Usuario:Dgff/Taller

Rodrigo Martínez (en latín: Rudericus Martini) (murió en julio de 1138) fue noble leonés, terrateniente, cortesano, líder militar, gobernador y diplomado, "la figura más poderosa de la región oeste de Tierra de Campos," quien "emerge como el más regular visitante de la corte de Alfonso VII entre 1127 y 1138."[1] Era miembro de la familia Flagínez, quienes subieron al rango más alto en el reino y conocieron su final en el campo de batalla.

Era el hijo mayor de Martín Flaínez y Sancha Fernández. A lo largo de toda su vida estuvo muy unido a sus hermanos Pedro yOsorio Martínez. Los tres hermanos Martínez murieron en el campo de batalla.[2] De Martín Flaínez se sabe que donó un campo, dinero y velas al monasterio de Santa Eugenia de Cordovilla ya que los monjes le hicieron un exorcismo al joven Rodrigo, con éxito.[3]

De parte de la Corona: gobernador y diplomado[editar]

El primer hecho de la carrera pública de Rodrigo data del 1 de Mayo de 1110.[4] En 1117 gobernaba la tenencia de Castroverde. Entre 1117 y 1136 gobernó la tenencia de Becilla de Valderaduey.[4] De 1125 a 1137 lo hizo con la de Aguilar de Campoo. La Reina Urraca murió el 8 de Marzo de 1126. Cuando Alfonso VII tomó finalmente el control de las "torres de León", la fortaleza que custodiaba la capital imperial de León, y Rodrigo con otros nobles leoneses fue a rendirle homenaje.[5] En 1134 gobernó Mayorga y en 1135 las de Atienza y Medina del Campo al mismo tiempo. En 1137 tuvo la de Calahorra, y hay una referencia errónea en una carta de la época que lo indica en 1140.[4] En 1136–37 también gobernó la Tierra de Campos. Incluso parece ser que quizá, en algunos puntos, gobernó Grajal de Campos, hasta que una carta de 1152 refiere que los dos, él yRamiro Fróilaz tenían el título de apoderados de Grajal.[4] Entre 1126 y 1138 gobernó las torres de León para la corona. Desde 1120 a 1126 he tuvo la tenencia de Melgar de Arriba (o posiblemente Melgar de Fernamental).[4] Es posible que en 1126 tuviera brevemente la de Somoza, pero la única carta que lo refiere no es muy fiable. Desde 1123 a 1136 gobernó Villalobos. Desde 1132 hasta su muerte gobernó Zamora.[6]

Hacia el final de 1128 Rodrigo había conseguido llegar a conde.[4] En 1129 contrató a Pedro Manga como su mayordomo. Pedro luego tendría las tenencias de Luna y Valencia de Don Juan de la corona.[4] En 1131 un tal Fernando Menéndez actuó como el párraco de Rodrigo en Zamora.[7]

En 1133 Rodrigo Martínez y Gutierrez Fernández guiaron una embajada hasta Rueda de Jalón (Rota) para negociar con el insignificante príncipe musulmán Sayf al-Dawla (Zafadola). Los "recibieron honorablemente [y fueron presentados] con unos maravillosos presentes."[8] Acompañaron a Sayf de vuelta a León para visitar a Alfonso VII. Rodrigo obtuvo una gran recompensa del monarca por su lealtad en Junio-Julio de 1135 que consistio en algunas tierras confiscadas al fracasado revolucionario asturiano Gonzalo Peláez.[4] Entre 1135 y 1137 Rodrigo adquirió tierras en Castrillo.[4]

Private transactions: marriage and property[editar]

On 7 October 1123 he made a donation to the Benedictine monastery at Sahagún.[4] On 1 July 1131 Rodrigo donated an estate at Oteruelo to Gonzalo Alfonso and Teresa Peláez.[4] Between 1130 and 1132 he had a dispute with Arias II, Bishop of León, over the property owned by one Pedro Peláez.[9] On 29 March 1133 Alfonso VII granted immunity (Latin cautum, Spanish coto) to the count's estate at Castellanos. This gave Rodrigo the right to collect taxes and the profits of justice, to call upon the male denizens for military service, and to refuse entry to royal officials such as the merino and sayón.[10]

Rodrigo married Urraca Fernández, daughter of Fernando Garcés de Hita and Estefanía Armengol. The couple was betrothed while she was no more than ten years old, at which time (21 November 1129) Rodrigo granted her a bridewealth consisting in eleven villages in the Campos Góticos.[11] The charter, carta de arras, noting this gift is in the archives of Valladolid. In it Rodrigo refers to Urraca as Fernandi Garcie et infantisse domine Stephanie filie, "daughter of Fernando Garcés and the infantissa Doña Estefanía," a bragging declaration, since the title infantissa implied that Estefanía was of royal lineage, although she was in fact a daughter of Count Ermengol V of Urgell. It has been speculated that she bore the title because of her marriage to Fernando, who may have been a natural son of García II of Galicia.[12]

Urraca never bore him any children of whom we have record, but the couple were active in property acquisitions. Together they acquired properties scattered throughout the Campos from Carrión in the east to León in the west to Zamora in the south (de Carrione usque in Legionem et Cemorem et per totos Campos).[13] These acquisitions (gananciales) were bought by Alfonso VII after Rodrigo's death. On 21 January 1139 the emperor granted Amusco and an estate at Vertavillo to Urraca in exchange for Manganeses and "all those purchases and gains, which she made with her husband Rodrigo Martínez" (totis illis comparationibus et gananzes, quas fecit cum marito suo Roderico Martinez).[14] At some point after Rodrigo's death Urraca began an affair with Alfonso VII, eventually giving birth to a daughter by him, Estefanía, who married Fernando Rodríguez de Castro.[15] Alfonso's purchase of her and Rodrigo's gananciales may have been designed to provide for this daughter. Urraca conducted a number of property transactions with Alfonso between 1139 and 1148.[16]

Military activities and death[editar]

During the rebellion of 1130 led by the González de Lara brothers, Pedro and Rodrigo, and their kinsman Bertrán de Risnel, Alfonso VII called upon Rodrigo and Osorio Martínez to attack Pedro Díaz, a supporter of the rebels, in his castle at Valle. According to the Chronica Adefonsi, Rodrigo and Osorio surrounded the castle and sent reports to Alfonso about the insults the garrison was hurling at them because of their failed assaults. The king came and the castle was taken and razed.[17] Reportedly Pedro Díaz, upon surrendering, said to Alfonso, "My Lord and King, I stand at fault; I earnestly beg you, for the love of God who always aids you, do not hand me or my family over to Count Rodrigo. Instead, you yourself take vengeance upon me as you see fit."[17] Rodrigo's reputation for ill treatment of his prisoners is also recorded in the Chronica:

Count Rodrigo captured other knights. He sent some of these to prison until they surrendered all their possessions to him. He made others serve him for several days without any compensation. Those who had been insulting him he yoked with oxen to plow and feed on grass like cattle. He also made them eat straw from a manger. After he had stripped them of all their riches, he allowed the pathetic prisoners to go their way.[18]

On the orders of its rebel leader, Gimeno Íñiguez, the town of Coyanza also surrendered to the king to avoid falling into Rodrigo's hands.[18]

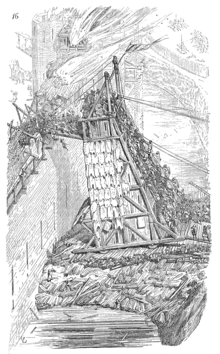

Rodrigo died at the Siege of Coria, where he was assisting the emperor with his own knightly retinue (mesnada), in July 1138. The siege was the culmination of a summer razzia deep into al-Andalus. The razzia had begun in May under the command of Alfonso, Rodrigo Martínez, and Rodrigo Fernández de Castro.[19] Rodrigo Martínez died during an assault on the city walls, described in the Chronica Adefonsi:

The Emperor summoned the commanders and ordered them to mobilize the war engines in preparation for the assault on the city. He left with his hunters for the mountains then in search of deer, boar and bear. In the morning the assault was begun. Consul Rodrigo Martínez himself climbed one of the wooden towers. Many knights, archers and slingers went up the tower with him. Then one of the enemy by pure chance shot an arrow at the tower which the consul had climbed. Because of our sins, the arrow hit its target on the other side of the wickerwork. The iron point of the arrow struck the neck of the Consul. It pierced his headpiece and corselet and wounded him. Nevertheless, after the Consul realized that he was wounded, he quickly grasped the point of the arrow and, removed it. At once he began to hemorrhage. Neither the conjurers nor the physicians could stop the bleeding. Finally Rodrigo said to those around him, "Take off my arms, for I am extremely disheartened." Immediately they removed his arms and carried him to his tent. Throughout the entire day they attempted to cure his wound. Around sunset all hope in medicine was lost, and he died. As soon as the news had spread through the camp, there was tremendous mourning—more than anyone had imagined. Upon returning from the mountains, the Emperor was informed of the Consul's death. He learned the cause upon entering the camp. Alfonso gathered all of his advisors, and in their presence, he appointed Osorio, Rodrigo's brother, to be consul in his place.[20]

The siege was lifted the next day, and Rodrigo's body was immediately conducted to its burial place in León by his brother Osorio "accompanied by his own military force and by that of his brother".[21] Rodrigo was buried in the family mausoleum beside his parents, in a church next to the Cathedral of Santa María, possibly the monastery of San Pedro de los Huertos, which his parents had received by a royal grant of Urraca of Zamora and Elvira of Toro in 1099.[22] Osorio succeeded Rodrigo as count and received his tenencias of Aguilar, the Campos, León, and Zamora.[23]

Notes[editar]

- ↑ Barton (1997), 129.

- ↑ Barton (1997), 57.

- ↑ Barton (1997), 209.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Barton (1997), 294–95.

- ↑ CAI, I, §4.

- ↑ Barton (1997), 117 n87.

- ↑ Reilly (1998), 194.

- ↑ CAI, I, §28; Barton, 140.

- ↑ Cf. Fletcher (1978), 238–39, doc. VIII in the Appendix.

- ↑ Barton (1997), 92.

- ↑ Barton (1997), 52–53. Estefanía was Fernando's second wife, and he granted her her bridewealth in November 1119, cf. Barton, 40.

- ↑ Canal Sánchez-Pagín (1984), 39, 52–53, suggests that Fernando avoided the title infante because his father had been dethroned and died in prison. Queen Urraca on two occasions referred to Estefanía as her congermana, cousin.

- ↑ Barton (1997), 71 and 118 n90.

- ↑ Barton (1997), 118 and n90.

- ↑ Canal Sánchez-Pagín (1984), 54.

- ↑ She received imperial grants of land on 9 September 1140 and on 3 February 1148, cf. Barton 118 n90.

- ↑ a b CAI, I, §§19–20.

- ↑ a b CAI, I, §21.

- ↑ Barton (1997), 167–68. The raiding army was known as an algara. It included, in this case, the palace guard and the militia of Salamanca. For this campaign see CAI, II, §§135–36.

- ↑ CAI, II, §§137–38.

- ↑ CAI, II, §139.

- ↑ Barton (1997), 45–46. For his burial see CAI, II, §139: "The mourning over the death of Rodrigo Martínez increased in every city. In León they buried him with honors in his father's tomb near the Basilica of Saint Mary. The tomb is located very near the episcopal throne."

- ↑ Barton (1997), 117.

Bibliography[editar]

- S. Barton. 1997. The Aristocracy in Twelfth-century León and Castile. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- S. Barton. 2000. "From Tyrants to Soldiers of Christ: The Nobility of Twelfth-century León-Castile and the Struggle Against Islam". Nottingham Medieval Studies, 44, 28–48.

- J. M. Canal Sánchez-Pagín. 1986. "El conde leonés Fruela Díaz y su esposa la navarra doña Estefanía Sánchez (siglos XI–XII)", Príncipe de Viana, 47:177, 23–42.

- R. A. Fletcher. 1978. The Episcopate in the Kingdom of León in the Twelfth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- R. A. Fletcher. 1984. Saint James's Catapult: The Life and Times of Diego Gelmírez of Santiago de Compostela. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- G. E. Lipskey. 1972. The Chronicle of Alfonso the Emperor: A Translation of the Chronica Adefonsi imperatoris. PhD thesis, Northwestern University. [Cited as CAI.]

- P. Martínez Sopena. 1985. La Tierra de Campos Occidental: poblamiento, poder y comunidad del siglo X al XIII. Valladolid.

- P. Martínez Sopena. 1990. "El conde Rodrigo de León y los suyos: herencia y expectativa del poder entre los siglos X y XII." R. Pastor ed., Relaciones de poder, de produccion y parentesco en la Edad Media y Moderna. Madrid, pp. 5–84.

- B. F. Reilly. 1982. The Kingdom of León-Castilla under Queen Urraca, 1109–1126. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- B. F. Reilly. 1998. The Kingdom of León-Castilla under King Alfonso VII, 1126–1157. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.