Aminas traza

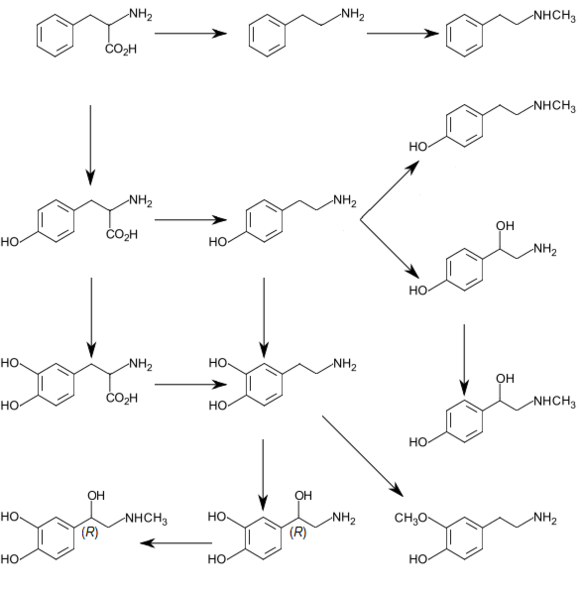

Las aminas traza son un grupo de compuestos endógenos que actúan como agonistas del receptor TAAR1[1] – y por lo tanto, como neuromoduladores monoaminérgicos.[2][3][4] – se encuentran metabólica y estructuralmente relacionados con los neurotransmisores monoaminas clásicos.[5] Sin embargo, comparados con las monoaminas clásicas, se encuentran en concentraciones traza.[5] Se encuentran heterogéneamente distribuidos en el cerebro de los mamíferos y en los tejidos nerviosos periféricos, tanto en unos como en otros exhiben una alta tasa metabólica.[5][6] Aunque pueden sintetizarse dentro de los sistemas principales de síntesis de los neurotransmisores monoamina,[7] existe evidencia que sugiere que algunos de estos compuestos podrían participar en su propios sistemas neurotransmisores independientes.[2]

Las aminas traza desempeñan importantes papeles en la regulación de los neurotransmisores monoamina en la hendidura sináptica de las neuronas monoaminérgicas que poseen el receptor TAAR1.[6] Poseen efectos presinápticos bien documentados simimilares a las de las anfetaminas en las neuronas monoaminérgicas por medio de la activación del receptor TAAR1;[3][4] específicamente, la activación del TAAR1 en las neuronas promueve la liberación[nota 1] y previene la recaptación de los neurotransmisores monoamina desde la hendidura sináptica, mientras que inhibien el disparo neuronal.[6][8] La fenetilamina y la anfetamina poseen farmacodinámicas similares en las neuronas dopaminérgicas humanas, ya que ambos compuestos inducen el eflujo desde el transportador vesicular de monoaminas tipo 2 (VMAT2)[7][9] y activan al TAAR1 con una efectividad comparable.[6]

Al igual de lo que ocurre con la dopamina, noradrenalina y serotonina, las aminas traza se encuentran implicadas en un amplio grupo de trastornos afectivos y cognitivos humanos, tales como el ADHD,[3][4][10] depresión[3][4] y esquizofrenia,[2][3][4] entre otros.[3][4][10] La hipofunción del sistema aminérgico traza es particularmente relevante para el ADHD, ya que la concentración de fenetilamina urinaria y sanguínea son significativamente menores en los individuos con ADHD en comparación con individuos control y los dos medicamentos más comúnmente prescriptos para el ADHD son la anfetamina y el metilfenidato, aumentan la biosíntesis de fenetilamina en aquellos individuos con ADHD que responden al tratamiento.[3][11][12] Una revisión sistemática de los biomarcadores para ADHD indica además que los niveles urinarios de fenetilamina podrían ser un buen marcador diagnóstico para la ADHD.[3][11][12]

Listado de aminas traza[editar]

Entre las aminas traza humanas se incluyen:

- Fenetilaminas (relacionadas con las catecolaminas):

- Fenetilamina[5][6][16] (PEA)

- N-Metilfenetilamina[4][5][16] (isómero endógeno de la anfetamina)

- Feniletanolamina[17][16]

- m-Tiramina[5][16]

- p-Tiramina[5][16]

- 3-Metoxitiramina[4][16]

- N-Metiltiramina[4][5][16]

- m-Octopamina[5][16]

- p-Octopamina[5][16]

- Sinefrina[4][16]

- Tironamina y compuestos relacionados:

- Triptamina[4][6][16]

Aunque no se trata de aminas traza por sí mismas, las monoaminas clásicas noradrenalina, serotonina, e histamina son agonistas parciales del receptor humano TAAR1;[6] la dopamina es un agonista de muy alta afinidad sobre el receptor TAAR1 humano.[8][18][19] N-Metiltriptamina y N,N-dimetiltriptamina son aminas endógenas en humanos, sin embargo, hasta el año 2015 no se ha detectado que puedan unirse al receptor TAAR1.[2]

Véase también[editar]

Notas[editar]

- ↑ Ciertas aminas traza (tal como por ejemplo la fenetilamina) inhiben funcionalmente al transportador vesicular de monoaminas VMAT2, mientras que otros, no lo hacen (por ejemplo, la octopamina). Las aminas traza que no inhiben la función VMAT2 en neuronas monoaminérgicas, no son capaces de liberar neurotransmisores tan efectivamente com lo hacen las que si.

Referencias[editar]

- ↑ Panas MW, Xie Z, Panas HN, Hoener MC, Vallender EJ, Miller GM (December 2012). «Trace amine associated receptor 1 signaling in activated lymphocytes». J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 7 (4): 866-76. PMC 3593117. PMID 22038157. doi:10.1007/s11481-011-9321-4. «Trace Amine Associated Receptor 1 (TAAR1) is a G protein coupled receptor (GPCR) that responds to a wide spectrum of agonists, including endogenous trace amines, ...»

- ↑ a b c d Burchett SA, Hicks TP (August 2006). «The mysterious trace amines: protean neuromodulators of synaptic transmission in mammalian brain». Prog. Neurobiol. 79 (5–6): 223-46. PMID 16962229. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.07.003.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Berry MD (January 2007). «The potential of trace amines and their receptors for treating neurological and psychiatric diseases». Rev Recent Clin Trials 2 (1): 3-19. PMID 18473983. doi:10.2174/157488707779318107. «changes in trace amines, in particular PE, have been identified as a possible factor for the onset of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [5, 27, 43, 78]. PE has been shown to induce hyperactivity and aggression, two of the cardinal clinical features of ADHD, in experimental animals [100]. Hyperactivity is also a symptom of phenylketonuria, which as discussed above is associated with a markedly elevated PE turnover [44]. Further, amphetamines, which have clinical utility in ADHD, are good ligands at trace amine receptors [2]. Of possible relevance in this aspect is modafanil, which has shown beneficial effects in ADHD patients [101] and has been reported to enhance the activity of PE at TAAR1 [102]. Conversely, methylphenidate, which is also clinically useful in ADHD, showed poor efficacy at the TAAR1 receptor [2]. In this respect it is worth noting that the enhancement of functioning at TAAR1 seen with modafanil was not a result of a direct interaction with TAAR1 [102].

More direct evidence has been obtained recently for a role of trace amines in ADHD. Urinary PE levels have been reported to be decreased in ADHD patients in comparison to both controls and patients with autism [103-105]. Evidence for a decrease in PE levels in the brain of ADHD patients has also recently been reported [4]. In addition, decreases in the urine and plasma levels of the PE metabolite phenylacetic acid and the precursors phenylalanine and tyrosine have been reported along with decreases in plasma tyramine [103]. Following treatment with methylphenidate, patients who responded positively showed a normalization of urinary PE, whilst non-responders showed no change from baseline values [105].» - ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). «A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family». Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (5): 274-281. PMID 15860375. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. «In addition to the main metabolic pathway, TAs can also be converted by nonspecific N-methyltransferase (NMT) [22] and phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) [23] to the corresponding secondary amines (e.g. synephrine [14], N-methylphenylethylamine and N-methyltyramine [15]), which display similar activities on TAAR1 (TA1) as their primary amine precursors...Both dopamine and 3-methoxytyramine, which do not undergo further N-methylation, are partial agonists of TAAR1 (TA1). ...

The dysregulation of TA levels has been linked to several diseases, which highlights the corresponding members of the TAAR family as potential targets for drug development. In this article, we focus on the relevance of TAs and their receptors to nervous system-related disorders, namely schizophrenia and depression; however, TAs have also been linked to other diseases such as migraine, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, substance abuse and eating disorders [7,8,36]. Clinical studies report increased β-PEA plasma levels in patients suffering from acute schizophrenia [37] and elevated urinary excretion of β-PEA in paranoid schizophrenics [38], which supports a role of TAs in schizophrenia. As a result of these studies, β-PEA has been referred to as the body’s ‘endogenous amphetamine’ [39]». - ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Broadley KJ (March 2010). «The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines». Pharmacol. Ther. 125 (3): 363-375. PMID 19948186. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. «Trace amines are metabolized in the mammalian body via monoamine oxidase (MAO; EC 1.4.3.4) (Berry, 2004) (Fig. 2) ... It deaminates primary and secondary amines that are free in the neuronal cytoplasm but not those bound in storage vesicles of the sympathetic neurone ... Similarly, β-PEA would not be deaminated in the gut as it is a selective substrate for MAO-B which is not found in the gut ...

Brain levels of endogenous trace amines are several hundred-fold below those for the classical neurotransmitters noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin but their rates of synthesis are equivalent to those of noradrenaline and dopamine and they have a very rapid turnover rate (Berry, 2004). Endogenous extracellular tissue levels of trace amines measured in the brain are in the low nanomolar range. These low concentrations arise because of their very short half-life ...» - ↑ a b c d e f g h Miller GM (January 2011). «The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity». J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164-176. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x.

- ↑ a b Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). «VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse». Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216: 86-98. PMC 4183197. PMID 21272013. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. «[Trace aminergic] neurons in mammalian CNS would be identifiable as neurons expressing VMAT2 for storage, and the biosynthetic enzyme aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC).»

- ↑ a b Grandy DK, Miller GM, Li JX (February 2016). «"TAARgeting Addiction"-The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution: An Overview of the Plenary Symposium of the 2015 Behavior, Biology and Chemistry Conference». Drug Alcohol Depend. 159: 9-16. PMC 4724540. PMID 26644139. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.014. «TAAR1 is a high-affinity receptor for METH/AMPH and DA».

- ↑ Offermanns, S; Rosenthal, W, eds. (2008). Encyclopedia of Molecular Pharmacology (2nd edición). Berlin: Springer. pp. 1219–1222. ISBN 3540389164.

- ↑ a b Sotnikova TD, Caron MG, Gainetdinov RR (August 2009). «Trace amine-associated receptors as emerging therapeutic targets». Mol. Pharmacol. 76 (2): 229-35. PMC 2713119. PMID 19389919. doi:10.1124/mol.109.055970. «Although the functional role of trace amines in mammals remains largely enigmatic, it has been noted that trace amine levels can be altered in various human disorders, including schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Tourette syndrome, and phenylketonuria (Boulton, 1980; Sandler et al., 1980). It was generally held that trace amines affect the monoamine system indirectly via interaction with plasma membrane transporters [such as plasma membrane dopamine transporter (DAT)] and vesicular storage (Premont et al., 2001; Branchek and Blackburn, 2003; Berry, 2004; Sotnikova et al., 2004). ...

Furthermore, DAT-deficient mice provide a model to investigate the inhibitory actions of amphetamines on hyperactivity, the feature of amphetamines believed to be important for their therapeutic action in ADHD (Gainetdinov et al., 1999; Gainetdinov and Caron, 2003). It should be noted also that the best-established agonist of TAAR1, β-PEA, shared the ability of amphetamine to induce inhibition of dopamine-dependent hyperactivity of DAT-KO mice (Gainetdinov et al., 1999; Sotnikova et al., 2004).

Furthermore, if TAAR1 could be proven as a mediator of some of amphetamine's actions in vivo, the development of novel TAAR1-selective agonists and antagonists could provide a new approach for the treatment of amphetamine-related conditions such as addiction and/or disorders in which amphetamine is used therapeutically. In particular, because amphetamine has remained the most effective pharmacological treatment in ADHD for many years, a potential role of TAAR1 in the mechanism of the “paradoxical” effectiveness of amphetamine in this disorder should be explored.» - ↑ a b Irsfeld M, Spadafore M, Prüß BM (September 2013). «β-phenylethylamine, a small molecule with a large impact». Webmedcentral 4 (9). PMC 3904499. PMID 24482732. «While diagnosis of ADHD is usually done by analysis of the symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), PEA was recently described as a biomarker for ADHD (Scassellati et al., 2012). This novel discovery will improve the confidence of the diagnostic efforts, possibly leading to reduced misdiagnosis and overmedication. Specifically, the urinary output of PEA was lower in a population of children suffering from ADHD, as compared to the healthy control population, an observation that was paralleled by reduced PEA levels in ADHD individuals (Baker et al., 1991; Kusaga, 2002). In a consecutive study (Kusaga et al., 2002), those of the children suffering with ADHD were treated with methylphenidate, also known as Ritalin. Patients whose symptoms improved in response to treatment with methylphenidate had a significantly higher PEA level than patients who did not experience such an improvement in their condition (Kusaga et al., 2002).»

- ↑ a b Scassellati C, Bonvicini C, Faraone SV, Gennarelli M (October 2012). «Biomarkers and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analyses». J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 51 (10): 1003-1019.e20. PMID 23021477. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.015. «Although we did not find a sufficient number of studies suitable for a meta-analysis of PEA and ADHD, three studies20,57,58 confirmed that urinary levels of PEA were significantly lower in patients with ADHD compared with controls. ... Administration of D-amphetamine and methylphenidate resulted in a markedly increased urinary excretion of PEA,20,60 suggesting that ADHD treatments normalize PEA levels. ... Similarly, urinary biogenic trace amine PEA levels could be a biomarker for the diagnosis of ADHD,20,57,58 for treatment efficacy,20,60 and associated with symptoms of inattentivenesss.59 ... With regard to zinc supplementation, a placebo controlled trial reported that doses up to 30 mg/day of zinc were safe for at least 8 weeks, but the clinical effect was equivocal except for the finding of a 37% reduction in amphetamine optimal dose with 30 mg per day of zinc.110».

- ↑ Broadley KJ (March 2010). «The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines». Pharmacol. Ther. 125 (3): 363-375. PMID 19948186. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005.

- ↑ Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). «A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family». Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (5): 274-281. PMID 15860375. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007.

- ↑ Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). «The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D». Eur. J. Pharmacol. 724: 211-218. PMID 24374199. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Khan MZ, Nawaz W (October 2016). «The emerging roles of human trace amines and human trace amine-associated receptors (hTAARs) in central nervous system». Biomed. Pharmacother. 83: 439-449. PMID 27424325. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.002.

- ↑ Wainscott DB, Little SP, Yin T, Tu Y, Rocco VP, He JX, Nelson DL (January 2007). «Pharmacologic characterization of the cloned human trace amine-associated receptor1 (TAAR1) and evidence for species differences with the rat TAAR1». The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 320 (1): 475-85. PMID 17038507. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.112532.

- ↑ Maguire JJ, Davenport AP (19 de julio de 2016). «Trace amine receptor: TA1 receptor». IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Consultado el 22 de septiembre de 2016. «Rank order of potency

tyramine > β-phenylethylamine > octopamine = dopamine». - ↑ «Dopamine: Biological activity». IUPHAR/BPS guide to pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Consultado el 29 de enero de 2016.