Usuario:Andycyca/Taller/Lista de obras designadas con la proporción áurea

Existen muchas obras de arte que, se supone, fueron diseñadas usando la proporción áurea. Sin embargo, varias de estas afirmaciones han sido discutidas o refutadas a través de la medición.[1]

El número áureo, un número irracional, es aproximadamente 1.618; a menudo se le denota con la letra griega φ (phi o fi).

Historia antigua[editar]

Varios autores han afirmado que hay monumentos antiguos con la proporción áurea, a menudo con interpretaciones basadas en conjeturas, usando medidas aproximadas y que sólo vagamente corresponden a 1.618.[1] Por ejemplo, existen afirmaciones acerca de proporciones áureas en vasijas de Egipto, Sumeria y Grecia, cerámicos de China, esculturas olmecas y productos de Creta y Micenas de la edad de bronce. Estos son al menos 1,000 años anteriores a los matemáticos griegos que estudiaron la razón áurea por primera vez.[2][3] Sin embargo, las fuentes históricas son oscuras y los análisis son difíciles de comparar, ya que usan diferentes metodologías.[2]

Se ha afirmado, por ejemplo, que Stonehenge (3100 a. C. – 2200 a. C.) tiene proporciones áureas entre sus círculos concéntricos.[2][4] Kimberly Elam ha propuesto esta relación como evidencia temprana de la preferencia cognitiva humana por la razón áurea.[5] Sin embargo, otros han señalado que esta interpretación de Stonehenge "puede ser dudosa" y que la construcción geométrica que la genera sólo puede ser objeto de conjeturas.[2] En otro ejemplo, Carlos Chanfón Olmos establece que la escultura del Rey Gudea (c. 2350 a. C.) tiene proporciones áureas entre todos los elementos secundarios repetidos en su base.[3]

La Gran Pirámide de Guiza (construida alrededor de 2570 a. C. por Heminuu) exhibe la razón áurea según ciertos piramidólogos, incluyendo a Charles Funck-Hellet.[3][6] John F. Pile, profesor de diseño de interiores e historiador, ha afirmado que los diseñadores egipcios conjeturaron las proporciones áureas sin técnicas matemáticas y que es común encontrar la razón 1.618:1, junto con muchos otros conceptos geométricos más sencillos, en sus detalles arquitectónicos, arte y objetos cotidianos encontrados en tumbas. En su opinión, "El que los egipcios conocieran [la razón áurea] y la usaran parece ser cierto."[7]

Aún antes de estas teorías, otros historiadores y matemáticos han propuesto teorías alternativas para los diseños de las pirámides que no están relacionados a ningún uso de la razón áurea y que, en su lugar, están basados en pendientes puramente racionales que sólo se aproximan a la razón áurea.[8] Los egipcios de aquella época aparentemente no conocían el teorema de Pitágoras; el único triángulo recto cuyas proporciones conocían era el triángulo con razón 3:4:5.[9]

Arquitectura antigua y medieval[editar]

Grecia[editar]

La Acrópolis de Atenas (468–430 a.C.), incluyendo al Partenón, según algunos estudios, tiene varias proporciones que se aproximan a la razón áurea.[10] Otros académicos se han cuestionado si la razón áurea fue conocida o usada por artistas y arquitectos griegos como principio de proporción estética.[11] Se ha calculado que la construcción de la Acrópolis comenzó alrededor de 600 a. C., pero las obras que se supone exhiben las poporciones doradas fueron creadas entre 468 y 430 a.C.

El partenón (447-432 a.C.) fue un templo dedicado a la diosa griega Atenea. Se ha afirmado que la fachada del Partenón, así como los elementos de la misma y en otros lados están circunscritos por una progresión de rectángulos dorados.[10] Algunos estudios más recientes disputan la visión que la razón áurea fue usada en el diseño.[1]

Hemenway afirma que el escultor griego Fidias (c. 480–c. 430 a.C.) usó las proporciones divinas en algunas de sus esculturas[12] Él creó Atenea Partenos en Atenas y Estatua de Zeus (una de las Siete maravillas del mundo antiguo) en Olimpia. Se cree que estuvo a cargo de otras esculturas del Partenón, aunque podrían haber sido ejecutadas por sus alumnos u otros escultores. A inicios del siglo xx, el matemático estadounidense Mark Barr propuso la letra griega Phi o Fi φ), la primera letra del nombre de Fidias, para denotar la razón áurea.[13]

Lothar Haselberger afirma que el templo de Apolo en Dídima (c. 334 a. C.), diseñado por Dafnis de Mileto y Peonio de Éfeso, tiene proporciones áureas.[3]

Arquitectura mesoamericana prehispánica[editar]

Entre 1950 y 1960, Manuel Amabilis aplicó algunos métodos de análisis desarrollados por Frederik Macody Lund y Jay Hambidge a los diseños de varios edificios prehispánicos, tales como El Toloc y La Iglesia de Las Monjas, un complejo notable de edificios del clásico terminal maya construidos en el estilo arquitectónico Puuc en Chichen Itzá. De acuerdo a sus estudios, sus proporciones se concretaron a partir de una serie de polígonos, círculos y pentagramas inscritos, tal y como Lund encontró en sus estudios de iglesias góticas. Manuel Amabilis publicó sus estudios, junto con varias imágenes evidentes de otros edificios precolombinos hechos con proporciones áureas, en La Arquitectura Precolombina de Mexico.[14] Dicha obra Esta obra recibió una medalla de oro y le valió a Amabilis el título de Académico por la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando en el concurso "Fiesta de la Raza" of 1929.[cita requerida]

El Templo de Kukulkán fue construido por la civilización maya entre los siglos xi y xiii y estaba dedicado, como indica su nombre, al dios Kukulkán. John Pile afirma que la disposición de su interior tiene proporciones de razón áurea. Pile también dice que las paredes interiores están dispuestas de tal forma que los espacios exteriores estén relacionados a la cámara central por la razón de oro[15]

Arquitectura Islámica[editar]

Se ha afirmado que la Gran Mezquita de Kairuán (construida en Uqba ibn Nafi c. 670 d. C.) usa la razón de oro en su diseño, incluyendo el plan, el espacio de oración, el patio y minaret,[Nota 1] pero la razón no aparece en las partes originales de la mezquita.[17]

Arquitectura budista[editar]

El Stupa de Borobudur en Java, Indonesia (construido entre los siglos viii y ix d.C.)— el stupa Budista más grande conocido— tiene la dimensión de la base cuadrada, en relación con el diámetro de la terraza circular más grande, como 1.618:1, de acuerdo con Pile.[18]

Arquitectura románica[editar]

El estilo de arquitectura románica prevaleció en Europa entre los siglos x y xiii, un período que termina con la transición hacia la {{arquitectura gótica]]. El contraste entre los conceptos románicos y góticos en los edificios religiosos pueden pueden entenderse en la correspondencia entre Bernardo de Caraval, cisterniense y el abad Suger de la orden de Clumy, el iniciador del arte gótico en Saint-Denis.

Una de las obras más bellas del cisterciense románico es la Abadía de Sénanque en Provenza, que fue fundada en 1148 y consagrada en 1178. Su construcción se inició durante la vida de Bernardo de Caraval. En La Lumière à Sénanque (La Luz en Sénanque),[19] (un capítulo de Cîteaux : commentarii cistercienses, publicación cisterniense) el autor Kim Lloveras i Montserrat, habla del estudio que hizo en 1992 sobre la iglecsia abacial y afirma que fue diseñada mediante un sistema de medidas basadas en la razóndorada, y que los instrumentos usados en su construcción fueron la “Vescica” y las escuadras medievales usadas por los constructores, ambas diseñadas con la razón áurea. La "Vescica" de Sénanque se encuentra en el claustro del monasterio, en el sitio del taller.

Arquitectura gótica[editar]

En su libro de 1919 Ad Quadratum, el historiador noruego Frederik Macody Lund, quien estudió la geometría de distintas estructuras góticas, afirma que la Catedral de Chartres (cuya construcción comenzó en el siglo xii), la Catedral de Laon (1157–1205), y Catredal de Notre Dame en París (1160) están diseñadas de acuerdo a la proporción áurea.[3] Otros académicos argumentan que no fue sino hasta la publicación de De Divina Proportione de Luca Pacioli (véase la siguiente sección) que los artistas y arquitectos conocieron la proporción áurea.[11]

Una conferencia de 2003 acerca de la arquitectura medieval resultó en el libro Ad Quadratum: The Application of Geometry to Medieval Architecture (Ad Quadratum: La aplicación de geometría a la arquitectura medieval)[20]. De acuerdo a la reseña de un crítico:

Most of the contributors consider that the setting out was done ad quadratum, using the sides of a square and its diagonal. This gave an incommensurate ratio of by striking a circular arc (which could easily be done with a rope rotating around a peg). Most also argued that setting out was done geometrically rather than arithmetically (with a measuring rod). Some considered that setting out also involved the use of equilateral or Pythagorean triangles, pentagons, and octagons. Two authors believe the Golden Section (or at least its approximation) was used, but its use in medieval times is not supported by most architectural historians.La mayoría de los contribuidores consideran que el trazo fue hecho ad quadratum, usando los lados de un cuadrado y su diagonal. Esto le dio una relación inconmensurable de al conectar un arco de círculo (que podría ser hecho fácilmente con una cuerda que gira alrededor de una clavija). La mayoría también argumentan que el trazo fue hecho geométricamente más que aritméticamente (con una vara para medir). Algunos consideran que este trazo también involucró el uso de triángulos, pentágonos y octógonos equiláteros o pitagóricos. Dos autores creen que se usó la Sección Dorada (o al menos su aproximación), pero su uso en tiempos medievales no es apoyado por la mayoría de historiadores arquitectónicos.Architectural Science Review[21]

El historiador arquitectónico australiano John James hizo un estudio detallado de la Catedral de Chartres. En la página 157 de dicho libro sostiene que el maestro constructor del equipo que él denomina "Bronce" usó la proporción áurea. Era la misma relación que había entre los brazos de su cuadro de metal:

Bronze by comparison was an innovator, in practical rather than in philosophic things. Amongst other things Bronze was one of the few masters to use the fascinating ratio of the golden mean. For the builder, the most important function Fi, as we write the golden mean, is that if the uses is consistently he will find that every subdivision, no matter how accidentally it may have been derived, will fit somewhere into the series. Is not too difficult a ratio to reproduce, and Bronze could have had the two arms of his metal square cut to represent it. All he would than have had to do was to place the square on the stone and, using the string draw between the corners, relate any two lengths by Phi. Nothing like making life easy.Bronce, en comparación, era un innovador, en las cosas prácticas más que las filosóficas. Entre otras cosas, Bronce fue uno de los primeros maestros que usaron la fascinante relación de la proporción dorada. Para el constructor, la función más importante Fi, que es como se escribe la medida dorada, es que si se usa de forma consistente se encontrará que cada subdivisión, sin importar qué tan accidentalmente se haya derivado, entrará en algún punto en la serie. No es una proporción difícil de reproducir, y Bronce pudo cortar los dos brazos de su cuadrado de metal para representarlo. Todo lo que debía hacer entonces era colocar el cuadrado en la piedra y, usando una cuerda tensa entre las esquinas, relacionar cualesquiera dos longitudes a través de Fi. Nada como hacerse la vida fácilJohn James, The master masons of Chartres[22]

Arte[editar]

Renacimiento[editar]

De divina proportione, escrito por Luca Pacioli en Milán entre 1946 y 1948, publicado en 1509,[23] contiene 60 ilustraciones hechas por Leonardo da Vinci, algunas de las cuales ilustran la apariencia de la razón dorada en figuras geométricas. A partir de la obra de Leonardo da Vinci, este tratado arquitectónico fue una influencia importante en generaciones de artistas y arquitectos.

Hombre de Vitruvio, creado por Leonardo da Vinci alrededor de 1490[24] está basada en las teorías del hombre del cual toma nombre el dibujo, Vitruvio, quien señaló en De Architectura que la planeación de templos depende de la simetría que a su vez se debe basar en las proporciones perfectas del cuerpo humano. Algunos autores[¿quién?] han señalado que no hay evidencia de que Da Vinci usara la razón áurea en Hombre de Vitruvio;[25] sin embargo Olmos[3] (1991) observa algo diferente a través del análisis geométrico. También propone que su Autorretrato, David, de Miguel Ángel, Melancolía I de Durero, y el diseño clásico del violín de los maestros de Cremona (Guarneri, Stradivari y miembros de la familia Amati) tienen líneas similares a la razón áurea.

La Gioconda (también conocida como Mona Lisa, 1503–1506) "ha sido el centro de discusión de tantos volúmenes de especulaciones académicas y populares que es imposible alcanzar ninguna conclusión sin ambiguedad", dice Livio, hablando acerca de la razón áurea.[11]

La capilla de Tempietto en el monasterio de San Pietro en Montorio, Roma, fue construido por Bramante, tiene relaciones con la proporción áurea en sus líneas de elevación e interiores.[26]

Baroque and Spanish empire[editar]

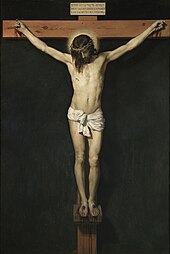

José Villagrán García has claimed[27] that the golden ratio is an important element in the design of the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral (circa 1667–1813). Olmos claims the same for the design of the cities of Coatepec (1579), Chicoaloapa (1579) and Huejutla (1580), as well as the Mérida Cathedral, the Acolman Temple, Cristo Crucificado by Diego Velázquez (1639) and La Madona de Media Luna[28] of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.[3]

Neo-Impressionism[editar]

Matila Ghyka[29] and others[30] contend that Georges Seurat used golden ratio proportions in paintings like La Parade, Le Pont de Courbevoie and Bathers at Asnières. However, there is no direct evidence to support these claims.[31]

While the golden ratio appears to govern the geometric structure of Seurat's Parade de cirque (Circus Sideshow),[32][33] modern consensus among art historians is that Seurat never used this divine proportion in his work.[34][35][36]

The final study of Parade, executed prior to the oil on canvas, is divided horizontally into fourths and vertically into sixths (4 : 6 ratio) corresponding to the dimensions of the canvas, which is one and one-half times wider than its vertical dimension. These axes do not correspond precisely to the golden section, 1 : 1.6, as might have been expected. Rather, they correspond to basic mathematical divisions (simple ratios that appear to approximate the golden section), as noted by Seurat with citations from the mathematician, inventor, esthetician Charles Henry.[34]

Cubism[editar]

The idea of the Section d'Or (or Groupe de Puteaux) originated in the course of conversations between Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger and Jacques Villon. The group's title was suggested by Villon, after reading a 1910 translation of Leonardo da Vinci's Trattato della Pittura by Joséphin Péladan. Peladan attached great mystical significance to the golden section (en francés: Section d'Or), and other similar geometric configurations. For Villon, this symbolized his belief in order and the significance of mathematical proportions, because it reflected patterns and relationships occurring in nature. Jean Metzinger and the Duchamp brothers were passionately interested in mathematics. Jean Metzinger, Juan Gris and possibly Marcel Duchamp at this time were associates of Maurice Princet, an amateur mathematician credited for introducing profound and rational scientific arguments into Cubist discussions.[37] The name La Section d'Or represented simultaneously a continuity with past traditions and current trends in related fields, while leaving open future developments in the arts.[38][39]

Surrealism[editar]

The Sacrament of the Last Supper (1955): The canvas of this surrealist masterpiece by Salvador Dalí is a golden rectangle. A huge dodecahedron, with edges in golden ratio to one another, is suspended above and behind Jesus and dominates the composition.[11][40]

De Stijl[editar]

Some works in the Dutch artistic movement called De Stijl, or neoplasticism, exhibit golden ratio proportions. Piet Mondrian used the golden section extensively in his neoplasticist, geometrical paintings, created circa 1918–38.[30][41] Mondrian sought proportion in his paintings by observation, knowledge and intuition, rather than geometrical or mathematical methods.[42]

Recent architecture[editar]

Mies van der Rohe[editar]

The Farnsworth House, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, has been described as "the proportions, within the glass walls, approach 1:2"[43] and "with a width to length ratio of 1:1.75 (nearly the golden section)"[44] and has been studied with his other works in relation to the golden ratio.[45]

Le Corbusier[editar]

The Swiss architect Le Corbusier, famous for his contributions to the modern international style, centered his design philosophy on systems of harmony and proportion. Le Corbusier's faith in the mathematical order of the universe was closely bound to the golden ratio and the Fibonacci series, which he described as "rhythms apparent to the eye and clear in their relations with one another. And these rhythms are at the very root of human activities. They resound in man by an organic inevitability, the same fine inevitability which causes the tracing out of the Golden Section by children, old men, savages and the learned."[46]

Modulor: Le Corbusier explicitly used the golden ratio in his system for the scale of architectural proportion. He saw this system as a continuation of the long tradition of Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci's "Vitruvian Man", the work of Leon Battista Alberti, and others who used the proportions of the human body to improve the appearance and function of architecture. In addition to the golden ratio, Le Corbusier based the system on human measurements, Fibonacci numbers, and the double unit. He took Leonardo's suggestion of the golden ratio in human proportions to an extreme: he sectioned his model human body's height at the navel with the two sections in golden ratio, then subdivided those sections in golden ratio at the knees and throat; he used these golden ratio proportions in the Modulor system.[47]

In The Modulor: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale, Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics Le Corbusier reveals he used his system in the Marseilles Unite D'Habitation (in the general plan and section, the front elevation, plan and section of the apartment, in the woodwork, the wall, the roof and some prefabricated furniture), a small office in 35 rue de Sèvres, a factory in Saint-Die and the United Nations Headquarters building in New York City.[48] Many authors claim that the shape of the facade of the second is the result of three golden rectangles;[49] however, each of the three rectangles that can actually be appreciated have different heights.

Josep Lluís Sert[editar]

Catalan architect Josep Lluis Sert, a disciple of Le Corbusier, applied the measures of the Modulor in all his particular works, including the Sert's House in Cambridge[cita requerida] and the Joan Miró Foundation in Barcelona.[50]

Neogothic[editar]

According to the official tourism page of Buenos Aires, Argentina, the ground floor of the Palacio Barolo (1923), designed by Italian architect Mario Palanti, is built according to the golden section.[51]

Post-modern[editar]

Another Swiss architect, Mario Botta, bases many of his designs on geometric figures. Several private houses he designed in Switzerland are composed of squares and circles, cubes and cylinders. In a house he designed in Origlio, the golden ratio is the proportion between the central section and the side sections of the house.[52]

Music[editar]

Ernő Lendvai analyzes Béla Bartók's works as being based on two opposing systems, that of the golden ratio and the acoustic scale,[53] though other music scholars reject that analysis.[11] In Bartók's Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta the xylophone progression occurs at the intervals 1:2:3:5:8:5:3:2:1.[54] The French composer Erik Satie used the golden ratio in several of his pieces, including Sonneries de la Rose+Croix.

The golden ratio is also apparent in the organisation of the sections in the music of Claude Debussy's Image: Reflections in the Water, in which "the sequence of keys is marked out by the intervals 34, 21, 13 and 8, and the main climax sits at the phi position."[54]

The musicologist Roy Howat has observed that the formal boundaries of Debussy’s La mer correspond exactly to the golden section.[55] Trezise finds the intrinsic evidence "remarkable", but cautions that no written or reported evidence suggests that Debussy consciously sought such proportions.[56]

Leonid Sabaneyev hypothesizes that the separate time intervals of the musical pieces connected by the "culmination event", as a rule, are in the ratio of the golden section.[57] However the author attributes this incidence to the instinct of the musicians: "All such events are timed by author's instinct to such points of the whole length that they divide temporary durations into separate parts being in the ratio of the golden section."

Ron Knott[58] exposes how the golden ratio is unintentionally present in several pieces of classical music:

- An article of American Scientist[59] (Did Mozart use the Golden mean?, March/April 1996), reports that John Putz found that there was considerable deviation from ratio section division in many of Mozart's sonatas and claimed that any proximity to this number can be explained by constraints of the sonata form itself.

- Derek Haylock[60] claims that the opening motif of Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (c. 1804–08), occurs exactly at the golden mean point 0.618 in bar 372 of 601 and again at bar 228 which is the other golden section point (0.618034 from the end of the piece) but he has to use 601 bars to get these figures. This he does by ignoring the final 20 bars that occur after the final appearance of the motif and also ignoring bar 387.

According to author Leon Harkleroad, "Some of the most misguided attempts to link music and mathematics have involved Fibonacci numbers and the related golden ratio."[61]

Notas[editar]

- ↑ De acuerdo con Boussora y Mazouz:[16]

The geometric technique of construction of the golden section seems to have determined the major decisions of the spatial organisation. The golden section appears repeatedly in some part of the building measurements. It is found in the overall proportion of the plan and in the dimensioning of the prayer space, the court and the minaret. The existence of the golden section in some parts of Kairouan mosque indicates that the elements designed and generated with this principle may have been realised at the same period.La técnica geométrica de construcción de la sección de oro parece haber determinado las decisiones mayores de la organización espacial. La sección dorada aparece repetidamente en parte de las medidas del edificio. Se encuentra en la proporción general del plan y en las dimensiones del espacio de oración, el patio y el minaret. La existencia de la sección dorada en algunas partes de la MEzquita de Kairuán indica que los elementos diseñados y generados con este principio pueden haber sido realizados en el mismo periodo.

Referencias[editar]

- ↑ a b c Markowsky, George (1992). «Misconceptions about the Golden Ratio». The College Mathematics Journal (JSTOR) 23 (1): 2. doi:10.2307/2686193. Consultado el 23 de abril de 2017.

- ↑ a b c d Klaus, Mainzer (1996). Symmetries of Nature: A Handbook for Philosophy of Nature and Science [Simetrías de la naturaleza: Un manual de Filosofía de la Naturaleza y Ciencia]. Walter de Gruyter. p. 118. ISBN 3-11-012990-6.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Chanfón Olmos, Carlos. Curso sobre Proporción. Procedimientos reguladores en construcción. Convenio de intercambio UNAM–UADY. México - Mérida, 1991

- ↑ Trivede, Prash. The 27 Celestial Portals: The Real Secret Behind the 12 Star-Signs. Lotus Press. p. 397.

- ↑ Elam, Kimberly. Geometry of Design: Studies in Proportion and Composition By Kimberly Elam. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 6.

- ↑ Lidwell, William; Holden, Kritina; Butler, Jill (1 de octubre de 2003). Universal Principles of Design. Rockport Publishers. p. 96.

- ↑ Pile, John F (2005). A history of interior design. Laurence King Publishing. p. 29.

- ↑ Maor, Eli (2000). Trigonometric Delights. Princeton Univ. Press.

- ↑ Bell, Eric Temple (1940). The Development of Mathematics. New York: Dover. p. 40.

- ↑ a b van Mersbergen, Audrey M. (1998). «Rhetorical prototypes in architecture: Measuring the acropolis with a philosophical polemic». Communication Quarterly (Informa UK Limited) 46 (2): 194-213. doi:10.1080/01463379809370095. Consultado el 23 de abril de 2017.

- ↑ a b c d e Livio, Mario (2002). The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, The World's Most Astonishing Number. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0815-5.

- ↑ Hemenway, Priya (2005). Divine Proportion: Phi In Art, Nature, and Science [Proporción divina: Fi en el Arte, Naturaleza y Ciencia]. New York: Sterling. p. 96. ISBN 1-4027-3522-7.

- ↑ Cook, Theodore Andrea, Sir (1914). The curves of life; being an account of spiral formations and their application to growth in nature, to science and to art; with special reference to the manuscripts of Leonardo da Vinci (en inglés estadounidense). Constable and Company. p. 420. Consultado el 22 de abril de 2017. «Mr. Mark Barr suggested to Mr. Schooling that this ratio should be called the φ proportion for reasons given below».

- ↑ Amabilis, Manuel (1956). La arquitectura precolombina en México. México: Orion. pp. 200, 202. OCLC 163693814.

- ↑ Pile, John F. (2005). A History of Interior Design (en inglés estadounidense). Laurence King Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 9781856694186. Consultado el 23 de abril de 2017.

- ↑ Boussora, Kenza; Mazouz, Said (Primavera 2004). «The Use of the Golden Section in the Great Mosque of Kairouan» [El Uso de la Sección Áurea en la Gran Mezquita de Kairuán]. Nexus Network Journal 6 (1): 7-16. doi:10.1007/s00004-004-0002-y.

- ↑ Brinkworth, Peter; Scott, Paul (2001). «The Place of Mathematics». Australian Mathematics Teacher 57 (3): 2.

- ↑ Pile, John F. (2005). A history of interior design. Laurence King Publishing. p. 88.

- ↑ Montserrat, Lloveras (11 de marzo de 2008). «La Lumière à Sénanque». Pàgina inicial de UPCommons. ISSN 0774-4919. Consultado el 3 de mayo de 2017.

- ↑ Wu, Nancy (2002). Ad quadratum : the practical application of geometry in medieval architecture. Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-1960-4.

- ↑ «The geometry of Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals. (Ad Quadratum: The Application of Geometry to Medieval Architecture) (Book Review)». Architectural Science Review 46 (3): 337-338. September 1, 2003.

- ↑ James, John (1990). The master masons of Chartres. Sydney New York Wolfboro, N.H., U.S.A: West Grinstead Pub. Boydell & Brewer distributor. ISBN 0-646-00805-6.

- ↑ a b Pacioli, Luca (1509). Divina proportione : opera a tutti glingegni perspicaci e curiosi necessaria oue ciascun studioso di philosophia: prospettiua pictura sculptura: architectura: musica: e altre mathematice: suavissima: sotile: e admirabile doctrina consequira: e delecterassi: co[n] varie questione de secretissima scientia. Consultado el 11 de mayo de 2017.

- ↑ Joseph., Turbeville, (2000). A glimmer of light from the eye of a giant : tabular evidence of a monument in harmony with the universe. Trafford. ISBN 9781552124017. OCLC 44265298.

- ↑ Keith Devlin (Junio 2004). «Good stories, pity they're not true». www.maa.org (en inglés estadounidense). Consultado el 24 de julio de 2017.

- ↑ Pile, John F. A history of interior design . Laurence King Publishing. 2005. Page 130.

- ↑ Villagran Garcia, Jose. Los Trazos Reguladores de la Proporcion Arquitectonica. Memoria de el Colegio Nacional, Volume VI, No. 4, Editorial de El Colegio Nacional, Mexico, 1969

- ↑ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Inmaculada_Concepci%C3%B3n_(Murillo,_1665).jpg

- ↑ Ghyka, Matila. The Geometry of Art and Life. 1946. Page 162

- ↑ a b Staszkow, Ronald and Bradshaw, Robert. The Mathematical Palette. Thomson Brooks/Cole. P. 372

- ↑ Keith Devlin (June 2004). «Good stories, pity they're not true». MAA Online. Mathematical Association of America. Archivado desde el original el 1 de julio de 2013.

- ↑ Michael F. Zimmermann. Seurat and the Art Theory of His Time. Antwerp, 1991

- ↑ André Lhote, Encyclopédie française. Vol. 16, part 1, Arts et littératures dans la société contemporaine. Paris, 1935, p. 16.30-7, ill. pp. 16.30-6, 16.31-7

- ↑ a b Robert L. Herbert, Georges Seurat, 1859-1891, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991, pp. 340-345, archive.org (full text online)

- ↑ Roger Herz-Fischler. An Examination of Claims Concerning Seurat and The Golden Number. Gazette des beaux-arts, 6th ser., 101 (March 1983), pp. 109–12 n. 12

- ↑ Marguerite Neveux. Construction et proportion: apports germaniques dans une theorie de la peinture franchise de 1850 a 1950. Université de Paris (Ph.D. diss.), 1990

- ↑ The History and Chronology of Cubism, p. 5

- ↑ La Section d'Or, Numéro spécial, 9 Octobre 1912

- ↑ Balmori, Santos, Aurea mesura, Unam, 1978, 189 p. P. 23-24.

- ↑ Hunt, Carla Herndon and Gilkey, Susan Nicodemus. Teaching Mathematics in the Block pp. 44, 47, ISBN 1-883001-51-X

- ↑ Bouleau, Charles, The Painter's Secret Geometry: A Study of Composition in Art (1963) pp. 247-48, Harcourt, Brace & World, ISBN 0-87817-259-9

- ↑ Padovan, Richard. Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture. Taylor & Francis. Page 26.

- ↑ Neil Jackson (1996). The Modern Steel House. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-419-21720-7.

- ↑ Leland M. Roth (2001). American Architecture: A History. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3661-9.

- ↑ Sano, Junichi. Study on the Golden Ratio in the works of Mies van der Rolle : On the Golden Ratio in the plans of House with three Courts and IIT Chapel. Journal of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Engineering (Academic Journal, 1993 ) 453,153-158 / ,

- ↑ Le Corbusier, The Modulor p. 25, as cited in Padovan, Richard, Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture (1999), p. 316, Taylor and Francis, ISBN 0-419-22780-6

- ↑ Le Corbusier, The Modulor, p. 35, as cited in Padovan, Richard, Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture (1999), p. 320. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-419-22780-6: "Both the paintings and the architectural designs make use of the golden section".

- ↑ Le Corbusier, The Modulor: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale, Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics, Birkhäuser, 2000, p. 130

- ↑ Daniel Pedoe (1983). Geometry and the Visual Arts. Courier Dover Publications. p. 121. ISBN 0-486-24458-X.

- ↑ es:Fundación Joan Miró

- ↑ Official tourism page of the city of Buenos Aires

- ↑ Urwin, Simon. Analysing Architecture (2003) pp. 154-5, ISBN 0-415-30685-X

- ↑ Lendvai, Ernő (1971). Béla Bartók: An Analysis of His Music. London: Kahn and Averill.

- ↑ a b Smith, Peter F. The Dynamics of Delight: Architecture and Aesthetics (New York: Routledge, 2003) pp 83, ISBN 0-415-30010-X

- ↑ Roy Howat (1983). Debussy in Proportion: A Musical Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31145-4.

- ↑ Simon Trezise (1994). Debussy: La Mer. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-521-44656-2.

- ↑ Sabaneev, Leonid and JOFFE, Judah A. Modern Russian Composers. 1927.

- ↑ Knott, Ron, [Ron Knott's web pages on Mathematics], Fibonacci Numbers and The Golden Section in Art, Architecture and Music, Surrey University

- ↑ May, Mike, Did Mozart use the Golden mean?, American Scientist, March/April 1996

- ↑ Haylock, Derek. Mathematics Teaching, Volume 84, p. 56-57. 1978

- ↑ Leon Harkleroad (2006). The Math Behind the Music. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81095-7.

External links[editar]

- Nexux Network Journal – Architecture and Mathematics Online. Kim Williams Books