Usuario:Spirit-Black-Wikipedista/Tíbet durante la Dinastía Ming

La naturaleza exacta de las relaciones sino-tibetanas durante la Dinastía Ming (1368–1644) en China no está clara. Algunos estudiosos modernos que viven y trabajan en la República Popular de China, como Wang Jiawei y Nyima Gyaincain, afirman que la Dinastía Ming ostentaba de una soberanía absoluta sobre el Tíbet, señalando la emisión por parte de la corte Ming de varios títulos los líderes tibetanos, a la plena aceptación de dichos títulos por parte de los tibetanos, además de un proceso de renovación de estos mismos títulos para los sucesores que implicaba viajar a la capital Ming. Los estudiosos dentro de la RPC argumentan, asimismo, que el Tíbet ha formado parte integral de la China desde el siglo XIII, por lo tanto, formando una parte del Imperio Ming. Sin embargo, la mayoría de los estudiosos fuera de la RPC, como Turrell V. Wylie, Melvin C. Goldstein, y Helmut Hoffman, afirman que la relación era de soberanía, que los títulos Ming eran solamente nominales, que el Tíbet seguía siendo una región independiente fuera del control Ming, y que simplemente pagaban los tributos hasta el reinado de Jiajing (1521–1566), quien suspendió las relaciones con el Tíbet.

Algunos estudiosos señalan que durante el período Ming los líderes tibetano se veían involucrados en guerras civiles y llevaban a cabo sus esfuerzos diplomáticos con estados vecinos como Nepal. Algunos estudiosos subrayan la importancia del aspecto comercial de la relación Ming-Tíbet, afirmando que la Dinastía Ming padecía de una escasez de caballos de guerra, y de ahí la importancia del comercio del caballo con Tíbet. Otros argumentan que los estudios modernos subestiman la importancia de la naturaleza religiosa de la relación de la corte Ming con los lamas tibetanos. Con la esperanza de reavivar la relación única existente entre el antiguo líder mongol, el Kublai Khan (1260-1294) y su superior espiritual, Drogön Chögyal Phagpa (1235-1280) de la secta tibetana de Sakya, el Emperador Yongle de los Ming (1402-1424) hizo hincapié en construir una alianza secular y religiosa con Deshin Shekpa (1384-1415), el Karmapa de la secta de los Sombreros Negros tibetanos. Sin embargo, los intentos de Yongle en este sentido no tuvieron éxito.

Los Ming iniciaron una intervención armada de forma esporádica en el Tíbet durante el siglo XIV, pero no sitiaron tropas permanentes ahí. A veces, los tibetanos usaron además la resistencia armada contra los extranjeros Ming. El emperador Wanli (r. 1572–1620) intentó restablecer las relaciones sino-tibetanas tras la alianza Mongol-Tibetana iniciada en 1578, un aspecto que terminó afectando la política diplomática de la subsecuente Dinastía Qing (1644–1912) de China, en su apoyo al Dalái Lama de la secta Yellow Hat. Hacia finales del siglo XVI, los mongoles ya eran protectores armados exitosos del Dalái Lama de la secta Yellow Hat, tras incrementar su presencia en la región Amdo. Esto culminó en la conquista de Gushi Khan del Tíbet de 1637 a 1642.

Contexto[editar]

Imperio mongol[editar]

El Tibet logró ser un fuerte poder contemporáneo junto a la Dinastía Tang (618–907). El Imperio Tibetano fue el mayor rival de los Tang en el control de Asia hasta su caída en el siglo IX.[3][4] Los gobernantes Yarlung del Tíbet firmaron múltiples tratados de paz con los Tang, culminando en un tratado en 821 que fijaba las fronteras entre el Tíbet y China.[5] Durante el período de las Cinco Dinastías y los Diez Reinos (907–960) en China, tras el cual el desquebrajado reino de China no vio amenaza en el Tíbet que se convirtió en una zona de inestabilidad política, hubo una pequeña oportunidad para las relaciones Sino-Tibetanas.[6][7] Actualmente, sobreviven pocos documentos que impliquen la temáticas de las relaciones Sino-Tibetanas de la Dinastía Song (960–1279).[7][8] Los Song estuvieron mucho mas preocupados con la lucha contra los estados enemigos del norte de la Dinastía Liao gobernada por Kitán (907–1125) y la Dinastía Jin gobernada por la Yurchen (1115–1234).[8]

En 1207, el soberano mongol Genghis Khan (r. 1206–1227) conquistó y subyugó al Imperio tangut (1038–1227) —en Xia Occidental.[9] Ese mismo año, estableció relaciones diplomáticas con el Tibet a través del envío de emisarios a dicho lugar.[10] a conquista del estado tangut alarmó a los gobernantes tibetanos, que a raíz de ello decidieron rendirle tributo a los mongoles.[9] Sin embargo, una vez que cesaron el pago del tributo tras la muerte de Genghis Khan, su sucesor Ogedei Khan (r. 1229–1241) ordenó una invasión a la región del Tíbet.[11] Incluso, el príncipe mongol Godan Khan, nieto de Genghis Khan, logró irrumpir en Lhasa, capital del Tíbet.[9][12] Durante su ataque en 1240, este último convocó a Sakya Pandita (1182–1251), líder de la secta budista-tibetana Sakya, a su corte radicada en lo que ahora es la provincia de Gansu, en la región oriental de China.[9][12] Tras la sumisión de Sakya Pandita a Godan en 1247, el Tíbet se incorporó de forma oficial al Imperio mongol durante el régimen de Toregene Khatun (1241–1246).[12][13] Michael C. van Walt van Praag refirió que Godan le garantizó en su momento a Sakya Pandita la autoridad temporal sobre un Tíbet aún fragmentado políticamente, diciéndole que «esta investidura ocasionaría en realidad un impacto menor», sin embargo ésta fue significativa en la medida de que fue la causante del establecimiento de la única relación «sacerdote-patrón» entre los mongoles y los lamas sakya tibetanos.[9]

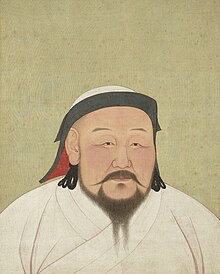

Desde 1236, se le concedió al príncipe mongol Kublai (1260–1294) una gran herencia en la región norte de China por su superior Ogedei Khan.[14] Karma Pakshi (1203–1283) —líder de los lama y segundo Karmapa de la secta tibetana Black Hat— rechazó la invitación de Kublai para aparecer en su juzgado, así que en cambio Kublai invitó a Drogon Chogyal Phagpa (1235–1280), sucesor y sobrino de Sakya Pandita, a ir a su corte en 1253.[15][16][17] Kublai instituyó una relación única con los lama Phagpa, que lo reconocieron como un soberano superior en cuestiones políticas, mientras que los lama Phagpa serían los instructores superiores de Kublai en temáticas de tipo religioso.[15][17][18] Kublai convirtió asimismo al Drogon Chogyal Phagpa en el rey y sacerdote del Tíbet, llegando así a gobernar hasta trece estados diferentes gobernados por miriarquías.[17][18][19]

Kublai Khan no conquistó la Dinastía Song al sur de China sino hasta 1279, así que el Tíbet era un componente más del primerizo Imperio mongol, antes de que se combinara con uno de sus imperios descendientes conocido como la Dinastía Yuan (1271–1368), junto al resto de China.[17]Van Praag concluyó que esta conquista había «marcado el fin de la China independiente», la cual se incorporó entonces en la Dinastía Yuan que gobernó a China, Tíbet, Mongolia y algunas partes de Corea, Siberia y Burma superior.[20] Morris Rossabi escribió que «Khubilai deseaba serpercibido tanto como el Khan de los Khanes de los Mongoles y como Emperador de China. Aunque el se había, por principios de la década de 1260, identificado estrechamente con China, todavía, durante un tiempo, afirmó un gobierno universal», y sin embargo «a pesar de sus éxitos en China y Corea, Kublai no pudo haberse aceptado como el Gran Khan».[21] Por ende, con una aceptación limitada de su posición como Gran Khan, a Kublai Khan se le indentificó cada vez más con China y buscó el apoyo para que fuese nombrado emperador de ésta.[22]

Derrocamiento de Sakya y Yuan[editar]

En 1358, el régimen virreinal Sakya instalado por los mongoles en el Tíbet fue derrocado en una rebelión iniciada por el miriarca Phagmodrupa Janchub Gyaltsän (Byang chub rgyal mtshan, 1302–1364).[20][23][24] La corte mongol Yuan se vio obligada a aceptarlos como los nuevos virreyes, y Janchub Gyaltsän y sus sucesores, la Dinastía Phagmodrupa, ganaron de facto hegemonía sobre el Tíbet.[20][23][24] En 1368, una revuelta encabezada por la etnia han en China, conocida como la Rebelión roja del turbante, derrocó a la Dinastía Yuan en China. Zhū Yuánzhāng estableció la Dinastía Ming, proclamándose emperador en el Yintian bajo el nombre de Hongwu (r. 1368–1398).[25]

No se sabe hasta qué punto la corte de los Ming estaba al corriente de las guerras civiles entre los lineajes budistas tibetanos, pero los emperadores querían evitar que este país se convirtiera en una amenaza como bajo los Tang, y deseaban mantener contactos con tibetanos influyentes.[23][26] Hongwu sin embargo no reconoce oficialmente el poder de los Phagmodru, y se acerca más bien al karmapa cuyo lineaje está bien implantado en el Kham y en el sureste del Tibet, unas regiones más próximas a China, enviando delegados al Tibet durante los inviernos de 1372–1373 para pedir que los titulares de las funciones atribuidas por los mongoles renueven su título y su obediencia.[23] Como es evidente en sus edictos imperiales, Hongwu era muy consciente del vínculo entre el Tíbet budista y China, razón por la cual, quería fomentar la relación.[27][28] No obstante, Rolpe Dorje (1340–1383), cuarto karmapa, rechaza su invitación a la corte de Nanjing y sólo envía a algunos discípulos.[23] Aunque los edictos de Hongwu manifiesten su preocupación por mantener lazos budistas con el Tibet y que envíe una misión en 1378–1382 en busca de textos budistas (liderada por su consejero religioso, el monje Zongluo) al contrario de los soberanos mongoles, no favorece el budismo tibetano. [27][28] De hecho, al principio de la dinastía, está prohibido convertirse a esa forma de religión durante algún tiempo;[29] se conocen pocos monjes chinos, y aún menos laícos, que practiquen el budismo tántrico antes de la época republicana (1912–1949).[29] Según Morris Rossabi, «hubo que esperar al reino de Yongle (r. 1402–1424) para asistir a un intento real de desarrollar las relaciones sino-tibetanas».[30]

Las afirmaciones en el Mingshi[editar]

De acuerdo al trabajo sobre la historia de la Dinastía Ming (二十四史), la Historia de Ming (o Mingshi en chino), recopilada en 1739 por la Dinastía Qing (1644–1912), la Dinastía Ming estabeció la "Oficina Mariscal del Ejército Civil E-Li-Si" (Chino: 俄力思軍民元帥府) en el occidente del Tíbet e instaló la "Comandancia Itinerante Superior Dbus-Gtsang" (Chino: 烏思藏都指揮使司) y asimismo la "Comandancia Itinerante Superior Mdo-khams" (Chino: 朵甘衛都指揮使司) para administrar el este del Tíbet.[31][32] Los Mingshi consignaban qué oficinas administrativas se establecerían como comandancias superiores, incluyendo a una Comandancia Itinerante (Chino: 指揮使司), tres Comisionados de Pacificación de las Oficinas (Chino: 宣尉使司), seis Comisionados de la Oficina de Expedición (Chino: 招討司), cuatro oficinas Wanhu (Chino: 萬戶府, cada miriarca al mando de 10.000 hogares), y diecisiete oficinas Qianhu (Chino: 千戶所, cada quiliarca al mando de 1.000 hogares).[33]

La corte Ming nombraba a tres Príncipes del Dharma (法王) y cinco Príncipes (王), y otorgaba muchos otros títulos, como el Gran Tutor Estatal (大國師) y Tutor Estatal (國師), a los más importantes académicos del budismo tibetano, incluyendo a la sectas Karma Kagyu, Sakya, y Gelug.[34] De acuerdo a Wang Jiawei y Nyima Gyaincain, los académicos líderes de estos organismos fueron nombrados por el gobierno central y estaban sujetos a las leyes del gobierno.[35] Yet Van Praag describe el código de ley tibetano establecido por el gobernador Phagmodru Janchub Gyaltsän como una de las muchas reformas para revivir las viejas tradiciones imperiales tibetanas.[36]

El difunto Turrell V. Wylie, profesor de la Universidad de Washington, y Li Tieh-tseng argumentaron que la exactitud de la censurada Mingshi como una fuente creíble en las relaciones Sino-Tibetanas es cuestionable, en la luz de la erudición moderna.[37] Otros historiadores también afirmaron que estos títulos Ming fueron nominales y en realidad no confieren la autoridad que los títulos Yuan conferían.[38][39] Van Praag escribe que «numerous economically motivated Tibetan missions to the Ming Court are referred to as 'tributary missions' in the Ming Shih».[40] Van Praag expresa que estas «misiones tributarias» se pidieron simplemente por la necesidad de China de caballos procedentes del Tíbet, desde que un mercado de caballos viable en tierras mongolas fue cerrado debido a los conflictos incesantes.[40]

Debates académicos modernos[editar]

Herencia, nuevos nombramientos y títulos[editar]

Transición de Yuan a Ming[editar]

Los historiadores discrepan sobre cuál fue la relación entre la corte Ming y el Tíbet y si la China Ming otorgó o no soberanía sobre éste. Van Praag escribe que los historiadores de la corte china vieron al Tíbet como un lugar independiente y tributario y tenían poco interés en el Tíbet además de una relación patrón-lama.[41][42] El historiador Tsepon Wangchuk Deden Shakabpa (Xagabba Wangqug Dedain) apoya la posición de Van Praag.[41] Sin embargo, Wang Jiawei y Nyima Gyaincain argumentan que estas afirmaciones por Van Praag y Xagabba son «falacias».[41]

Wang y Nyima argumentan que el emperador Ming envió edictos al Tíbet dos veces en el segundo año de la Dinastía Ming, y demostró que veía al Tíbet como una región pacífica para que diversas tribus tibetanas se sometiesen a la autoridad de la corte Ming.[41] Señalan que, al mismo tiempo, el príncipe mongol Punala, que había heredado su posición como gobernante de las zonas del Tíbet, fue a Nanjing en 1371 para rendir homenaje y mostrar su lealtad a la corte Ming, trayendo consigo el sello de la autoridad emitida por la corte Yuan.[43] Asimismo afirman que, puesto que los sucesores de los lamas le otorgaron el título de «príncipe» tuvo que viajar a la corte Ming para renovarlo, y desde que los lamas se proclamaron ellos mismos «príncipes», la corte Ming tuvo «plena soberanía sobre el Tíbet».[44] Argumentaron que la Dinastía Ming, mediante la emisión de edictos imperiales para invitar a antiguos funcionarios de Yuan a la corte con tal de ocupar posiciones oficiales en los primeros años de su fundación, ganó submisión de parte de los antiguos líderes religiosos y administrativos Yuan en las áreas tibetanas, e incorporaron estas áreas a la autoridad de la corte Ming. Por lo tanto, concluyen, que la corte Ming ganó el poder de gobernar las áreas tibetanas que antes estaban bajo el control de la Dinastía Yuan.[44]

En su libro The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama, el autor y periodista Thomas Laird escribe que Wang y Nyima representan el punto de vista del gobierno de la República Popular de China en su Historical Status of China's Tibet, y no se dan cuenta que China fue "absorbida en una unidad politica mayor no China" durante la Dinastía mongol Yuan, la cual Wang y Nyima retratan como una dinastía china típica sucedida por los Ming.[45] Laird afirma que los gobernantes khan de Mongolia nunca administraron Tibet como una parte de China sino como territorios separados, explicando que los mongoles fueron como los británicos que colonizaron a la India y a Nueva Zelanda, señalando que dichas colonizaciones no suponga que India formase parte de Nueva Zelanda.[46] Respecto a posteriores versiones de los mongoles y tibetanos que se refieren a la conquista mongola del Tíbet, Laird afirma que "ellos, al igual que todas las demás versiones que no sean chinas, nunca reflejan la subyugación del Tíbet como una realizada por los chinos."[46]

La Enciclopedia Columbia hace un distinción entre la Dinastía Yuan y los otros khanates del Imperio mongol: Ilkhanate, Chagatai Khanate y el Golden Horde. Decribe la Dinastía Yuan como "Una dinastía mongola de China que gobernó de 1271 a 1368, y una división del gran imperio conquistado por los mongoles. Fundado por el Kublai Khan, que adoptó el nombre dinástico chino de Yüan en 1271."[48] La Encyclopedia Americana describe a la Dinastía Yuan Dynasty como "el lineaje de gobernantes mongoles en China" y que los mongoles "proclamaron a la dinastía tipo-china Yüan en Khanbaliq (Beijing)."[49] El Metropolitan Museum of Art señala que los gobernantes mongoles de la Dinastía Yuan "adoptaron modelos políticos y cultarales chinos; gobernando desde sus capitales en Dadu, asumieron el papel de los emperadores chinos,"[50] aunque el Tibetólogo Thomas Laird rechaza la idea de la Dinastía Yuan como una as a non-Chinese polity y resta importancia a sus características chinas. El Metropolitan Museum of Art también señala que, a pesar de la asimilación paulatina de los monarcas Yuan, los gobernantes Mongol imponían políticas duras y discriminatorias contra los literati y los chinos del sur.[50] Morris Rossabi, profesor de historia asiática en el Queens College, City University of New York, describe ien su obra Kublai Khan: His Life and Times que Kublai "creó institcuciones gubernamentales que, o bien parecían o bien eran iguales que, las tradicionalmente chinas", y que quiso "darles a entender a los chinos que pretendía adoptar las cermonias y estilo propio de un gobernante chino".[51] No obstante, la jerarquía etno-geográfica de las castas Caste#Castas en China favorecían a los mongoles y a otras etnías sobre la mayoría china Han Chinese. Aunque los Han que habían sido reclutados como asesores a menudo gozaban de mayor poder de influencia real que sus superiores, su estatus no estaba bien definido. Kublai también aboló las pruebas imperiales legado de la función pública china, y que no fueron reestablecidas hasta el reinado de Emperor Renzong (1311–1320).[52]. Según Rossabi, Kublai reconoció que para poder gobernar China "aunque tenía que emplear asesores y funcionarios, no podía depender exclusivamente en los asesores chinos porque tenía que mantener un equilibrio delicado entre gobernar sobre la civilización sedentaria de China y de preservar la identidad cultural y valores de los mongoles."[21] Asimismo "a la hora de gobernar sobre China, y aunque se interesó por sus súbditos chinos, también tenía que explotar los recursos del imperio para su propio grandeza. His motivations and objectives alternated from one to the other throughout his reign," according to Rossabi.[53] Van Praag writes in The Status of Tibet that the Tibetans and Mongols, on the other hand, upheld a dual system of rule and an interdependent relationship that legitimated the succession of Mongol khans as universal Buddhist rulers, or chakravartin.[17] Van Praag writes that "Tibet remained a unique part of the Empire and was never fully integrated into it," citing examples such as a licensed border market that existed between China and Tibet during the Yuan.[17]

Ming practices of giving titles to Tibetans[editar]

According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China, the Ming implemented a policy of managing Tibet according to conventions and customs, granting titles and setting up administrative organs over Tibet.[54] The Information Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China states that the Ming Dynasty's Ü-Tsang Commanding Office governed most areas of Tibet.[1] It also states that while the Ming abolished the policy council set up by the Mongol Yuan to manage local affairs in Tibet and the Mongol system of Imperial Tutors to govern religious affairs, the Ming adopted a policy of bestowing titles upon religious leaders who had submitted to the Ming Dynasty.[1] For example, an edict of the Hongwu Emperor in 1373 appointed the Tibetan leader Choskunskyabs as the General of the mNgav-ris Military and Civil Wanhu Office, stating:[55]

I, the sovereign of the Empire, courteously treat people from all corners of the Empire who love righteousness and pledge allegiance to the Court and assign them official posts. I have learned with great pleasure that you, Chos-kun-skyabs, who live in the Western Region, inspired by my power and reputation, are loyal to the Court and capable of safeguarding the territory in your charge. The mNgav-ris Military and Civil Wanhu Office has just been established. I, therefore, appoint you head of the office with the title of General Huaiyuan, believing that you are most qualified for the post. I expect you to be even more conscientious in your work than in the past, to comply with discipline and to care for your men so that security and peace in your region can be guaranteed.[55]

Chen Qingying, Professor of History and Director of the History Studies Institute under the China Tibetology Research Center in Beijing, writes that the Ming court conferred new official positions on ex-Yuan Tibetan leaders of the Phachu Kargyu and granted them lower-ranking positions.[56] Of the county (zong or dzong) leaders of Neiwo Zong and Renbam Zong, Chen states that when "the Emperor learned the actual situation of the Phachu Kargyu, the Ming court then appointed the main Zong leaders to be senior officers of the Senior Command of Dbus and Gtsang."[56] The official posts that the Ming court established in Tibet, such as senior and junior commanders, offices of Qianhu (in charge of 1,000 households), and offices of Wanhu (in charge of 10,000 households), were all hereditary positions according to Chen, but he asserts that "the succession of some important posts still had to be approved by the emperor," while old imperial mandates had to be returned to the Ming court for renewal.[56]

According to Tibetologist John Powers, Tibetan sources counter this narrative of titles granted by the Chinese to Tibetans, with various titles which the Tibetans gave to the Chinese emperors and their officials. Tribute missions from Tibetan monasteries to the Chinese court brought back not only titles, but large, commercially valuable gifts which could subsequently be sold. The Ming emperors sent invitations to ruling lamas, but the lamas sent subordinates rather than coming themselves, and no Tibetan ruler ever explicitly accepted the role of being a vassal of the Ming.[57] Also, Hans Bielenstein writes that as far back as the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), the Han Chinese government "maintained the fiction" that the foreign officials administering the various "Dependent States" and oasis city-states of the Western Regions (composed of the Tarim Basin and oasis of Turpan) were true Han representatives due to the Han government's conferral of Chinese seals and seal cords to them.[58]

Janchub Gyaltsän[editar]

Wang and Nyima state that after the official title "Education Minister" was granted to Janchub Gyaltsän (Byang chub rgyal mtshan, 1302–1364) by the Yuan court, this title appeared frequently with his name in various Tibetan texts, while his Tibetan title "Degsi" is seldom mentioned.[59] Wang and Nyima take this to mean that "even in the later period of the Yuan Dynasty, the Yuan imperial court and the Pagmo Drupa regime maintained a Central-local government relation."[59] Janchub Gyaltsän is even supposed to have written in his will: "In the past I received loving care from the emperor in the east. If the emperor continues to care for us, please follow his edicts and the imperial envoy should be well received."[59]

However, Lok-Ham Chan, a professor of history at the University of Washington, writes that Janchub Gyaltsän's aims were to recreate the old Tibetan Kingdom that existed during the Chinese Tang Dynasty, to build "nationalist sentiment" amongst Tibetans, and to "remove all traces of Mongol suzerainty."[23] Georges Dreyfus, a professor of religion at Williams College, writes that it was Janchub Gyaltsän who adopted the old administrative system of Songtsän Gampo (c. 605–649)—the first Yarlung king to establish Tibet as a strong power—by reinstating its legal code of punishments and administrative units.[60] For example, instead of the 13 governorships established by the Mongol Sakya viceroy, Janchub Gyaltsän divided Central Tibet into districts (dzong) with district heads (dzong dpon) who had to conform to old rituals and wear clothing styles of old Imperial Tibet.[60] Van Praag asserts that Janchub Gyaltsän's ambitions were to "restore to Tibet the glories of its Imperial Age" by reinstating secular administration, promoting "national culture and traditions," and installing a law code that survived into the 20th century.[36]

According to Chen, the Ming officer of Hezhou (modern day Linxia) informed the Hongwu Emperor that the general situation in Dbus and Gtsang "was under control," and so he suggested to the emperor that he offer the second Phagmodru ruler Shakya Gyaltsen (wylie: sh'akya rgyal mtshan, ZYPY: Sagya Gyaincain) an official title.[61] According to the Records of the Founding Emperor, Hongwu issued an edict granting the title "Initiation State Master" to Sagya Gyaincain, while the latter sent envoys to the Ming court to hand over his jade seal of authority along with tribute of colored silk and satin, statues of the Buddha, Buddhist scriptures, and sarira.[61]

Dreyfus writes that after the Phagmodru myriarchy lost its centralizing power over Tibet in 1434, several attempts by other families to establish hegemonies failed over the next two centuries until 1642 with Lozang Gyatso, the Fifth Dalai Lama's effective hegemony over Tibet.[60]

Je Tsongkhapa[editar]

The Ming Dynasty granted titles to sects such as the Black Hat Karmapa lamas, but the latter had previously declined Mongol invitations to receive titles.[62] When the Ming Yongle Emperor invited Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), founder of the Yellow Hat sect, to come to the Ming court and pay tribute, the latter declined.[62] Wang and Nyima write that this was due to old age and physical weakness, and also because of efforts being made to build three major monasteries.[63] Chen Qingying states that Tsongkhapa wrote a letter to decline the Emperor's invitation, and in this reply, Tsongkhapa wrote:[64]

It is not that I don't know it is the edict of the Great dominator of the world for the sake of Buddhist doctrine, or that I do not obey the edict of Your Majesty. I am seriously ill whenever I meet the public, so I cannot embark on a journey in compliance with the imperial edict. I wish that Your Majesty might be merciful, and not be displeased; it will really be a great mercy.[64]

Tom Grunfeld says that Tsongkhapa claimed ill health in his refusal to appear at the Ming court,[65] while Rossabi adds that Tsongkhapa cited the "length and arduousness of the journey" to China as another reason not to make an appearance.[66] This first request by the Ming was made in 1407, but the Ming court sent another embassy in 1413, this one led by the eunuch Hou Xian (候顯; fl. 1403–1427), which was again refused by Tsongkhapa.[66] Rossabi writes that Tsongkhapa did not want to entirely alienate the Ming court, so he sent his disciple Chosrje Shākya Yeshes (Jamchen Choje, 釋迦也失) to Nanjing in 1414 on his behalf, and upon his arrival in 1415 the Yongle Emperor bestowed upon him the title of "State Teacher"—the same title earlier awarded the Phagmodru ruler of Tibet.[62][65][66] The Xuande Emperor (r. 1425–1435) even granted this disciple Chosrje Shākya Yeshes the title of a "King" (王).[62] This title does not appear to have held any practical meaning, or to have given its holder any power, at Tsongkhapa's Ganden monastery. Wylie notes that this—like the Black Hat sect—cannot be seen as a reappointment of Mongol Yuan offices, since the Yellow Hat sect was created after the fall of the Yuan Dynasty.[62]

Implications on the question of rule[editar]

Dawa Norbu, a leading author of the Tibetan diaspora, argues that modern Chinese Communist historians tend to be in favor of the view that the Ming simply reappointed old Yuan Dynasty officials in Tibet and perpetuated their rule of Tibet in this manner.[67] Norbu writes that, although this would have been true for the eastern Tibetan regions of Amdo and Kham's "tribute-cum-trade" relations with the Ming, it was untrue if applied to the western Tibetan regions of Ü-Tsang and Ngari. After the Phagmodru myriarch Janchub Gyaltsän, these were ruled by "three successive nationalistic regimes," which Norbu writes "Communist historians prefer to ignore."[67] Laird writes that the Ming appointed titles to eastern Tibetan princes, and that "these alliances with eastern Tibetan principalities are the evidence China now produces for its assertion that the Ming ruled Tibet," despite the fact that the Ming did not send an army to replace the Mongols after they left Tibet.[68] Yiu Yung-chin states that the furthest western extent of the Ming Dynasty's territory was Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan, while "the Ming did not possess Tibet."[69] Shih-Shan Henry Tsai, a professor of History and Director of Asian Studies at the University of Arkansas, writes that the Yongle Emperor sent his eunuch Yang Sanbao into Tibet in 1413 to gain the allegiance of various Tibetan princes, while Yongle paid a small fortune in return gifts for tributes in order to maintain the loyalty of neighboring vassal states such as Nepal and Tibet.[70] However, Van Praag states that Tibetan rulers upheld their own separate relations with the kingdoms of Nepal and Kashmir, and at times "engaged in armed confrontation with them."[40]

Even though the Yellow Hat sect exchanged gifts with and sent missions to the Ming court up until the 1430s,[71] the Yellow Hat sect was not mentioned in the Mingshi or the Mingshi Lu.[37] On this, historian Li Tieh-tseng says of Tsongkhapa's refusal of Ming invitations to visit Yongle's court:[37]

In China not only the emperor could do no wrong, but also his prestige and dignity had to be upheld at any cost. Had the fact been made known to the public that Ch'eng-tsu's repeated invitations extended to Tsong-ka-pa were declined, the Emperor's prestige and dignity would have been considered as lowered to a contemptible degree, especially at a time when his policy to show high favours toward lamas was by no means popular and had already caused resentment among the people. This explains why no mention of Tsong-k'a-pa and the Yellow Sect was made in the Ming Shih and Ming Shih lu.[37]

Wylie asserts that this type of censorship of the Mingshi distorts the true picture of the history of Sino-Tibetan relations, while the Ming court granted titles to various lamas regardless of their sectarian affiliations in an ongoing civil war in Tibet between competing lamaist factions.[72][73] Wylie argues that Ming titles of "King" granted indiscriminately to various Tibetan lamas or even their disciples should not be viewed as reappointments to earlier Yuan Dynasty offices, since the viceregal Sakya regime established by the Mongols in Tibet was overthrown by the Phagmodru myriarchy before the Ming existed.[74] Helmut Hoffman states that the Ming upheld the facade of rule over Tibet through periodic missions of "tribute emissaries" to the Ming court and by granting nominal titles to ruling lamas, but did not actually interfere in Tibetan governance.[38] Melvyn C. Goldstein writes that the Ming had no real administrative authority over Tibet, as the various titles given to Tibetan leaders did not confer authority as the earlier Mongol Yuan titles had.[39] He asserts that "by conferring titles on Tibetans already in power, the Ming emperors merely recognized political reality."[75] Hugh E. Richardson writes that the Ming Dynasty exercised no authority over the succession of Tibetan ruling families, the Phagmodru (1354–1436), Rinpungpa (1436–1565), and Tsangpa (1565–1642).[76]

Religious significance[editar]

In his usurpation of the throne from the Jianwen Emperor (r. 1398–1402), the Yongle Emperor was aided by the Buddhist monk Yao Guangxiao, and like his father Hongwu, Yongle was "well-disposed towards Buddhism", claims Rossabi.[28] On March 10, 1403, the Yongle Emperor invited Deshin Shekpa (1384–1415), the fifth Karmapa, to his court, even though the fourth Karmapa had rejected the invitation of the Hongwu Emperor of China.[77] A Tibetan translation in the 16th century preserves the letter of Yongle, which the Association for Asian Studies notes is polite and complimentary towards the Karmapa.[77] The letter of invitation read, "My father and both parents of the queen are now dead. You are my only hope, essence of buddhahood. Please come quickly. I am sending as offering a large ingot of silver, one hundred fifty silver coins, twenty rolls of silk, a block of sandalwood, one hundred fifty bricks of tea and ten pounds of incense."[78] In order to seek out the Karmapa, Yongle dispatched his eunuch Hou Xian and the Buddhist monk Zhi Guang (d. 1435) to Tibet.[79] Traveling to Lhasa either through Qinghai or via the Silk Road to Khotan, Hou Xian and Zhi Guang did not return to Nanjing until 1407.[80]

During his travels beginning in 1403, Deshin Shekpa was induced by further exhortations by the Ming court to visit Nanjing by April 10, 1407.[77] Norbu writes that Yongle, following the tradition of Mongol emperors and their reverence for Tibetan Sakya lamas, showed an enormous amount of deference towards Deshin Shekpa. Yongle came out of the palace in Nanjing to greet the Karmapa and did not require him to kowtow like a tributary vassal.[81] According to Karma Thinley, the emperor gave the Karmapa the place of honor at his left, and on a higher throne than his own.[78] Rossabi and others describe a similar arrangement made by Kublai Khan and the Sakya Phagpa lama, writing that Kublai would "sit on a lower platform than the Tibetan cleric" when receiving religious instructions from him.[82][83] Throughout the following month, the Yongle Emperor and his court showered Deshin Shekpa with presents.[78] At Linggu Temple in Nanjing, he presided over the religious ceremonies for Yongle's deceased parents, while twenty-two days of his stay were marked by religious miracles that were recorded in five languages on a gigantic scroll that bore the Emperor's seal.[77][79] During his stay in Nanjing, Deshin Shekpa was bestowed the title "Great Treasure Prince of Dharma" by Yongle.[84] Elliot Sperling asserts that Yongle, in bestowing Deshin Shekpa with the title of "King" and praising his mystical abilities and miracles, was trying to build an alliance with the Karmapa as the Mongols had with the Sakya lamas, but Deshin Shekpa rejected Yongle's offer.[85] In fact, this was the same title that Kublai Khan had offered the Sakya Phagpa lama, but Deshin Shekpa persuaded Yongle to grant the title to religious leaders of other Tibetan Buddhist sects.[66]

Tibetan sources say Deshin Shekpa also persuaded Yongle not to impose his military might on Tibet as the Mongols had previously done.[77] Thinley writes, before Deshin Shekpa returned to Tibet, the emperor began planning to send a military force into Tibet to forcibly give the Karmapa authority over all the Tibetan Buddhist sects, but Deshin Shekpa dissuaded him.[86] But Hok-Lam Chan states that "there is little evidence that this was ever the emperor's intention" and that evidence indicates that Deshin Skekpa was invited strictly for religious purposes.[71]

Marsha Weidner states that Deshin Shekpa's miracles "testified to the power of both the emperor and his guru and served as a legitimizing tool for the emperor's problematic succession to the throne," referring to Yongle's conflict with the previous Jianwen Emperor.[87] Tsai writes that Deshin Shekpa aided the legitimacy of Yongle's rule by providing him with portents and omens which demonstrated Heaven's favor of Yongle on the Ming throne.[79]

With the example of the Ming court's relationship with the fifth Karmapa and other Tibetan leaders, Norbu states that Chinese Communist historians have failed to realize the significance of the religious aspect of the Ming-Tibetan relationship.[88] He writes that the meetings of lamas with the emperor were exchanges of tribute between "the patron and the priest" and were not merely instances of a political subordinate paying tribute to a superior.[88] He also notes that the items of tribute were Buddhist artifacts which symbolized "the religious nature of the relationship."[88] Josef Kolmaš writes that the Ming Dynasty did not exercise any direct political control over Tibet, content with their tribute relations that were "almost entirely of a religious character."[89] Patricia Ann Berger writes that Yongle's courting and granting of titles to lamas was his attempt to "resurrect the relationship between China and Tibet established earlier by the Yuan dynastic founder Khubilai Khan and his guru Phagpa."[47] She also writes that the later Qing emperors and their Mongol associates viewed Yongle's relationship with Tibet as "part of a chain of reincarnation that saw this Han Chinese emperor as yet another emanation of Manjusri."[47]

The Information Office of the State Council of the PRC preserves an edict of the Zhengtong Emperor (r. 1435–1449) addressed to the Karmapa in 1445, written after the latter's agent had brought holy relics to the Ming court.[90] Zhengtong had the following message delivered to the Great Treasure Prince of Dharma, the Karmapa:[90]

Out of compassion, Buddha taught people to be good and persuaded them to embrace his doctrines. You, who live in the remote Western Region, have inherited the true Buddhist doctrines. I am deeply impressed not only by the compassion with which you preach among the people in your region for their enlightenment, but also by your respect for the wishes of Heaven and your devotion to the Court. I am very pleased that you have sent bSod-nams-nyi-ma and other Tibetan monks here bringing with them statues of Buddha, horses and other specialties as tributes to the court.[90]

Despite this glowing message by Zhengtong, Chan writes that in 1446 the Ming court cut off all relations with the Karmapa hierarchs.[71] Until that year, the Ming court was unaware that Deshin Shekpa had died in 1415.[71] Before discovering this, the Ming court believed that the representatives of his sect who continued to visit the Ming capital were sent by him.[71]

Tribute and exchanging tea for horses[editar]

Tsai writes that shortly after the visit by Deshin Shekpa, Yongle ordered the construction of a road and trading posts at the upper reaches of the Yangzi River and Mekong River in order to facilitate trade with Tibet in tea, horses, and salt.[80] The trade route passed through Sichuan and crossed Shangri-La County in Yunnan.[80] Wang and Nyima assert that this "tribute-related trade" of the Ming exchanging Chinese tea for Tibetan horses—while granting Tibetan envoys and Tibetan merchants explicit permission to trade with Han Chinese merchants—"furthered the rule of the Ming Dynasty court over Tibet".[92] Rossabi and Sperling note that this trade in Tibetan horses for Chinese tea existed long before the Ming was established.[30][93] Peter C. Perdue says that obtaining horses from Inner Asia in exchange for Chinese tea was also the goal of the earlier Wang Anshi (1021–1086), who realized that China could not produce enough militarily capable steeds.[94] Horses were needed not only for cavalry but also as draft animals for the army's supply wagons.[94] The Tibetans required Chinese tea not only as a common beverage but also as a religious ceremonial supplement.[30] The Ming government imposed a monopoly on tea production and attempted to regulate this trade with state-supervised markets, but these collapsed in 1449 due to military failures and internal ecological and commercial pressures on the tea producing regions.[30][94]

Van Praag states that the Ming's establishment of diplomatic delegations with Tibet was merely an effort by the Ming court to secure urgently needed horses.[95] Wang and Nyima argue that these were not diplomatic delegations at all, that Tibetan areas were ruled by the Ming since Tibetan leaders were granted positions as Ming officials, that horses were collected from Tibet as a mandatory "corvée" tax, and therefore Tibetans were "undertaking domestic affairs, not foreign diplomacy".[96] Sperling writes that the Ming simultaneously bought horses in the Kham region while fighting Tibetan tribes in Amdo and receiving Tibetan embassies in Nanjing.[27] He also argues that the embassies of Tibetan lamas visiting the Ming court were for the most part efforts to promote commercial transactions between the lamas' large, wealthy entourage and Ming Chinese merchants and officials.[97] Kolmaš writes that while the Ming maintained a laissez-faire policy towards Tibet and limited the numbers of the Tibetan retinues, the Tibetans sought to maintain a tributary relationship with the Ming because imperial patronage provided them with wealth and power.[98] Laird writes that Tibetans eagerly sought Ming court invitations since the gifts the Tibetans received for bringing tribute were much greater in value than the latter.[99] As for Yongle's gifts to his Tibetan and Nepalese vassals such as silver wares, Buddha relics, utensils for Buddhist temples and religious ceremonies, and gowns and robes for monks, Tsai writes "in his effort to draw neighboring states to the Ming orbit so that he could bask in glory, Yongle was quite willing to pay a small price."[100] The Information Office of the State Council of the PRC lists the Tibetan tribute items as oxen, horses, camels, sheep, fur products, medical herbs, Tibetan incenses, thangkas (painted scrolls), and handicrafts while the Ming awarded Tibetan tribute-bearers with an equal value of gold, silver, satin and brocade, bolts of cloth, grains, and tea leaves.[1] Silk workshops during the Ming also catered specifically to the Tibetan market with silk clothes and furnishings featuring Tibetan Buddhist iconography.[91]

While the Ming Dynasty traded horses with Tibet, it upheld a policy of outlawing border markets in the north, which Laird says was an effort to punish the Mongols for their raids and to "drive them from the frontiers of China."[101] However, when Altan Khan (1507–1582)—leader of the Tümed Mongols who overthrew the Oirat Mongol confederation's hegemony over the steppes—made peace with the Ming Dynasty in 1571, he persuaded the Ming to reopen their border markets in 1573.[101] This provided the Chinese with a new supply of horses that the Mongols had in excess; it was also a relief to the Ming, since they were unable to stop the Mongols from periodic raiding.[101] Laird says that despite the fact that later Mongols believed Altan forced the Ming to view him as an equal, Chinese historians argue that he was simply a loyal Chinese citizen.[101] By 1578, Altan Khan formed a formidable Mongol-Tibetan alliance with the Yellow Hat sect that the Ming viewed from afar without intervention.[102][103][104]

Intervención armada y estabilidad fronteriza[editar]

Patricia Ebrey escribe que el Tíbet, al igual que el territorio bajo la Dinastía Joseon y otros estados vecinos al régimen Ming, aceptó su situación tributaria mientras no hubiese tropas o gobernantes de la China Ming instalados en su territorio.[105] Laird escribe que «después de que las tropas mongolas abandonaron el Tíbet, ninguna tropa Ming los remplazó».[68] Wang y Nyima aseguran que, a pesar del hecho de que la Dinastía Ming se abstuvo de enviar tropas para someter al Tíbet y evitó colocarlas ahí, esas medidas eran innecesarias siempre que la corte Ming sostuviera vínculos estrechos con los vasallos tibetanos y sus fuerzas.[35] No obstante, hubo momentos en el siglo XIV en los que el emperador Hongwu utilizó la fuerza militar para apaciguar rebeliones en el Tíbet. John D. Langlois escribe que existían tumultos en el Tíbet y en la parte occidental de Sichuan. El marqués Mu Ying (沐英) había sido comisionado para calmar dichos tumultos en noviembre de 1378 después de que estableció un Taozhou en Gansu.[106] Langlois apunta que para octubre de 1379. Mu Ying había capturado supuestamente 30.000 prisioneros tibetanos y 200.000 animales domésticos.[106] Aun así la invasión ocurrió de ambas maneras; al general Ming Qu Neng, bajo el mando de Lan Yu, se le ordenó repeler un asalto tibetano a Sichuan en 1390.[107]

Las discusiones de estrategias en la mitad del periodo de la Dinastía Ming se enfocaron principalmente en la recuperación de la región de Ordos, la cual había sido utilizada por los mongoles como base de reunión para iniciar incursiones hacia la China Ming.[108] Norbu menciona que la Dinastía Ming, preocupada por la amenaza que suponían los mongoles en el norte, no pudo enviar fuerzas armadas adicionales para asegurar o reforzar su pretensión de soberanía sobre el Tíbet. En vez de ello, confiaron en los "instrumentos de Confucio de relaciones tributarias" que concedían un número ilimitado de títulos y ibsequios a los lamas tibetanos a través de acciones diplomáticas.[109] Sperling asegura que la delicada relación entre la dinastía Ming y el Tíbet era "la última ocasión en que una China unida tendría que tratar con un Tíbet independiente", que no había posibilidad de un conflicto armado en sus fronteras y que el fin último de la política exterior Ming con el Tíbet no era una subyugación, sino "la evitación de cualquier clase de trato con los tibetanos".[110] P. Christiaan Klieger argumenta que el patronazgo de la corte Ming de los altos lamas Tibetanos "estaba diseñada para ayudar a estabilizar las regiones fronterizas y proteger las rutas comerciales".[111]

Los historiadores Luciano Petech y Sato Hisahi mencionan que la dinastía Ming mantuvo una política de «división y mando» envías de crear un Tíbet débil y políticamente fragmentado después de que el régimen Sakya hubiera caído.[67] Chan escribe que esto era quizá la estrategia calculada de Yongle, dado que un patronazgo exclusivo a una única secta Tibetana le habría dado demasiado poder regional.[112] Sperling no encuentra evidencia textual tanto en fuentes chinas o tibetanas para apoyar esta tesis de Petech y Hisahi.[67] Norbu asegura que su tesis está principalmente basada en la lista de títulos Ming concedidos a los lamas tibetanos más que en un «análisis comparativo de desarrollos en China y el Tíbet».[67] Rossabi menciona que esta teoría «atribuye demasiado influencia a los chinos», resaltando el hecho de que el Tíbet se encontraba ya políticamente dividido cuando la Dinastía Ming comenzó.[30] Rossabi excluye también la teoría de «división y mando» en los cimientos del intento fallido de Yongle de construir una relación fuerte con el quinto Karmapa, del cual él esperaba que igualara la anterior relación de Kublai Khan con el lama Sakya Phagpa.[66] En vez de ello, Yongle siguió el consejo del Karmapa de dar patronazgo a muchos diferentes lamas tibetanos.[66]

The Association for Asian Studies states that there is no known written evidence to suggest that later leaders of the Yellow Hat sect—First Dalai Lama Gendun Drup (1391–1474) and Second Dalai Lama Gendun Gyatso (1475–1571)—had any contacts with Ming China.[113] These two religious leaders were preoccupied with an overriding concern for dealing with the powerful secular princes of Rinbung, who were patrons and protectors of the Black Hat Karmapa lamas.[113] The Rinbung (Rinpungpa) leaders were relatives of the Phagmodru, yet their authority shifted over time from simple governors to rulers in their own right over large areas of Ü-Tsang.[114] The prince of Rinbung occupied Lhasa in 1498 and excluded the Yellow Hat sect from attending New Years ceremonies and prayers, the most important event in the Yellow Hat sect.[115] While the task of New Years prayers in Lhasa was granted to the Karmapa and others, Gendun Gyatso traveled in exile looking for allies.[115] However, it was not until 1518 that the secular Phagmodru ruler captured Lhasa from the Rinbung, and thereafter the Yellow Hat sect was given rights to conduct the New Years prayer.[115] When the Red Hat abbot of the Drigung Monastery threatened Lhasa in 1537, Gendun Gyatso was forced to abandon the Drepung Monastery, although he eventually returned.[115]

The Zhengde Emperor (r. 1505–1521), who enjoyed the company of lamas at court despite protests from the censorate, had heard tales of a "living Buddha" which he desired to host at the Ming capital; this was none other than the Rinbung-supported Karmapa then occupying Lhasa.[116] Zhengde's top advisors made every attempt to dissuade him from inviting this lama to court, arguing that Tibetan Buddhism was wildly heterodox and unorthodox.[29] Despite protests by the Grand Secretary Liang Chu, in 1515 the Zhengde Emperor sent his eunuch official Liu Yun of the palace chancellery on a mission to invite this Karmapa to Beijing.[117] Liu commanded a fleet of hundreds of ships requisitioned along the Yangzi River, consuming 2,835 g (100 oz) of silver a day in food expenses while stationed for a year in Chengdu of Sichuan.[118] After procurring necessary gifts for the mission, he departed with a cavalry force of about 1,000 troops.[118] When the request was delivered, the Karmapa lama refused to leave Tibet despite the Ming force brought to coerce him.[118] The Karmapa launched a surprise ambush on Liu Yun's camp, seizing all the goods and valuables while killing or wounding half of Liu Yun's entire escort.[118] After this fiasco, Liu fled for his life, but only returned to Chengdu several years later to find that the Zhengde Emperor had died.[118]

Tibetans as a "national minority"[editar]

Elliot Sperling, a specialist of Indian studies and the director of the Tibetan Studies program at Indiana University’s Department of Central Eurasia Studies, writes that "the idea that Tibet became part of China in the 13th century is a very recent construction."[120] He writes that Chinese writers of the early 20th century were of the view that Tibet was not annexed by China until the Manchu Qing Dynasty invasion during the 18th century.[120] He also states that Chinese writers of the early 20th century described Tibet as a feudal dependent of China, not an integral part of it.[120] Sperling states that this is because "Tibet was ruled as such, within the empires of the Mongols and the Manchus" and also that "China's intervening Ming Dynasty ... had no control over Tibet."[120] He writes that the Ming relationship with Tibet is problematic for China’s insistence of its unbroken sovereignty over Tibet since the 13th century.[120] As for the Tibetan view that Tibet was never subject to the rule of the Yuan or Qing emperors of China, Sperling also discounts this by stating that Tibet was "subject to rules, laws and decisions made by the Yuan and Qing rulers" and that even Tibetans described themselves as subjects of these emperors.[120]

Josef Kolmaš, a sinologist, Tibetologist, and Professor of Oriental Studies at the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, writes that it was during the Qing Dynasty "that developments took place on the basis of which Tibet came to be considered an organic part of China, both practically and theoretically subject to the Chinese central government."[121] Yet he states that this was a radical change in regards to all previous eras of Sino-Tibetan relations.[121]

P. Christiaan Klieger, an anthropologist and scholar of the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, writes that the vice royalty of the Sakya regime installed by the Mongols established a patron-priest relationship between Tibetans and Mongol converts to Tibetan Buddhism.[111] According to him, the Tibetan lamas and Mongol khans upheld a "mutual role of religious prelate and secular patron," respectively.[111] He adds that "Although agreements were made between Tibetan leaders and Mongol khans, Ming and Qing emperors, it was the Republic of China and its Communist successors that assumed the former imperial tributaries and subject states as integral parts of the Chinese nation-state."[111]

Marina Illich, a scholar of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, while discussing the life of the Yellow Hat lama Chankya Rolpe Dorje (1717–1786), mentions the limitations of both Western and Chinese modern scholarship in their interpretation of Tibetan sources. As for the limitations imposed on scholars by the central government of the People's Republic of China on issues regarding the history of Tibet, Illich writes:[119]

PRC scholars ... work under the strict supervision of censor bureaus and must adhere to historiographic guidelines issued by the state [and] have little choice but to frame their discussion of eighteenth-century Tibetan history in the anachronistic terms of contemporary People's Republic of China (P.R.C.) state discourse ... Bound by Party directives, these scholars have little choice but to portray Tibet as a trans-historically inalienable part of China in a way that profoundly obscures questions of Tibetan agency.[119]

China Daily, a CCP-controlled news organization since 1981, states that although there were dynastic changes after Tibet was incorporated into the territory of China's Yuan Dynasty in the 13th century, "Tibet has remained under the jurisdiction of the central government of China."[122] It also states that the Ming Dynasty "inherited the right to rule Tibet" from the Yuan Dynasty, and repeats the claims in the Mingshi about the Ming establishing two itinerant high commands over Tibet.[122] China Daily states that the Ming handled Tibet's civil administration, appointed all leading officials of these administrative organs, and punished Tibetans who broke the law.[122] The party-controlled People's Daily, the state-controlled Xinhua News Agency, and the state-controlled national television network China Central Television post the same article that China Daily has, the only difference being their headlines and some additional text.[123][124][125]

Mongol-Tibetan alliance[editar]

Altan Khan and the Dalai Lama[editar]

During the reign of the Jiajing Emperor (r. 1521–1567), the native Chinese ideology of Daoism was fully sponsored at the Ming court, while the Tibetan Buddhism of Tibet's lamas and even other types of Buddhism were ignored or suppressed.[37] Even the Mingshi states that the Tibetan lamas discontinued their trips to Ming China and its court at this point.[37] The Grand Secretary Yang Tinghe under Jiajing was determined to break the eunuch influence at court which typified the Zhengde era,[126] an example being the costly escort of the eunuch Liu Yun as described above in his failed mission to Tibet. The court eunuchs were in favor of expanding and building new commercial ties with foreign countries such as Portugal, which Zhengde deemed permissible since he had an affinity for foreign and exotic people.[126] With the death of Zhengde and ascension of Jiajing, the politics at court shifted in favor of the Confucian establishment which not only rejected the Portuguese embassy of Fernão Pires de Andrade (d. 1523),[126] but had a predisposed animosity towards Tibetan Buddhism and lamas.[117] Evelyn S. Rawski, a professor in the Department of History of the University of Pittsburgh, writes that the Ming's unique relationship with Tibetan prelates essentially ended with Jiajing's reign while Ming influence in the Amdo region was supplanted by the Mongols.[127]

Meanwhile, the Tümed Mongols began moving into the Kokonor region (modern Qinghai province), raiding the Ming Chinese frontier and even as far as the suburbs of Beijing under Altan Khan (1507–1582).[37][128] Klieger writes that Altan Khan's presence in the west effectively reduced Ming influence and contact with Tibet.[129] After Altan Khan made peace with the Ming Dynasty in 1571, he invited the third hierarch of the Yellow Hat sect—Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588)—to meet him in Amdo (modern Qinghai) in 1578, where he accidentally bestowed him and his two predecessors with the title of Dalai Lama—literally "Ocean Teacher".[37][130] The full title was "Dalai Lama Vajradhara", vajradhara meaning "Holder of the Thunderbolt" in Sanskrit.[130][131] Victoria Huckenpahler notes that the vajradhara is considered by Buddhists to be the primordial Buddha of limitless and all-pervasive beneficial qualities, a being that "represents the ultimate aspect of enlightenment."[132] Goldstein writes that Sonam Gyatso also enhanced Altan Khan's standing by granting him the title "king of religion, majestic purity".[102] Rawski writes that the Dalai Lama officially recognized Altan Khan as the "Protector of the Faith".[133]

Laird writes that Altan Khan abolished the native Mongol practices of shamanism and blood sacrifice, while the Mongol princes and subjects were coerced by Altan to convert to Tibetan Gelug Buddhism—or face execution if they persisted in their shamanistic ways.[134] Committed to their religious leader, Mongol princes began requesting the Dalai Lama to bestow titles on them, which demonstrated "the unique fusion of religious and political power" wielded by the Dalai Lama, as Laird writes.[135] Kolmaš states that the spiritual and secular Mongol-Tibetan alliance of the 13th century was renewed by this alliance constructed by Altan Khan and Sonam Gyatso.[136] Van Praag writes that this restored the original Mongol patronage of a Tibetan lama and "to this day, Mongolians are among the most devout followers of the Gelugpa and the Dalai Lama."[137] Angela F. Howard writes that this unique relationship not only provided the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama with religious and political authority in Tibet, but that Altan Khan gained "enormous power among the entire Mongol population."[138] Rawski writes that Altan Khan's conversion to the Yellow Hat sect "can be interpreted as an attempt to expand his authority in his conflict with his nominal superior, Tümen Khan."[133] To further cement the Mongol-Tibetan alliance, the great-grandson of Altan Khan—Yonten Gyatso (1589–1616)—was made the fourth Dalai Lama.[37][131] In 1642, the fifth Dalai Lama Lozang Gyatso (1617–1682) became the first to wield effective political control over Tibet.[60]

Contact with the Ming Dynasty[editar]

Sonam Gyatso, after being granted the grandiose title by Altan Khan, departed for Tibet. Before he left, he sent a letter and gifts to the Ming Chinese official Zhang Juzheng (1525–1582), which arrived on March 12, 1579.[139] Sometime in August or September of that year, Sonam Gyatso's representative stationed with Altan Khan received a return letter and gift from the Wanli Emperor (r. 1572–1620), who also conferred upon Sonam Gyatso a title; this was the first official contact between a Dalai Lama and a government of China.[139] However, Laird states that when Wanli invited him to Beijing, the Dalai Lama declined the offer due to a prior commitment, even though he was only 400 km (250 miles) from Beijing.[135] Laird adds that "the power of the Ming emperor did not reach very far at the time."[135] Although not recorded in any official Chinese records, Sonam Gyatso's biography states that Wanli again conferred titles on Sonam Gyatso in 1588, and invited him to Beijing for a second time, but Sonam Gyatso was unable to visit China as he died in Mongolia while en route to Tibet[cita requerida], after working since 1585 with Altan Khan's son in Mongolia to further the spread of Buddhism.[135][139]

Of the third Dalai Lama, China Daily states that the "Ming Dynasty showed him special favor by allowing him to pay tribute."[122] China Daily then says that Sonam Gyatso was granted the title Dorjichang or Vajradhara Dalai Lama in 1587 [sic!],[122] but China Daily does not mention who granted him the title. Without mentioning the role of the Mongols, China Daily states that it was the successive Qing Dynasty which established the title of Dalai Lama and his power in Tibet: "In 1653, the Qing emperor granted an honorific title to the fifth Dalai Lama and then did the same for the fifth Bainqen Lama in 1713, officially establishing the titles of the Dalai Lama and the Bainqen Erdeni, and their political and religious status in Tibet."[122]

Chen states that the fourth Dalai Lama Yonten Gyatso was granted the title "Master of Vajradhara" and an official seal by the Wanli Emperor in 1616.[140] This was noted in the Biography of the Fourth Dalai Lama, which stated that one Soinam Lozui delivered the seal of the Emperor to the Dalai Lama.[140] The Wanli Emperor had invited Yonten Gyatso to Beijing in 1616, but just like his predecessor he died before being able to make the journey.[140]

Kolmaš writes that, as the Mongol presence in Tibet increased, culminating in the conquest of Tibet by a Mongol leader in 1642, the Ming emperors "viewed with apparent unconcern these developments in Tibet."[103] He adds that the Ming court's lack of concern for Tibet was one of the reasons why the Mongols pounced on the chance to reclaim their old vassal of Tibet and "fill once more the political vacuum in that country."[89] On the mass Mongol conversion to Tibetan Buddhism under Altan Khan, Laird writes that "the Chinese watched these developments with interest, though few Chinese ever became devout Tibetan Buddhists."[104]

Civil war and Güshi Khan's conquest[editar]

In 1565, the powerful Rinbung princes were overthrown by one of their own ministers, who styled himself as the Tsangpa or Ü-Tsang king and established his base of power at Shigatse.[76][130][141] The second successor of this first Ü-Tsang king took control of the whole of Central Tibet, reigning from 1611–1621.[142] Despite this, the leaders of Lhasa still claimed their allegiance to the Phagmodru as well as the Yellow Hat sect, while the Ü-Tsang king allied with the Karmapa.[142] Tensions rose between the nationalistic Ü-Tsang ruler and the Mongols who safeguarded their Mongol Dalai Lama in Lhasa.[130] The fourth Dalai Lama refused to give an audience to the Ü-Tsang king, which sparked a conflict as the latter began assaulting Yellow Hat monasteries.[130] Chen writes of the speculation over the fourth Dalai Lama's mysterious death and the plot of the Ü-Tsang king to have him murdered for "cursing" him with illness, although Chen writes that the murder was most likely the result of a feudal power struggle.[143] In 1618, only two years after Yonten Gyatso died, the Yellow Hat sect and the Red Hat sect went to war, the Red Hats supported by the secular Ü-Tsang king.[144] The Ü-Tsang ruler had a large number of Yellow Hat lamas killed, occupied their monasteries at Drepung and Sera, and outlawed any attempts to find another Dalai Lama.[144] In 1621, the Ü-Tsang king died and was succeeded by his young son, an event which stymied the war effort as the latter accepted the six-year-old Lozang Gyatso as the new Dalai Lama.[130] Despite the new Dalai Lama's diplomatic efforts to maintain friendly relations with the new Ü-Tsang ruler, Sonam Chöpel (1595–1657), the Dalai Lama's chief steward and treasurer at Drepung, made efforts to overthrow the Ü-Tsang king, which led to another conflict.[145] In 1633, the Yellow Hats and several thousand Mongol adherents defeated the Ü-Tsang king's troops near Lhasa before a peaceful negotiation was settled.[144] Goldstein writes that in this the "Mongols were again playing a significant role in Tibetan affairs, this time as the military arm of the Dalai Lama."[144]

When an ally of the Ü-Tsang ruler threatened destruction of the Yellow Hats again, the fifth Dalai Lama Lozang Gyatso pleaded for help from the Mongol prince Güshi Khan (1582–1655), leader of the Khoshut (Qoshot) tribe of the Oirat Mongols, who was then on a pilgrimage to Lhasa.[131][146][147][148] Güshi Khan accepted his role as protector, and from 1637–1640 he not only defeated the Yellow Hats' enemies in the Amdo and Kham regions, but also resettled his entire tribe into Amdo.[131][146] Sonam Chöpel urged Güshi Khan to assault the Ü-Tsang king's homebase of Shigatse, which Güshi Khan agreed upon, enlisting the aid of Yellow Hat monks and supporters.[146][148] In 1642, after a year's siege of Shigatse, the Ü-Tsang forces surrendered.[148] Güshi Khan then captured and summarily executed the ruler of Ü-Tsang, King of Tibet.[146][147]

Soon after the victory in Ü-Tsang, Güshi Khan organized a welcoming ceremony for Lozang Gyatso once he arrived a day's ride from Shigatse, presenting his conquest of Tibet as a gift to the Dalai Lama.[148] In a second ceremony held within the main hall of the Shigatse fortress, Güshi Khan enthroned the Dalai Lama as the ruler of Tibet, but conferred the actual governing authority to the regent Sonam Chöpel.[146][147][148] Although Güshi Khan had granted the Dalai Lama "supreme authority" as Goldstein writes, the title of 'King of Tibet' was conferred upon Güshi Khan, spending his summers in pastures north of Lhasa and occupying Lhasa each winter.[103][146][149] Van Praag writes that at this point Güshi Khan maintained control over the armed forces, but accepted his inferior status towards the Dalai Lama.[149] Rawski writes that the Dalai Lama shared power with his regent and Güshi Khan during his early secular and religious reign.[150] However, Rawski states that he eventually "expanded his own authority by presenting himself as Avalokitesvara through the performance of rituals," by building the Potala Palace and other structures on traditional religious sites, and by emphasizing lineage reincarnation through written biographies.[151] Goldstein states that the government of Güshi Khan and the Dalai Lama persecuted the Black Hat Karma Kagyu sect, confiscated their wealth and property, and even converted their monasteries into Yellow Hat Gelug monasteries.[146] Rawski writes that this Mongol patronage allowed the Yellow Hats to dominate the rival religious sects in Tibet.[151]

Meanwhile, the Chinese Ming Dynasty fell to the rebellion of Li Zicheng (1606–1645) in 1644, yet his short-lived Shun Dynasty was crushed by the Manchu invasion and the Han Chinese general Wu Sangui (1612–1678). China Daily states that when the following Qing Dynasty replaced the Ming Dynasty, it merely "strengthened administration of Tibet."[122] However, Kolmaš states that the Dalai Lama was very observant of what was going on in China and accepted a Manchu invitation in 1640 to send envoys to their capital at Mukden in 1642, before the Ming collapsed.[152][153] Dawa Norbu, William Rockhill, and George N. Patterson write that when the Shunzhi Emperor (r. 1644–1661) of the subsequent Qing Dynasty invited the fifth Dalai Lama Lozang Gyatso to Beijing in 1652, Shunzhi treated the Dalai Lama as an independent sovereign of Tibet.[88][154] Patterson writes that this was an effort of Shunzhi to secure an alliance with Tibet that would ultimately lead to the establishment of Manchu rule over Mongolia.[154] In this meeting with the Qing emperor, Goldstein asserts that the Dalai Lama was not someone to be trifled with due to his alliance with Mongol tribes, some of which were declared enemies of the Qing.[155] Van Praag states that Tibet and the Dalai Lama's power was recognized by the "Manchu Emperor, the Mongolian Khans and Princes, and the rulers of Ladakh, Nepal, India, Bhutan, and Sikkim."[153]

When the Dzungar Mongols attempted to spread their territory from what is now Xinjiang into Tibet, the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661–1722) responded to Tibetan pleas for aid with his own invasion of Tibet in 1717, occupying Lhasa in 1720.[105][156] By 1751, during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796), a protectorate and permanent Qing Dynasty garrison was established in Tibet.[105][156] As of 1751, Albert Kolb writes that "Chinese claims to suzerainty over Tibet date from this time."[156]

Administrative offices and officials' titles[editar]

| Divisiones administrativas Ming establecidas en el Tíbet de acuerdo al Mingshi.[33] | |

|---|---|

| Alta Comandancia Itinerante (都指揮使司) | Dbus-Gtsang (烏思藏), Mdo-khams (朵甘) |

| Comandancia Itinerante (指揮使司) | Longda (隴答) |

| Comisionado de la Oficina de Pacificación (宣尉使司) | Duogan (朵甘), Dongbuhanhu (董卜韓胡), Changhexiyutongningyuan (長河西魚通寧遠) |

| Comisionado de la Oficina de Expedición (招討司) | Duogansi (朵甘思), Duoganlongda (朵甘隴答), Duogandan (朵甘丹), Duogancangtang (朵甘倉溏), Duoganchuan (朵甘川), Moerkan (磨兒勘) |

| Oficinas Wanhu (萬戶府) | Shaerke (沙兒可), Naizhu (乃竹), Luosiduan (羅思端), Biesima (別思麻) |

| Oficinas Qianhu (千戶所) | Duogansi (朵甘思), Suolazong (所剌宗), Suobolijia (所孛里加), Suochanghexi (所長河西), Suoduobasansun (所多八三孫), Suojiaba (所加八), Suozhaori (所兆日), Nazhu (納竹), Lunda (倫答), Guoyou (果由), Shalikehahudi (沙里可哈忽的), Bolijiasi (孛里加思), Shalituer (撒裏土兒), Canbulang (參卜郎), Lacuoya (剌錯牙), Xieliba (泄里壩), Runzelusun (潤則魯孫) |

| Títulos Ming otorgados a los líderebes tibetanos. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Título | Nombre | Secta | Año | |

| Príncipes del Dharma (法王) | Gran Tesoro del Príncipe del Dharma (大寶法王) | Tulku Tsurphu Karmapa[84] | Secta Karma Kagyu (Secta del «Black Hat») | 1407 |

| Gran Vehículo del Príncipe del Dharma (大乘法王) | Príncipe del Dharma de la secta Sagya (representada por Gunga Zhaxi)[84] | Secta Sagya (Secta Red Hat) | 1413 | |

| Gran Misericordia del Príncipe del Dharma (大慈法王) | Shākya Yeshes (representante del Je Tsongkhapa)[84] | Secta Gelug (Secta Yellow Hat) | 1434 | |

| Princes (王) | Princípe de la Persuasión (闡化王) | Zhaba Gyaincain[157] | Secta Phagmo Drupa | 1406 |

| Promoción del Príncipe de la Virtud (贊善王) | Zhusibar Gyaincain[157] | Lingzang | 1407 | |

| Príncipe Guardián de la Doctrina (護教王) | Namge Bazangpo[64] | Guanjor | 1407 | |

| Propagación del Príncipe de la Doctrina (闡教王) | Linzenbal Gyangyanzang[84] | Secta Zhigung Gagyu | 1413 | |

| Asistente del Príncipe de la Doctrina (輔教王) | Namkelisiba (Namkelebei Lobzhui Gyaincain Sangpo)[64] | Secta Sagya | 1415 | |

See also[editar]

- Tibetan sovereignty debate

- Foreign relations of Imperial China

- Foreign relations of Tibet

- History of China

- History of Tibet

Notes[editar]

- [158] Chinese: 俄力思軍民元帥府

- [159] Chinese: 烏思藏都指揮使司

- [160] Chinese: 朵甘衛都指揮使司

- [161] Chinese: 指揮使司

- [162] Chinese: 宣尉使司

- [163] Chinese: 招討司

- [164] Chinese: 萬戶府

- [165] Chinese: 千戶所

References[editar]

- ↑ a b c d Information Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China, Testimony of History (China Intercontinental Press, 2002), 73.

- ↑ Wang Jiawei & Nyima Gyaincain, The Historical Status of China's Tibet (China Intercontinental Press, 1997), 39–41.

- ↑ Melvyn C. Goldstein, Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet and the Dalai Lama (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 1.

- ↑ Denis Twitchett, "Tibet in Tang's Grand Strategy", in Warfare in Chinese History (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2000), 106–179.

- ↑ Michael C. van Walt van Praag, The Status of Tibet: History, Rights, and Prospects in International Law (Boulder: Westview Press, 1987), 1–2.

- ↑ Josef Kolmas, Tibet and Imperial China: A Survey of Sino-Tibetan Relations Up to the End of the Manchu Dynasty in 1912: Occasional Paper 7 (Canberra: The Australian National University, Centre of Oriental Studies, 1967), 12–14.

- ↑ a b Van Praag, The Status of Tibet, 4.

- ↑ a b Kolmas, Tibet and Imperial China, 14–17.

- ↑ a b c d e Van Praag, The Status of Tibet, 5.

- ↑ Hok-Lam Chan, "The Chien-wen, Yung-lo, Hung-shi, and Hsuan-te reigns", in The Cambridge History of China: Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644, Part 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 261.

- ↑ Goldstein, The Snow Lion and the Dragon, 2–3.

- ↑ a b c Goldstein, The Snow Lion and the Dragon, 3.

- ↑ Morris Rossabi, Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 18.

- ↑ Rossabi, Khubilai Khan, 14–41.

- ↑ a b Rossabi, Khubilai Khan, 40–41.

- ↑ George N. Patterson, "China and Tibet: Background to the Revolt", The China Quarterly, no. 1 (January-March 1960): 88.

- ↑ a b c d e f Van Praag, The Status of Tibet, 6.

- ↑ a b Patterson, "China and Tibet", 88–89.

- ↑ Turrell V. Wylie, "The First Mongol Conquest of Tibet Reinterpreted", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 37, no. 1 (June 1997): 104.

- ↑ a b c Van Praag, The Status of Tibet, 6–7.

- ↑ a b Rossabi, Khubilai Khan, 115.

- ↑ Denis Twitchett, Herbert Franke, John K. Fairbank, in The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 454.

- ↑ a b c d e f Chan, "The Chien-wen, Yung-lo, Hung-shi, and Hsuan-te reigns", 262.

- ↑ a b Goldstein, The Snow Lion and the Dragon, 4.

- ↑ Patricia B. Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 190–191.

- ↑ Morris Rossabi, "The Ming and Inner Asia," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 242–243.

- ↑ a b c Elliot Sperling, "The 5th Karma-pa and some aspects of the relationship between Tibet and the Early Ming", in The History of Tibet: Volume 2, The Medieval Period: c. AD 850–1895, the Development of Buddhist Paramountcy (New York: Routledge, 2003), 475.

- ↑ a b c Rossabi, "The Ming and Inner Asia," 242.

- ↑ a b c Gray Tuttle, Tibetan Buddhists in the Making of Modern China (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 27.

- ↑ a b c d e Rossabi, "The Ming and Inner Asia," 243.

- ↑ Mingshi-Geography I «明史•地理一»: 東起朝鮮,西據吐番,南包安南,北距大磧。

- ↑ Mingshi-Geography III «明史•地理三»: 七年七月置西安行都衛於此,領河州、朵甘、烏斯藏、三衛。

- ↑ a b Mingshi-Military II «明史•兵二»

- ↑ Mingshi-Western territory III «明史•列傳第二百十七西域三»

- ↑ a b Wang & Nyima, The Historical Status of China's Tibet, 38.

- ↑ a b Van Praag, The Status of Tibet, 7.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Turrell V. Wylie, "Lama Tribute in the Ming Dynasty", in The History of Tibet: Volume 2, The Medieval Period: c. AD 850–1895, the Development of Buddhist Paramountcy (New York: Routledge, 2003), 470.

- ↑ a b Helmut Hoffman, "Early and Medieval Tibet", in The History of Tibet: Volume 1, The Early Period to c. AD 850, the Yarlung Dynasty (New York: Routledge, 2003), 65.

- ↑ a b Goldstein, The Snow Lion and the Dragon, 4–5.

- ↑ a b c Van Praag, The Status of Tibet, 8.

- ↑ a b c d Wang & Nyima, The Historical Status of China's Tibet, 31.

- ↑ Van Praag, The Status of Tibet, 7–8.

- ↑ Wang & Nyima, The Historical Status of China's Tibet, 32.

- ↑ a b Wang & Nyima, The Historical Status of China's Tibet, 37.

- ↑ Thomas Laird, The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama (New York: Grove Press, 2006), 106–107.

- ↑ a b Laird, The Story of Tibet, 107.

- ↑ a b c Patricia Ann Berger, Empire of Emptiness: Buddhist Art and Political Authority in Qing China (Manoa: University of Hawaii Press, 2003), 184.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition (2001-07). Yuan. Consultado el 2008-04-28.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Americana. (2008). Grolier Online. "Hucker, Charles H. "Yüan Dynasty" Consultado el 2008-04-28.

- ↑ a b The Metropolitan Museum of Art. "Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368)". En Timeline of Art History. Consultado el 28 de abril de 2008.

- ↑ Rossabi, Khubilai Khan, 56.

- ↑ Rossabi, Khubilai Khan, 30, 71–72, 117, 130.

- ↑ Rossabi, Khubilai Khan, 115–116.

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China (November 15, 2000). "Did Tibet Become an Independent Country after the Revolution of 1911?". Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ↑ a b Information Office of the State Council, Testimony of History, 75.

- ↑ a b c Chen, Tibetan History, 48.

- ↑ Powers 2004, pp. 58-9

- ↑ Hans Bielenstein, The Bureaucracy of Han Times (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 110.

- ↑ a b c Wang & Nyima, The Historical Status of China's Tibet, 42. Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «wang nyima 42» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ a b c d Georges Dreyfus, "Cherished memories, cherished communities: proto-nationalism in Tibet", in The History of Tibet: Volume 2, The Medieval Period: c. AD 850–1895, the Development of Buddhist Paramountcy (New York: Routledge, 2003), 504.

- ↑ a b Chen, Tibetan History, 44.

- ↑ a b c d e Wylie, "Lama Tribute in the Ming Dynasty", 469–470.

- ↑ Wang & Nyima, The Historical Status of China's Tibet, 35.

- ↑ a b c d Chen Qingying, Tibetan History (Beijing: China Intercontinental Press, 2003), 51; original text: 余非不知此是大地之大主宰為佛法著想之諭旨,亦非不遵不敬陛下之詔書,但我每與眾人相會,便發生重病,故不能遵照聖旨而行,惟祈陛下如虛空廣大之胸懷,不致不悅,實為幸甚。 Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «chen 51» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ a b A. Tom Grunfeld, The Making of Modern Tibet (New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1996), 40.

- ↑ a b c d e f Rossabi, "The Ming and Inner Asia," 244.

- ↑ a b c d e Dawa Norbu, China's Tibet Policy (Richmond: Curzon, 2001), 58.

- ↑ a b Laird, «The Story of Tibet», 137.

- ↑ Yiu Yung-chin, "Two Focuses of the Tibet Issue", in Tibet Through Dissident Chinese Eyes: Essays on Self-determination (New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1998), 121.

- ↑ Shih-Shan Henry Tsai, Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), 187–188.

- ↑ a b c d e Chan, "The Chien-wen, Yung-lo, Hung-shi, and Hsuan-te reigns", 263.

- ↑ Wylie, "Lama Tribute in the Ming Dynasty", 470–471.

- ↑ Riggs, "Tibet in Extremis", Far Eastern Survey 19, no. 21 (1950): 226.

- ↑ Wylie, "Lama Tribute in the Ming Dynasty", 468–469.

- ↑ Goldstein, The Snow Lion and the Dragon, 5.

- ↑ a b Kolmas, Tibet and Imperial China, 29.

- ↑ a b c d e The Ming Biographical History Project of the Association for Asian Studies, Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644: 明代名人傳: Volume 1, A-L (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976), 482.

- ↑ a b c Karma Thinley, The History of the Sixteen Karmapas of Tibet (Boulder: Prajna Press, 1980), 72. Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «thinley 72» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ a b c Tsai, Perpetual Happiness, 84.

- ↑ a b c Tsai, Perpetual Happiness, 187.

- ↑ Norbu, China's Tibet Policy, 51–52.

- ↑ Rossabi, Khubilai Khan, 41.

- ↑ Powers 2004, pg. 53

- ↑ a b c d e Chen Qingying, Tibetan History (China Intercontinental Press, 2003), 52. Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; el nombre «chen 52» está definido varias veces con contenidos diferentes - ↑ Sperling, "The 5th Karma-pa and some aspects of the relationship between Tibet and the Early Ming", 477.

- ↑ Thinley, The History of the Sixteen Karmapas of Tibet, 74.

- ↑ Marsha Weidner, "Imperial Engagements with Buddhist Art and Architecture: Ming Variations of an Old Theme", in Cultural Intersections in Later Chinese Buddhism (Manoa: University of Hawaii Press, 2001), 121.

- ↑ a b c d Norbu, China's Tibet Policy, 52.

- ↑ a b Kolmas, Tibet and Imperial China, 32.

- ↑ a b c Information Office of the State Council, Testimony of History, 95.

- ↑ a b John E. Vollmer, Silk for Thrones and Altars: Chinese Costumes and Textiles from the Liao through the Qing Dynasty (Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2004), 98–100.

- ↑ Wang & Nyima, The Historical Status of China's Tibet, 39.

- ↑ Sperling, "The 5th Karma-pa and some aspects of the relationship between Tibet and the Early Ming", 474–475.