Diferencia entre revisiones de «Ofensiva de Gorlice-Tarnów»

Traducción inconclusaundefinedEn desarrollo |

(Sin diferencias)

|

Revisión del 13:08 8 jul 2014

| Ofensiva de Gorlice-Tarnów | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Primera Guerra Mundial Parte de Frente oriental y Primera Guerra Mundial | ||||

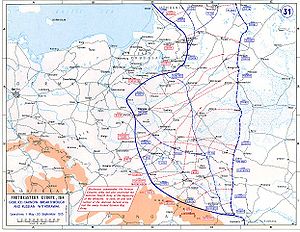

Ofensiva de Gorlice-Tarnów y retirada rusa. | ||||

| Fecha | 2 de mayo - 22 de junio, 1915 | |||

| Lugar | Zona de Gorlice y Tarnów, al sudeste de Cracovia | |||

| Coordenadas | 49°39′16″N 21°09′33″E / 49.6544444444, 21.1591666667 | |||

| Resultado | Victoria de los Imperios Centrales. | |||

| Consecuencias | Colapso total de las líneas rusas y retirada al interior de Rusia. | |||

| Beligerantes | ||||

|

| ||||

| Comandantes | ||||

|

| ||||

| Unidades militares | ||||

| ||||

| Bajas | ||||

| ||||

La Ofensiva de Gorlice–Tarnów tuvo lugar en 1915, durante la Primera Guerra Mundial. Comenzó como una ofensiva menor germana para aliviar la presión rusa sobre Austria-Hungría en el Frente Oriental, pero resultó en el colapso absoluto de las líneas rusas y su retirada al interior de Rusia. Siguieron a la ofensiva una serie de acciones que duraron hasta que llegó el mal tiempo, bien entrado octubre.

Trasfondo

En las campañas iniciales en el Frente Oriental, el VIII Ejército alemán había conducido una serie de acciones casi milagrosas contra los dos ejércitos rusos que se le enfrentaban. Tras rodear y destruir el II Ejército Ruso en la batalla de Tannenberg, a finales de agosto, Paul von Hindenburg y Erich Ludendorff avanzaron sus tropas para enfrentarse al I Ejército Ruso en la primera batalla de los Lagos Masurianos, destruyéndolo prácticamente por completo en la persecución.

Cuando pararon las acciones a finales de septiembre, la práctica mayoría de los dos ejércitos rusos había quedado destruida, y todas las fuerzas rusas habían sido expulsadas de los Lagos Masurianos, al nordeste de la actual Polonia, con unas bajas que ascendían a 200.000 hombres.

Más al sur, sin embargo, el grueso de las fuerzas rusas se enfrentaban a un número equivalente de tropas austrohúngaras, que comenzaron su propia ofensiva a finales de agosto, e inicialmente empujaron a los rusos de vuelta a lo que hoy es la Polonia central. No obstante, un contraataque ruso bien ejecutado a finales de septiembre les rechazó hacia la frontera en desorden, permitiendo a los rusos comenzar el sitio de Przemyśl.

The Germans came to their aid by forming up the 9th Army and attacking during the Battle of the Vistula River. Although it was initially successful, the attack eventually petered out and the Germans returned to their starting points.

The Russians followed up by redeploying their armies for a further offensive into Silesia, placing both Austria and Germany at risk. When the Central Powers heard of this, the 9th Army was redeployed to the north, allowing them to put serious pressure on the Russian right flank in what developed as the Battle of Łódź in early November. The Germans failed to encircle the Russian units, and the battle ended inconclusively with an orderly Russian withdrawal to the east near Warsaw. Weather prevented further actions over the next months.

Combates

General Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, the Chief of Staff of the Austro-Hungarian Army, originally proposed the idea of breaking up the front line in the area of Gorlice. At first this idea was rejected by German Chief of Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, who believed that the fate of the war depended on the western front. Later he changed his mind and decided for a major offensive in the Gorlice-Tarnów area, south-east of Krakow, at the far southern end of the Eastern Front.

In April 1915, the recently formed German 11th Army (10 infantry divisions under General August von Mackensen) was transferred from the Western Front. Along with the Austro-Hungarian IV Army (eight infantry and one cavalry divisions under Archduke Joseph Ferdinand), it had to cope with the Russian III Army (18½ infantry and five and a half cavalry divisions, under General D.R. Radko-Dmitriev), which held that sector.

General Mackensen had been given command of both German and Austro-Hungarian forces, and on 2 May, after a heavy artillery bombardment, he launched an attack which caught the Russians by surprise. He concentrated 10 infantry and one cavalry division (126,000 men, 457 light, 159 heavy pieces of artillery and 96 mortars) on the 35 km (21,7 mi) of the breakthrough sector of the front line against five Russian divisions (60,000 men with 141 light and four heavy pieces of artillery).

Opposing forces

Central Powers (arrayed north to south):

Austro-Hungarian IV Army (Austro-Hungarian units unless otherwise indicated): Combined Division “Stöger-Steiner”; XIV Corps (German 47th Reserve Division, Group Morgenstern, 8th & 3rd Infantry Divisions); IX corps (106th Landsturm & 10th Infantry Divisions); In reserve behind IX Corps: 31st Infantry Brigade (“Szende Brigade”), 11th Honved Cavalry Division.

German 11th Army (German units unless otherwise indicated): Guard Corps (1st & 2d Guard Divisions); Austro-Hungarian VI Corps (39th Honved Infantry & 12th Infantry Divisions); XXXXI Reserve Corps (81st & 82nd Reserve Divisions); Combined Corps “Kneussl” (119th and Bavarian 11th Infantry Divisions); In reserve: X Corps (19th & 20th Infantry Divisions).

Austro-Hungarian III Army, X Corps (21st Landsturm, 45th Landsturm, 2nd Infantry & 24th Infantry Divisions)

Russian 3rd Army (north to south):

IX Corps (3 militia brigades, 3 regiments of 5th Infantry Division, 2 militia brigades, 3 regiments of 42nd Infantry Division, 70th Reserve Division, 7th Cavalry Division [in reserve]); X Corps (31st Infantry & 61st Reserve Divisions, 3 regiments of 9th Infantry Division); XXIV Corps (3 regiments of 49th Infantry Division, 48th Infantry Division & 176th (Perevolochensk) Infantry Regiment of 44th Infantry Division); XII Corps (12th Siberian Rifle Division, 12th & 19th Infantry Divisions & 17th (Chernigov) Hussar Regiment); XXI Corps (3 regiments of 33rd Infantry Division & 173rd (Kamenets) Regiment of 44th Infantry Division); XXIX Corps (Brigade of 81st Infantry Division, 3rd Rifle Brigade, 175th (Batursk) Infantry Regiment of 44th Infantry Division & 132nd (Bender) Infantry Regiment of 33rd Infantry Division); 11th Cavalry Division. Behind the Russian front lines: Scattered across the rear of 3rd Army: 3rd Caucausus Cossack Division, 19th (Kostroma) Infantry Regiment of 5th Infantry Division, 33rd (Elets) Infantry Regiment of 9th Infantry Division; 167th (Ostroisk) Infantry Regiment of 42nd Infantry Division; Army Reserve: Brigade of 81st Infantry Division, 3 regiments of 63rd Reserve Division, Composite Cavalry Corps (16th Cavalry Division (less 17th Hussar Regiment), 2nd Consolidated Cossack Division); 3rd Don Cossack Division

Developments

The Central Powers shattered the Russian defenses, and the Russian lines collapsed. Radko-Dimitrejew quickly sent two divisions against the Austro-German breakthrough, but being ill-prepared they were utterly annihilated without being able to report back to their headquarters. From Russian point of view, both divisions simply disappeared from the map.

The Russian III Army left in enemy hands about 140,000 prisoners, and almost ceased to exist as a fighting unit. The 3rd Caucasian Corps, for example, brought up to establishment of 40,000 men in April, found itself reduced to 8,000. It was thrown into the battle on the San against the Austrian I Army, and succeeded in taking some 6,000 prisoners and nine guns. One division was down to 900 men on 19 May.

The Russians were forced to withdraw, the Central Powers recaptured most of Galicia, and the Russian threat to Austria-Hungary was averted. Particularly gratifying was the recapture of Przemyśl on 3 June. The same day, fresh offensives were launched: the Austrian IV and VII armies on the flank of the XI Army aiming for the River Dniester.

By 17 June, the defenders had pulled back on Lwów (later Lvov),(now Lviv) the capital of Galicia, and on the 22nd Austria-Hungary's fourth largest city was recaptured. With this loss, which meant that most of Galicia had returned to Austrian hands, the lines stabilized in the south. The penetration progressed about 160 km (99,4 mi) at its deepest, reducing the Polish salient to perhaps ⅓ of its pre-war size.

Consecuencias

Trying to save Russian forces from suffering heavy casualties and gain time needed for the massive buildup of war industries at home, the Russian Stavka decided to gradually evacuate Galicia and the Polish salient to straighten out the frontline. A strategic retreat was initiated, which is known as the Great Retreat of 1915.

Warsaw was evacuated and fell on 4 August to the new German 12th Army. At the end of the month Poland was entirely in Austro-German hands, and 750,000 Russian prisoners had been taken.

Referencias

Notas

- ↑ Richard L. DiNardo,(2010), p.99

- ↑ Richard L. DiNardo,Breakthrough: The Gorlice-Tarnow Campaign, 1915, (2010), p.99

- ↑ Wolfdieter Bihl, Der Erste Weltkrieg: 1914 - 1918 ; Chronik - Daten - Fakten, 2010, p. 112

- ↑ Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, 2003, p. 212

Bibliografía

- Foley, Robert. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun. Cambridge University Press 2004.

- Graydon J. Tunstall: Blood on the Snow: The Carpathian Winter War of 1915, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, 2010.

- Richard L. DiNardo: Breakthrough: The Gorlice-Tarnow Campaign, Praeger, Santa Barbara, 2010.

Enlaces externos

Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Ofensiva de Gorlice-Tarnów.

Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Ofensiva de Gorlice-Tarnów.- Mapa de Europa al final de la ofensiva de Gorlice-Tarnów en omniatlas.com (en inglés).

- A British observer's account of the Gorlice-Tarnow campaign, 1915 (en inglés).

- Grand Duke Nikolai on the Battle of Gorlice-Tarnow, 3 June 1915 (en inglés).

- German Press Statement on the Opening of the Battle of Gorlice-Tarnow, 2 May 1915 (en inglés).

- WEEK OF SUCCESSES FOR GERMAN ARMS ON EASTERN AND WESTERN BATTLE FRONTS; Defeat in Galicia May Cause Collapse of Carpathian Campaign, NY Times May 9, 1915 (pdf file) (en inglés).