |

|||

==Second New Deal 1935-36== |

|||

After the 1934 Congressional elections, which gave the Democrats large majorities in both houses, there was a fresh surge of New Deal legislation, driven by the "[[brains trust]]" of young economists and social planners gathered in the [[White House]], including [[Raymond Moley]], [[Rexford Tugwell]] and [[Adolf Berle]] of [[Columbia University]], attorney [[Basil O'Connor]], economist [[Bernard Baruch]] and [[Felix Frankfurter]] of [[Harvard Law School]]. Eleanor Roosevelt, Labor Secretary [[Frances Perkins]] (the first female Cabinet Secretary) and Agriculture Secretary [[Henry A. Wallace]] were also important influences. These measures included bills to regulate the [[stock market]] and prevent the corrupt practices which had led to the 1929 Crash; the [[Social Security Act]], which established [[Social Security (United States)|Social Security]] and promised economic security for the elderly, the poor and the sick; and the [[National Labor Relations Act]], which established the rights of workers to organice [[trade union|labor unions]], to engage in [[collective bargaining]] and to take part in [[strike action|strikes]] in support of their demands. |

|||

The net effect of these measures was to restore confidence and optimism, allowing the country to begin the long process of recovery from the Depression. The popular belief is that Roosevelt's programs, collectively known as the New Deal, cured the Great Depression. Historians and economists debate over the extent to which this is true. The New Deal ran up large deficits and in a sense it implemented the economic theories of [[John Maynard Keynes]], who advocated an interventionist government policy using fiscal measures to mitigate the [[depression (economics)|depression]]. It is unclear whether Roosevelt was influenced by these theories directly, and questionable whether he really understood them - although some of his advisers did. After a meeting with Keynes, who kept drawing diagrams, he remarked that "He must be a mathematician rather than a political economist." |

|||

The extent to which the large appropriations that Roosevelt extracted from Congress and spent on relief and assistance to industry provided a sufficient fiscal stimulus to revive the U.S. economy is also debated. The economy recovered significantly during Roosevelt's first term, but fell back into recession in 1937 and 1938 before making another recovery in 1939. While [[Gross National Product]] had surpassed its 1929 peak by 1940, [[unemployment]] remained about 15%. Some economists said there was a permanent structural unemployment. Others blamed the high tariff barriers that many countries had erected in response to the Depression, although foreign trade was not as important to the U.S. economy as it is today. The economy did start to grow after 1940 or 1941, but many simultaneous programs were involved, such as massive spending, price controls, bond campaigns, controls over raw materials, prohibitions on new housing and new automobiles, rationing, guaranteed cost-plus profits, subsidized wages, and the draft of 12 million soldiers. |

|||

==The second term== |

|||

[[Image:FDR0415.JPG|right|frame|Roosevelt's ebullient public personality did a great deal to help restore the nation's confidence.]] |

|||

In the [[U.S. presidential election, 1936|1936 presidential election]], Roosevelt campaigned on his New Deal programs against [[Kansas]] governor [[Alfred Landon]], who accepted much of the New Deal but objected that it was hostile to business and involved too much waste. Roosevelt and Garner won 61 percent of the vote and carried every state except [[Maine]] and [[Vermont]]. The New Deal Democrats won enough seats in Congress to outvote both the Republicans and the conservative Southern Democrats (who supported programs which brought benefits for their states but opposed measures which strengthened labor unions). Roosevelt was backed by a coalition of voters which included traditional Democrats across the country, small farmers, the "[[Solid South]]", Catholics, big city machines, labor unions, northern [[African-American]]s, [[Jews]], [[intellectuals]] and political liberals. This coalition, frequently referred to as the [[New Deal coalition]], remained largely intact for the Democratic Party until the 1960s. The Roosevelt ascendancy also prevented the growth of both [[communism]] and [[fascism]]. |

|||

Roosevelt's second term agenda included an act creating the [[United States Housing Authority]] (1937), a second Agricultural Adjustment Act and the [[Fair Labor Standards Act]] of 1938, which created the [[minimum wage]]. When the economy began to deteriorate again in late 1937, Roosevelt responded with an aggressive program of stimulation, asking Congress for $5 billion for relief and [[public works]] programs. |

|||

With the Republicans powerless in Congress, the conservative majority on the [[United States Supreme Court]] was the only obstacle to Roosevelt's programs. During 1935 the Court ruled that the [[National Recovery Act]] and some other pieces of New Deal legislation were [[unconstitutional]]. Roosevelt's response was to propose enlarging the Court so that he could appoint more sympathetic judges. This "[[court packing]]" plan was the first Roosevelt scheme to run into serious political opposition, since it seemed to upset the [[separation of powers]] which is one of the cornerstones of the American constitutional structure. Eventually Roosevelt was forced to abandon the plan, but the Court also drew back from confrontation with the administration by finding the Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act to be constitutional. Deaths and retirements on the Supreme Court soon allowed Roosevelt to make his own appointments to the bench. Between 1937 and 1941 he appointed eight justices to the court, including liberals such as [[Felix Frankfurter]], [[Hugo Black]] and [[William O. Douglas]], reducing the possibility of further clashes. |

|||

==Foreign policy 1933-41== |

|||

The rejection of the [[League of Nations]] treaty in 1919 marked the dominance of [[isolationism]] in American foreign policy. Despite Roosevelt's Wilsonian background, he and his Secretary of State, [[Cordell Hull]], acted with great care not to provoke isolationist sentiment. The main foreign policy initiative of Roosevelt's first term was the [[Good Neighbor Policy]], a re-evaluation of American policy towards [[Latin America]], which ever since the [[Monroe Doctrine]] of [[1823]] had been seen as an American [[sphere of influence]]. American forces were withdrawn from [[Haiti]], and new treaties with [[Cuba]] and [[Panama]] ended their status as American [[protectorate]]s. At the [[Seventh International Conference of American States]] in [[Montevideo]] in December 1933, Roosevelt and Hull signed the [[Montevideo Convention]] on the Rights and Duties of States, renouncing the assumed American right to intervene unilaterally in the affairs of Latin American countries. Nevertheless, the realities of American support for various Latin American [[dictator]]s, often to serve American corporate interests, remained unchanged. It was Roosevelt who made the often-quoted remark about the dictator of [[Nicaragua]], [[Anastasio Somoza]]: "Somoza may be a son of a bitch, but he's our son of a bitch." |

|||

Meanwhile, the rise to power of [[Adolf Hitler]] in Germany aroused fears of a new world war. In 1935, at the time of [[Italy]]'s invasion of [[Ethiopia|Abyssinia]], Congress passed the [[Neutrality Act]], applying a mandatory ban on the shipment of arms from the U.S. to any combatant nation. Roosevelt opposed the act on the grounds that it penalized the victims of aggression such as Abyssinia, and that it restricted his right as President to assist friendly countries, but he eventually signed it. In 1937 Congress passed an even more stringent Act, but when the [[Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945)|Sino-Japanese War]] broke out in 1937 Roosevelt found various ways to assist [[China]], and warned that [[Italy]], [[Nazi Germany]] and [[Empire of Japan|Imperial Japan]] were threats to world peace and to the U.S. When [[World War II]] in [[Europe]] broke out in 1939, Roosevelt became increasingly eager to assist [[Britain]] and [[France]], and he began a regular secret correspondence with Winston Churchill, in which the two freely discussed ways of circumventing the Neutrality Acts. |

|||

In May 1940 Germany attacked France and rapidly occupied the country, leaving Britain vulnerable to German air attack and possible invasion. Roosevelt was determined to prevent this and sought to shift public opinion in favor of aiding Britain. He secretly aided a private body, the [[Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies]], and he appointed two anti-isolationist Republicans, [[Henry L. Stimson]] and [[Frank Knox]], as Secretaries of War and the Navy respectively. The fall of [[Paris]] shocked American opinion, and isolationist sentiment declined. In August, Roosevelt openly defied the Neutrality Acts with the [[Destroyers for Bases Agreement]], which gave 50 American [[destroyer]]s to Britain and [[Canada]] in exchange for base rights in the British Caribbean islands. This was a precursor of the March 1941 [[Lend-Lease]] agreement which began to direct massive military and economic aid to Britain. |

|||

==The path to war== |

|||

At the 1938 Congressional elections the Republicans staged their first comeback since 1932, gaining seats in both Houses and reducing Roosevelt's ability to pass legislation at will. Roosevelt's campaign to have conservative Democratic Senators such as [[Walter F. George]] of [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]] replaced by pro-Administration candidates was defeated. This increased speculation that Roosevelt would retire in 1940. No American President had ever sought a third term in office, following a precedent set by [[George Washington]]. During 1940, however, with the international situation growing increasingly threatening, Roosevelt decided that only he could lead the nation through the coming crisis. Republicans (and some others) said that this was a sign of his increasing arrogance. Nevertheless, Roosevelt's huge personal popularity allowed him to win the [[U.S. presidential election, 1940|1940 election]] with 55 percent of the vote and 38 of the 48 states, defeating Indiana lawyer [[Wendell Willkie]]. A shift to the left within the Administration was shown by the adoption of [[Henry A. Wallace]] as his Vice-President in place of the conservative Southerner John N. Garner. |

|||

Roosevelt's third term was dominated by World War II, first in Europe and then in the [[Pacific]]. Facing strong anti-war sentiment Roosevelt slowly began a re-armament in 1938. By 1940 it was in high gear, with bipartisan support, partly to expand and re-equip the [[United States Army]] and [[United States Navy|Navy]] and partly to become the "Arsenal of Democracy" supporting Britain, France, China and (after June 1941), the Soviet Union, From 1939, unemployment fell rapidly, as the unemployed either joined the armed forces or found work in arms factories. By 1941 there was a growing labor shortage in all the nation's major manufacturing centers, accelerating the [[Great Migration (African American)|Great Migration]] of African-American workers from the Southern states, and of underemployed farmers and workers from all rural areas and small towns. |

|||

Roosevelt turned for foreign policy advice to [[Harry Hopkins]]. They sought innovative ways to help Britain, whose financial resources were exhausted by the end of 1940. Congress, where isolationist sentiment was in retreat, passed the [[Lend-Lease Act]] in March 1941, allowing America to "lend" huge amounts of military equipment in return for "leases" on British naval bases in the Western Hemisphere. In sharp contrast to the loans of World War I, there would be no repayment after the war. Britain agreed to dismantle preferential trade arrangements that kept American exports out of the [[British Empire]]. This underlined the point that the war aims of the U.S. and Britain were not the same. Roosevelt was a lifelong [[free trade|free trader]] and anti-[[imperialist]], and ending European [[colonialism]] was one of his objectives. Roosevelt forged a close personal relationship with Churchill, who became British [[Prime Minister]] in May 1940. |

|||

When Germany invaded the [[Soviet Union]] in June 1941, Roosevelt extended Lend-Lease to the Soviets. During 1941 Roosevelt also agreed that the U.S. Navy would escort Allied convoys as far east as [[Iceland]], and would fire on German ships or submarines if they attacked Allied shipping within the U.S. Navy zone. Thus by mid-1941 Roosevelt had committed the U.S. to the Allied side with a policy of "all aid short of war." Roosevelt met with Churchill on [[August 14]], [[1941]] to develop the [[Atlantic Charter]] in what was to be the first of several [[List of World War II conferences|wartime conferences]]. |

|||

==Pearl Harbor== |

|||

[[Image:Franklin Roosevelt signing declaration of war against Japan December 1941.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Roosevelt signing the declaration of war against Japan, December 1941.]] |

|||

Roosevelt was less keen to involve the U.S. in the war developing in [[East Asia]], where Japan occupied [[French Indo-China]] in late 1940. He authorized increased aid to China, and in July 1941 he restricted the sales of oil and other strategic materials to Japan, but also continued negotiations with the Japanese government in the hope of averting war. Through 1941 the Japanese planned their attack on the western powers, including the U.S., while spinning out the negotiations in Washington. The "hawks" in the Administration, led by Stimson and Treasury Secretary [[Henry Morgenthau, Jr.|Henry Morgenthau]], were in favor of a tough policy towards Japan, but Roosevelt, emotionally committed to the war in Europe, refused to believe that Japan might attack the U.S. and favored continued negotiations. The U.S. Ambassador in [[Tokyo]], [[Joseph C. Grew]], passed on warnings about the planned attack on the American Pacific Fleet's base at [[Pearl Harbor]] in [[Hawaii]], but these were ignored by the [[State Department]]. |

|||

On [[7 December]] [[1941]] the Japanese [[attack on Pearl Harbor|attacked the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor]], damaging most of it and killing 3,000 American personnel. The American commanders at Pearl Harbor, Admiral [[Husband E. Kimmel]] and General [[Walter Short]], were taken completely by surprise, and were later made scapegoats for this disaster. The fault really lay with the [[War Department]] in Washington, which since August 1940 had been able to read the Japanese diplomatic codes and had thus been given ample warning of the inminencia of the attack (though not of its actual date). In later investigations, the War Department claimed that it had not passed warnings on to the commanders in Hawaii because its analysts refused to believe that the Japanese would really have the effrontery to attack the United States. |

|||

It has become a staple of postwar [[historical revisionism|revisionist]] history that Roosevelt knew about the planned attack on Pearl Harbor but did nothing to prevent it so that the U.S. could be brought into the war as a result of being attacked. There is no evidence to support this theory. [[Conspiracy theory|Conspiracy theorists]] cite a document known as the [[McCollum memo]], written by a Naval Intelligence officer in 1940 and declassified in 1994, as evidence that the Roosevelt administration actively sought to enter into a war with Japan. It has never been shown, however, that Roosevelt or his Cabinet saw this document or were aware of the arguments it contained, let alone adopted them. No reputable historian accepts such conspiracy theories, although they are repeatedly promoted in the media. |

|||

In fact it is clear that when the Cabinet met on [[5 December]], its members were not aware of the impending attack. The Cabinet discussed the mounting intelligence evidence that the Japanese were mobilizing for war. Navy Secretary Knox told the Cabinet of the decoded messages showing that the Japanese fleet was at sea, but stated his opinion that it was heading south to attack the British in [[Malaya]] and [[Singapore]], and to seize the oil resources of the [[Dutch East Indies]]. Roosevelt and the rest of the Cabinet seemed to accept this view. There were intercepted Japanese messages suggesting an attack on Pearl Harbor, but delays in translating and passing on these messages through the inefficient War Department bureaucracy meant that they did not reach the Cabinet before the attack took place. There is no evidence that Roosevelt was made aware of them. All contemporary accounts describe Roosevelt, Hull and Stimson as shocked and outraged when they heard news of the attack. |

|||

The Japanese took advantage of their pre-emptive destruction of most of the Pacific Fleet to rapidly occupy the [[Philippines]] and all the British and Dutch colonies in [[Southeast Asia]], taking [[Singapore]] in February 1942 and advancing through [[Burma]] to the borders of [[British India]] by May, thus cutting off the overland supply route to China. Isolationism evaporated overnight and the country united behind Roosevelt as a wartime leader. Despite the wave of anger that swept across the U.S. in the wake of Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt decided from the start that the defeat of Nazi Germany had to take priority. Germany played directly into Roosevelt's hands when it declared war against the USA on [[December 11]] which removed any meaningful opposition to "beating Hitler first." Roosevelt met with Churchill in late December and planned a broad alliance between the U.S., Britain, and the Soviet Union, with the objectives of, first, halting the German advances in the Soviet Union and in North Africa; second, launching an invasion of western Europe with the aim of crushing Nazi Germany between two fronts, and only third turning to the task of defeating Japan. |

|||

Although Roosevelt was constitutionally the [[Commander-in-Chief]] of the United States armed forces, he had never worn a uniform and he did not interfere in operational military matters in anything like the way Churchill did in Britain, let alone take direct command of the forces as [[Adolf Hitler]] and [[Joseph Stalin]] did. He placed great trust in the Army Chief of Staff, General [[George Marshall]], and later in his Supreme Commander in Europe, General [[Dwight Eisenhower]], and left almost all strategic and tactical decisions to them, within the broad framework for the conduct of the war decided by the Cabinet in agreement with the other Allied powers. He had less confidence in his commander in the Pacific, General [[Douglas MacArthur]], whom he rightly suspected of planning to run for President against him. But since the war in the Pacific was mainly a naval war, this did not greatly matter until later in the war. Given his close personal interest in the Navy, Roosevelt tended to intervene more in naval matters, but strong Navy commanders like Admirals [[Ernest King]] in the Atlantic theater and [[Chester Nimitz]] in the Pacific enjoyed his confidence. |

|||

==Japanese-American internment== |

|||

{{main|Japanese American internment}} |

|||

Following the outbreak of the Pacific War, Roosevelt came under immediate pressure to remove or intern the estimated 120,000 people of Japanese origin or descent living in [[California]], two-thirds of which were American-born, on the grounds that they were a threat to security. Pressure came from the Democratic [[Governor of California]] [[Culbert Olson]], the [[William Randolph Hearst|Hearst]] newspapers and General [[John L. DeWitt]], the U.S. Army Commander in California, whose simple attitude was that "a [[Jap]] is a Jap." Opponents of the suggestion were Interior Secretary [[Harold L. Ickes]], Attorney-General [[Francis Biddle]] and [[FBI]] Director [[J. Edgar Hoover]], who said that there was no evidence of [[Japanese-American]] involvement in espionage or sabotage. |

|||

On February 7, 1942 Biddle met with Roosevelt and set out the Justice Department's objections to the proposal. Roosevelt then ordered that a plan be drawn up to evacuate the Japanese-Americans from California in the event of a landing or air attacks on the West Coast by Japan, but not otherwise. But on [[February 11]] he met with Secretary of War Stimson, who persuaded him to approve an immediate evacuation. There was evidence of [[espionage]] on behalf of Japan in the U.S. before and }after [[Pearl Harbor]]; code-breakers decrypted messages to Japan from agents in [[North America]] and [[Hawaii]]. These [[Magic (cryptography)|MAGIC]] cables were kept secret from all but those with the highest clearance, such as Roosevelt, lest the Japanese discover the decryption and change their code. |

|||

Roosevelt also wanted the 140,000 Japanese-Americans in Hawaii deported to the mainland, but the territorial authorities, including the Army, objected on the grounds that they were indispensable to the Islands' economy; thus the plan was dropped. Japanese-Americans continued to serve in the U.S. armed forces throughout the war, although they were not employed in the Pacific theatre. (The [[442nd Regimental Combat Team]] was composed almost entirely of formerly interned Japanese-Americans and remains the most highly decorated unit in U.S. military history.) Conditions in the camps, in Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado, were tolerable by most accounts (and quite pleasant according to others), but detainees naturally resented being detained and there were repeated disturbances in the camps, which resulted in 15,000 people being interned in a higher-security center at [[Tule Lake, California]]. In 1944 the Supreme Court upheld the legality of the executive order, which remained in force until December of that year. |

|||

By contrast, there was no mass internment of German-Americans or Italian-Americans. Out of 60 million Americans of German descent, only 11,000, all German-born, were placed in internment camps. As well, about 4,000 German nationals were deported from Central American countries for internment in the U.S., because the U.S. felt that these countries lacked the capacity to deal with possible German espionage. |

|||

Interior Secretary Ickes lobbied Roosevelt through 1944 to release the Japanese-American internees, but Roosevelt did not act until after the November presidential election. A fight for Japanese-American civil rights would have meant a fight with influential Democrats, the Army, and the Hearst press and would have endangered Roosevelt's chances of winning California in 1944. Critics of Roosevelt's actions believe they were motivated in part by racism. In 1925 he had written about Japanese immigration: "Californians have properly objected on the sound basic grounds that Japanese immigrants are not capable of assimilation into the American population... Anyone who has traveled in the Far East knows that the mingling of Asiatic blood with European and American blood produces, in nine cases out of ten, the most unfortunate results." But when activating the 442nd RCT on February 1, 1943, Roosevelt said, "No loyal citizen of the United States should be denied the democratic right to exercise the responsibilities of his citizenship, regardless of his ancestry. The principle on which this country was founded and by which it has always been governed is that Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart; Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry." |

|||

==Civil rights and refugees== |

|||

Roosevelt's attitudes to race were also tested by the issue of African-American (or "[[Negro]]", to use the term of the time) service in the armed forces. The Democratic Party at this time was dominated by Southerners who were opposed to any concession to demands for racial equality. During the New Deal years, there had been a series of conflicts over whether African-Americans were eligible for the various government benefits and programs. Typically, the young idealists who ran the programs tried to make these benefits available regardless of race. Southern Governors or Congressmen would then complain to Roosevelt, who would to keep his party together intervene to uphold segregation. The [[Works Progress Administration]] and the [[Civilian Conservation Corps]], for example, segregated their work forces by race at Roosevelt's insistence after Southern governors protested at unemployed whites being required to work alongside blacks. Roosevelt's personal racial attitudes were conventional for his time and class. He was not a visceral racist, but he accepted the common stereotype of African-Americans (whom he had little personal contact) as lazy, if good-natured, children. He did little to advance civil rights, despite prodding from Eleanor and liberals in his Cabinet such as Frances Perkins. |

|||

Roosevelt explained his reluctance to support anti-[[lynching]] legislation in a conversation with [[Walter White]] of the [[NAACP]]. "I did not choose the tools with which I must work. Had I been permitted to choose then I would have selected quite different ones. But I've got to get legislation passed by Congress to save America. The Southerners by reason of the seniority rule in Congress are chairmen or occupy strategic places on most of the Senate and House committees. If I come out for the anti-lynching bill now, they will block every bill I ask Congress to pass to keep America from collapsing. I just can't take that risk." |

|||

The war brought the race issue to the forefront. The Army and Navy had been segregated since the [[American Civil War|Civil War]]. African-Americans in the Army served only in rear-echelon or service roles, the Navy was almost entirely white and the [[United States Marine Corps|Marine Corps]] wholly so. Neither the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, nor the Navy Secretary, Frank Knox, were Southerners (Stimson came from a [[New York]] [[abolitionist]] family), but they were aware that the officer corps of both services included many Southerners, and feared disturbances or even [[mutiny]] if integration of the armed forces were imposed. "Colored troops do very well under white officers," said Stimson, "but every time we try to lift them a little beyond where they can go, disaster and confusion follow." Knox was blunter: "In our history we don't take Negroes into a ship's company." |

|||

But by 1940 the African-American vote had shifted almost totally from Republican to Democrat, and African-American leaders like [[Walter White]] of the [[NAACP]] and [[T. Arnold Hill]] of the [[National Urban League|Urban League]] had become recognized as part of the Roosevelt coalition. In June 1941, at the urging of [[A. Philip Randolph]], the leading African-American trade unionist, Roosevelt signed an executive order establishing the [[Fair Employment Practice Commission]] and prohibiting [[discrimination]] by any government agency, including the armed forces. In practice the services, particularly the Navy and the Marines, found ways to evade this order — the Marine Corps remained all-white until 1943. In September 1942, at Eleanor's instigation, Roosevelt met with a delegation of African-American leaders, who demanded full integration into the forces, including the right to serve in combat roles and in the Navy, the Marine Corps and the [[United States Army Air Force]]. Roosevelt, with his usual desire to please everyone, agreed, but then did nothing to implement his promise. It was left to his successor, [[Harry S. Truman]], to fully desegregate the armed forces. |

|||

Roosevelt's complex attitudes to American [[Jew]]s were also ambivalent. Franklin's mother Sara shared the conventional anti-Semitic attitudes common among Americans at a time when Jewish immigrants were flooding into the U.S. and their children were advancing rapidly into the business and professional classes, the alarm of those already there. Roosevelt apparently inherited some of his mother's attitudes, and at times expressed them in private. Paradoxically some of his closest political associates, such as [[Felix Frankfurter]], [[Bernard Baruch]] and [[Samuel I. Rosenman]], were Jewish, and he happily cultivated the important Jewish vote in New York City. He appointed [[Henry Morgenthau, Jr.]] as the first Jewish [[Secretary of the Treasury]] and appointed Frankfurter to the Supreme Court. |

|||

During his first term Roosevelt condemned Hitler's persecution of German Jews, but said "this is not a governmental affair" and refused to make any public comment. As the Jewish exodus from Germany increased after 1937, Roosevelt was asked by American Jewish organizations and Congressmen to allow these refugees to settle in the U.S. At first he suggested that the Jewish refugees should be "resettled" elsewhere, and suggested [[Venezuela]], [[Ethiopia]] or [[West Africa]] — anywhere but the U.S. Morgenthau, Ickes and Eleanor pressed him to adopt a more generous policy but he was afraid of provoking the isolationists — men such as [[Charles Lindbergh]] who exploited anti-Semitism as a means of attacking Roosevelt's policies. In practice very few Jewish refugees came to the U.S. — only 22,000 German refugees were admitted in 1940, not all of them Jewish. The State Department official in charge of refugee issues, [[Breckinridge Long]], was a visceral anti-Semite who did everything he could to obstruct Jewish immigration. Despite frequent complaints, Roosevelt failed to remove him. |

|||

After 1942, when Roosevelt was made aware, by Rabbi [[Stephen Wise]], the Polish envoy [[Jan Karski]] and others, of the Nazi extermination of the Jews, he refused to allow any systematic attempt to rescue European Jewish refugees and bring them to the U.S. In May 1943 he wrote to Cordell Hull (whose wife was Jewish): "I do not think we can do other than strictly comply with the present immigration laws." In January 1944, however, Morgenthau succeeded in persuading Roosevelt to allow the creation of a [[War Refugee Board]] in the Treasury Department. This allowed an increasing number of Jews to enter the U.S. in 1944 and 1945. By this time, however, the European Jewish communities had already been largely destroyed in Hitler's [[Holocaust]]. |

|||

In any case after 1945 the focus of Jewish aspirations shifted from migration to the U.S. to settlement in [[Palestine (region)|Palestine]], where the [[Zionism|Zionist]] movement hoped to create a Jewish state. Roosevelt was also opposed to this idea. When he met King [[Ibn Saud]] of [[Saudi Arabia]] in February 1945, he assured him he did not support a Jewish state in Palestine. He suggested that since the Nazis had killed three million Polish Jews, there should now be plenty of room in Poland to resettle all the Jewish refugees. Roosevelt's attitudes towards Japanese-Americans, Blacks and Jews remain in striking contrast with the generosity of spirit he displayed, and the social liberalism he practiced in other realms. |

|||

==Strategy and diplomacy== |

|||

[[Image:Cairo conference.jpg|thumb|right|300px|[[Chiang Kai-shek]] of China, Roosevelt, and [[Winston Churchill]] of Britain at the [[Cairo Conference]] in 1943]] |

|||

As Churchill rightly saw, the entry of the U.S. into the war meant that the ultimate victory of the Allied powers was assured. Even though Britain was exhausted by the end of 1942, the alliance between the manpower of the Soviet Union and the industrial resources of the U.S. was bound to defeat Germany and Japan in the long run. But mobilizing those resources and deploying them effectively was a difficult task. The U.S. took the straightforward view that the quickest way to defeat Germany was to transport its army to Britain, invade France across the [[English Channel]] and attack Germany directly from the west, Churchill, wary of the huge casualties he feared this would entail, favored a more indirect approach, advancing northwards from the [[Mediterranean]], where the Allies were fully in control by early 1943, into either [[Italy]] or [[Greece]], and thus into central Europe. Churchill also saw this as a way of blocking the Soviet Union's advance into east and central Europe, a political issue which Roosevelt and his commanders refused to take into account. |

|||

Since the U.S. would be providing most of the manpower and funds, Roosevelt's views prevailed, and through 1942 and 1943 plans for a cross-Channel invasion were advanced. But Churchill succeeded in persuading Roosevelt to undertake the invasions of French [[Morocco]] and [[Algeria]] ([[Operation Torch]]) in November 1942, of [[Sicily]] ([[Operation Husky]]) in July 1943, and of Italy ([[Operation Avalanche]]) in September 1943). This entailed postponing the cross-Channel invasion from 1943 to 1944. Following the American defeat at [[Anzio]], however, the invasion of Italy became bogged down, and failed to meet Churchill's expectations. This undermined his opposition to the cross-Channel invasion ([[Operation Overlord]]), which finally took place in June 1944. Although most of France was quickly liberated, the Allies were blocked on the German border in the "[[Battle of the Bulge]]" in December 1944, and final victory over Germany was not achieved until May 1945, by which time the Soviet Union, as Churchill feared, had occupied all of eastern and central Europe as far west as the [[Elbe River]] in central Germany. |

|||

Meanwhile in the Pacific the Japanese advance reached its maximum extent by June 1942, when Japan sustained a major naval defeat at the hands of the U.S. at the [[Battle of Midway]]. The Japanese advance to the south and south-east was halted at the [[Battle of the Coral Sea]] in May 1942 and the [[Battle of Guadalcanal]] between August 1942 and February 1943. MacArthur and Nimitz then began a slow and costly progress through the Pacific islands, with the objective of gaining bases from which strategic air power could be brought to bear on Japan and from which Japan could ultimately be invaded. In the event, this did not prove necessary, because the almost simultaneous declaration of war on Japan by the Soviet Union and the use of the [[atomic bomb]] on Japanese cities brought about Japan's surrender in September 1945. |

|||

By late 1943 it was apparent that the Allies would ultimately defeat Nazi Germany, and it became increasingly important to make high-level political decisions about the course of the war and the postwar future of Europe. Roosevelt met with Churchill and the Chinese leader [[Chiang Kai-shek]] at the [[Cairo Conference]] in November 1943, and then went to [[Tehran]] to confer with Churchill and Stalin. At the [[Tehran Conference]] Roosevelt and Churchill told Stalin about the plan to invade France in 1944, and Roosevelt also discussed his plans for a postwar international organization. Stalin was pleased that the western Allies had abandoned any idea of moving into the [[Balkans]] or central Europe via Italy, and he went along with Roosevelt's plan for the [[United Nations]], which involved no costs to him. Stalin also agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan when Germany was defeated. At this time Churchill and Roosevelt were acutely aware of the huge and disproportionate sacrifices the Soviets were making on the eastern front while their invasion of France was still six months away, so they did not raise awkward political issues which did not require immediate solutions, such as the future of Germany and Eastern Europe. |

|||

By the beginning of 1945, however, with the Allied armies advancing into Germany, consideration of these issues could not be put off any longer. In February, Roosevelt, despite his steadily deteriorating health, traveled to [[Yalta]], in the Soviet [[Crimea]], to meet again with Stalin and Churchill. This meeting, the [[Yalta Conference]], is often portrayed as a decisive turning point in modern history, but in fact, most of the decisions made there were retrospective recognitions of realities which had already been established by force of arms. The decision of the western Allies to delay the invasion of France from 1943 to 1944 had allowed the Soviet Union to occupy all of eastern Europe, including [[Poland]], [[Romania]], [[Bulgaria]], [[Czechoslovakia]] and [[Hungary]], as well as eastern Germany. Since Stalin was in full control of these areas, there was little Roosevelt and Churchill could do to prevent him imposing his will on them, as he was rapidly doing by establishing [[Communist]]-controlled governments in all these countries. |

|||

Churchill, aware that Britain had gone to war in 1939 in defense of Polish independence, and also of his promises to the [[Polish government in exile]] in [[London]], did his best to insist that Stalin agree to the establishment of a non-Communist government and the holding of free elections in liberated Poland, although he was unwilling to confront Stalin over the issue of Poland's postwar frontiers, on which he considered the Polish position to be indefensible. But Roosevelt was not interested in having a fight with Stalin over Poland, for two reasons. The first was that he believed that Soviet support was essential for the projected invasion of Japan, in which the Allies ran the risk of huge casualties. He feared that if Stalin was provoked over Poland he might renege on his Tehran commitment to enter the war against Japan. The second was that he saw the [[United Nations]] as the ultimate solution to all postwar problems, and he feared the United Nations project would fail without Soviet cooperation. |

|||

==Death and posthumous reputation== |

|||

[[Image:Yalta Conference.jpg|300px|thumb|The "Big Three" Allied leaders at [[Yalta]]: Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin]] |

|||

Although Roosevelt was only 63 in 1945, his health had been in decline since at least 1940. The strain of his paralysis and the physical exertion needed to compensate for it for over 20 years had taken their toll, as had many years of stress and a lifetime of chain-smoking. He had been diagnosed with [[high blood pressure]] and long-term [[heart disease]], and was advised to modify his diet (though not to stop smoking). Had it not been for the war, he would certainly have retired at the [[U.S. presidential election, 1944|1944 election]], but under the circumstances both he and his advisors felt there was no alternative to his running for a fourth term. Aware of the risk that Roosevelt would die during his fourth term, the party regulars insisted that Henry Wallace, who was seen as too pro-Soviet, be dropped as Vice President. Roosevelt at first resisted but finally agreed to replace Wallace with the little known Senator [[Harry S. Truman]]. In the November elections Roosevelt and Truman won 53 percent of the vote and carried 36 states, against [[New York]] Governor [[Thomas Dewey]]. After the elections, [[Cordell Hull]], the longest-serving Secretary of State in American history, retired and was succeeded by [[Edward Stettinius Jr.]]. |

|||

After the Yalta conference relations between the western Allies and Stalin deteriorated rapidly, and so did Roosevelt's health. When he addressed Congress on his return from Yalta, many were shocked to see how old, thin and sick he looked. He spoke from his wheelchair, an unprecedented concession to his physical incapacity. But he was still mentally fully in command. "The Crimean Conference," he said firmly, "ought to spell the end of a system of unilateral action, the exclusive alliances, the spheres of influence, the balances of power, and all the other expedients that have been tried for centuries — and have always failed. We propose to substitute for all these, a universal organization in which all peace-loving nations will finally have a chance to join." Many in his audience doubted that the proposed United Nations would achieve these objectives, but there was no doubting the depth of Roosevelt's commitment to these ideals, which he had inherited from [[Woodrow Wilson]]. |

|||

Roosevelt is often accused of being naively trusting of Stalin, but in the last months of the war he took an increasingly tough line. During March and early April he sent strongly worded messages to Stalin accusing him of breaking his Yalta commitments over Poland, Germany, [[prisoners of war]] and other issues. When Stalin accused the western Allies of plotting a separate peace with Hitler behind his back, Roosevelt replied: "I cannot avoid a feeling of bitter resentment towards your informers, whoever they are, for such vile misrepresentations of my actions or those of my trusted subordinates." |

|||

[[Image:Franklin Roosevelt funeral procession 1945.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Roosevelt's funeral procession.]] |

|||

On March 30, Roosevelt went to Warm Springs to rest before his anticipated appearance at the April 25 [[San Francisco]] founding conference of the United Nations. Among the guests was [[Lucy Page Mercer Rutherfurd|Lucy Mercer]], his lover from 30 years previously (by then Mrs. Lucy Rutherfurd), and the artist [[Elizabeth Shoumatoff]], who was painting a portrait of him. On the morning of [[April 12]] he was sitting in a leather chair signing letters, his legs propped up on a stool, while Shoumatoff worked at her easel. Just before lunch was to be served, he dropped his pen and complained of a sudden headache. Then he slumped forward in his chair and lost consciousness. A doctor was summoned and he was carried to bed; it was immediately obvious that he had suffered a massive [[cerebral hemorrhage]]. At 3:31 pm he was pronounced dead. The painting by Shoumatoff was not finished and is known as the [[Unfinished Portrait]]. |

|||

Roosevelt's death was greeted with shock and grief across the U.S. and around the world. At a time when the press did not pry into the health or private lives of Presidents, his declining health had not been known to the general public. Roosevelt had been President for more than 12 years, much longer than any other person, and had led the country through some of its greatest crises to the brink of its greatest triumph, the complete defeat of Nazi Germany, and to within sight of the defeat of Japan as well. Although in the decades since his death there have been many critical reassessments of his career, few commentators at the time had anything but praise for a commander-in-chief who had been robbed by death of a victory which was only a few weeks away. On [[May 8]], the new president, [[Harry S. Truman]], dedicated V-E Day to Roosevelt's memory, paying tribute to his commitment towards ending the war in Europe. |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||

Roosevelt's legacies to the U.S. were a greatly expanded role for government in the management of the economy (effectively ending the days of ''[[laissez-faire]]'' economics), increased government regulation of companies to protect the environment and prevent corruption, a Social Security system which allowed senior citizens to be able to retire with income and benefits, a nation on the winning side of World War II (with a booming wartime economy), and a coalition of voters supporting the Democratic Party which would survive intact until the 1960s and in part until the 1980s, when it was finally shattered by [[Ronald Reagan]], a Roosevelt Democrat in his youth who became a conservative Republican. Internationally, Roosevelt's monument was the United Nations, an organization which offered at least his hope of an end to the international anarchy which led to two world wars in his lifetime. |

|||

Majority support for the essentials of the Roosevelt domestic program survived their author by 35 years. The Republican administrations of [[Dwight Eisenhower]] and [[Richard Nixon]] did nothing to overturn the Roosevelt-era social programs. It was not until the administration of Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) that this was reversed, although Reagan made clear that though he wanted to greatly scale back many of FDR's programs, he would keep them intact (especially Social Security). [[Bill Clinton]], with his program of [[welfare reform]], was the first Democratic president to repudiate elements of the Roosevelt program. Nevertheless, this has not undermined Roosevelt's posthumous reputation as a great president. A 1999 survey of academic historians by [[CSPAN]] found that historians consider [[Abraham Lincoln]], [[George Washington]], and Roosevelt the three greatest presidents by a wide margin.[http://www.americanpresidents.org/survey/historians/performance.asp]. A 2000 survey by ''[[The Washington Post]]'' found Washington, Lincoln, and Roosevelt to be the only "great" Presidents. |

|||

==Cabinet members== |

|||

{| cellpadding="1" cellspacing="4" style="margin:3px; border:3px solid #000000;" align="left" |

|||

!bgcolor="#000000" colspan="3"| |

|||

|- |

|||

|align="left"|'''OFFICE'''||align="left"|'''NAME'''||align="left"|'''TERM''' |

|||

|- |

|||

!bgcolor="#000000" colspan="3"| |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[President of the United States|President]] || '''[[Franklin D. Roosevelt]]''' || 1933-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Vice President of the United States|Vice President]] || '''[[John Nance Garner]]''' || 1933-1941 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Henry A. Wallace]]''' || 1941-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Harry S. Truman]]''' || 1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

!bgcolor="#000000" colspan="3"| |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[United States Secretary of State|State]] || '''[[Cordell Hull]]''' || 1933-1944 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Edward Stettinius, Jr.|Edward R. Stettinius, Jr.]]''' || 1944-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[United States Secretary of War|War]] || '''[[George Dern|George H. Dern]]''' || 1933-1936 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Harry Hines Woodring|Harry H. Woodring]]''' || 1936-1940 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Henry L. Stimson]]''' || 1940-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[United States Secretary of the Treasury|Treasury]] || '''[[William Hartman Woodin|William H. Woodin]]''' || 1933-1934 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Henry Morgenthau, Jr.]]''' || 1934-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Attorney General of the United States|Justice]] || '''[[Homer Stille Cummings|Homer S. Cummings]]''' || 1933-1939 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Frank Murphy|William F. Murphy]]''' || 1939-1940 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Robert H. Jackson]]''' || 1940-1941 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Francis Biddle|Francis B. Biddle]]''' || 1941-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[United States Postmaster General|Post]] || '''[[James Farley|James A. Farley]]''' || 1933-1940 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Frank Comerford Walker|Frank C. Walker]]''' || 1940-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[United States Secretary of the Navy|Navy]] || '''[[Claude A. Swanson]]''' || 1933-1939 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Charles Edison]]''' || 1940 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Frank Knox]]''' || 1940-1944 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[James Forrestal|James V. Forrestal]]''' || 1944-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[United States Secretary of the Interior|Interior]] || '''[[Harold L. Ickes]]''' || 1933-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[United States Secretary of Agriculture|Agriculture]] || '''[[Henry A. Wallace]]''' || 1933-1940 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Claude R. Wickard]]''' || 1940-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[United States Secretary of Commerce|Commerce]] || '''[[Daniel Calhoun Roper|Daniel C. Roper]]''' ||1933-1938 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Harry Hopkins|Harry L. Hopkins]]''' || 1939-1940 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Jesse Holman Jones|Jesse H. Jones]]''' || 1940-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

| || '''[[Henry A. Wallace]]''' || 1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[United States Secretary of Labor|Labor]] || '''[[Frances Perkins|Frances C. Perkins]]''' || 1933-1945 |

|||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

<br clear="all"> |

|||

==Supreme Court appointments== |

|||

*[[Hugo Black]] (AL) [[August 19]], [[1937]]-[[September 17]], [[1971]] |

|||

*[[Stanley Forman Reed]] (KY) [[January 31]], [[1938]]-[[February 25]], [[1957]] |

|||

*[[Felix Frankfurter]] (MA) [[January 30]], [[1939]]-[[August 28]], [[1962]] |

|||

*[[William O. Douglas]] (CT) [[April 17]], [[1939]]-[[November 12]], [[1975]] |

|||

*[[Frank Murphy]] (MI) [[February 5]], [[1940]]-[[July 19]], [[1949]] |

|||

*[[Harlan Fiske Stone]] (Chief Justice, NY) [[July 3]], [[1941]]-[[April 22]], [[1946]] |

|||

*[[James Francis Byrnes]] (SC) [[July 8]], [[1941]]-[[October 3]], [[1942]] |

|||

*[[Robert H. Jackson]] (NY) [[July 11]], [[1941]]-[[October 9]], [[1954]] |

|||

*[[Wiley Blount Rutledge]] (IA) [[February 15]], [[1943]]-[[September 10]], [[1949]] |

|||

President Roosevelt appointed nine Justices to the [[Supreme Court of the United States]], which, depending on one's point of view, either puts him in a tie with [[George Washington]], or one behind him. Washington appointed ten Justices, but appointed [[John Rutledge]] twice, and Rutledge's nomination was rejected by the Senate the second time. Rutledge had been serving on the court in the meantime, however. Between the appointment of Justice [[Robert H. Jackson]] in [[1941]] and Roosevelt's death in [[1945]], eight of the nine Supreme Court Justices were Roosevelt appointees, the only holdout being [[Herbert Hoover|Hoover]] appointee [[Owen Josephus Roberts]]. Thus, Roosevelt almost became the second president to appoint the entire Supreme Court. |

|||

In 1937, Roosevelt proposed the Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937 (called the [[Court-packing Bill]] by its opponents). The proposal gave the President the power to appoint an extra Supreme Court Justice for every sitting Justice over the age of 70. The bill died in Congress. |

|||

==Media== |

|||

{{multi-video start}} |

|||

{{multi-video item | |

|||

filename = FDR video montage.ogg| |

|||

title = FDR video montage| |

|||

description =Collection of video clips of the president. (7.2 [[Megabyte|MB]], [[ogg]]/[[Theora]] format). | |

|||

format = [[Theora]] |

|||

}} |

|||

{{multi-video end}} |

|||

{{multi-listen start}} |

|||

{{multi-listen item | |

|||

filename=Roosevelt Pearl Harbor.ogg| |

|||

title=FDR Pearl Harbor speech| |

|||

description=Speech given before Joint Session of Congress in entirety. (3.1 [[Megabyte|MB]], [[ogg]]/[[Vorbis]] format). | |

|||

format=[[Vorbis]] |

|||

}} |

|||

{{multi-listen end}} |

|||

{{multi-listen start}} |

|||

{{multi-listen item | |

|||

filename=Roosevelt Infamy.ogg| |

|||

title="A date which will live in infamy"| |

|||

description=Section of Pearl Harbor speech with famous phrase. (168 [[Kilobyte|KB]], [[ogg]]/[[Vorbis]] format). | |

|||

format=[[Vorbis]] |

|||

}} |

|||

{{multi-listen end}} |

|||

==Online resources== |

|||

*[http://www.potus.com/fdroosevelt.html#cabinet Franklin Delano Roosevelt Cabinet Members] |

|||

==Primary sources== |

|||

* [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=98754501 Cantril, Hadley and Mildred Strunk, eds. ''Public Opinion, 1935-1946'' (1951)], massive compilation of many public opinion polls from USA and elsewhere. |

|||

* Gallup, George Horace, ed. ''The Gallup Poll; Public Opinion, 1935-1971'' 3 vol (1972) summarizes results of each poll. |

|||

* [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=7896020 Loewenheim, Francis L. et al, eds. ''Roosevelt and Churchill: Their Secret Wartime Correspondence'' (1975)] |

|||

* Nixon, Edgar B. ed. ''Franklin D. Roosevelt and Foreign Affairs'' (3 vol 1969), covers 1933-37. 2nd series 1937-39 available on microfiche and in a 14 vol print edition at some academic libraries. |

|||

* Roosevelt, Franklin D.; Rosenman, Samuel Irving, ed. ''The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt'' (13 vol, 1938, 1945); public material only (no letters); covers 1928-1945. |

|||

*[http://www.lexisnexis.com/academic/2upa/Aph/fdrDocumentary.asp ''Documentary History of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration''] 20 vol. available in some large academic libraries. |

|||

* [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=57258861 Zevin, B. D. ed. ''Nothing to Fear: The Selected Addresses of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1932-1945'' (1946)] |

|||

==Scholarly secondary sources== |

|||

* [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=101379496 Beasley, Maurine, et al eds. ''The Eleanor Roosevelt Encyclopedia'' (2001)] |

|||

* Black, Conrad. ''Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom'', Public Affairs, 2003. Strong popular biography |

|||

* Burns, James MacGregor. ''Roosevelt'' (1956, 1970), 2 vol; brilliant interpretive biography, emphasis on politics. |

|||

* Davis, Kenneth R. ''FDR: The Beckoning of Destiny, 1182-1928'' (1972), good popular biography. |

|||

* Freidel, Frank. ''Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Rendezvous with Destiny'' (1990), best one-volume scholarly biography; covers entire life |

|||