Diferencia entre revisiones de «Usuario:DamyLechu/Taller»

Sin resumen de edición Etiqueta: editor de código 2017 |

|||

| Línea 89: | Línea 89: | ||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

{{div col|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

*[[Adam's Song]] |

*[[Adam's Song]] |

||

*[[Autophobia]] |

*[[Autophobia]] |

||

| Línea 107: | Línea 107: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

---- |

|||

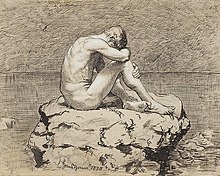

[[Archivo:Frederick_Leighton_-_Solitude.jpg|miniaturadeimagen|''Solitude'' by [[Frederic Leighton, 1st Baron Leighton|Frederic Leighton]]]] |

|||

'''Solitude''' is a state of [[seclusion]] or isolation, i.e., lack of contact with people. It may stem from bad relationships, loss of loved ones, deliberate choice, [[infectious disease]], [[Mental disorder|mental disorders]], [[Circadian rhythm sleep disorder|neurological disorders]] or circumstances of employment or situation (see [[castaway]]). |

|||

Short-term solitude is often valued as a time when one may work, think or rest without being disturbed. It may be desired for the sake of [[privacy]]. |

|||

==External links== |

|||

*{{wikiquote-inline}} |

|||

*{{wikiquote-inline|Solitude}} |

|||

*{{Wiktionary-inline}} |

|||

A distinction has been made between solitude and [[loneliness]]. In this sense, these two words refer, respectively, to the joy and the pain of being alone.<ref>"Our language has wisely sensed the two sides of being alone. It has created the word loneliness to express the pain of being alone. And it has created the word solitude to express the glory of being alone." [[Paul Tillich]]</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=[[Alexander Pope]]|title=Ode on Solitude|url=http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/ode-on-solitude/|accessdate=2016-04-01|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160421125715/http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/ode-on-solitude|archivedate=2016-04-21|df=}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.singlescafe.net/solitude.html|title=The Difference Between Solitude and Loneliness|publisher=Singlescafe.net|accessdate=2013-03-06|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130215035154/http://www.singlescafe.net/solitude.html|archivedate=February 15, 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=Cym|url=http://effortlessflow.blogspot.it/2011/03/difference-between-solitude-and.html|title=Effortless Flow: The Difference Between Solitude and Loneliness|publisher=Effortlessflow.blogspot.it|date=2011-03-02|accessdate=2013-03-06|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130826041537/http://effortlessflow.blogspot.it/2011/03/difference-between-solitude-and.html|archivedate=2013-08-26|df=}}</ref> |

|||

{{emotion-footer}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=February 2015}} |

|||

== Health effects == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Symptoms from complete isolation, called [[sensory deprivation]], often include [[anxiety]], sensory [[Illusion|illusions]], or even distortions of [[time]] and perception. However, this is the case when there is no stimulation of the [[sensory systems]] at all, and not only lack of contact with people. Thus, by having other things to keep one's mind busy, this is avoided.<ref>[http://www.eastandard.net/archives/august/wed25082004/executives/upfront/upfront02.htm]{{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050322131526/http://www.eastandard.net/archives/august/wed25082004/executives/upfront/upfront02.htm|date=March 22, 2005}}</ref> |

|||

Still, long-term solitude is often seen as undesirable, causing [[loneliness]] or [[Recluse|reclusion]] resulting from inability to establish [[Interpersonal relationship|relationships]]. Furthermore, it might even lead to [[clinical depression]]. However, for some people, solitude is not depressing. Still others (e.g. [[Monk|monks]]) regard long-term solitude as a means of spiritual [[Enlightenment (spiritual)|enlightenment]]. Indeed, [[Marooning|marooned]] people have been left in solitude for years without any report of psychological symptoms afterwards.{{Citation needed|date=May 2009}} |

|||

[[Category:Emotional issues]] |

|||

[[Category:Philosophy of love]] |

|||

Enforced loneliness (solitary confinement) has been a punishment method throughout history. It is often considered a form of torture. In contrast, some psychological conditions (such as [[schizophrenia]]<ref>{{Citation|author=Maltsberger, J.T., M. Pompili and R. Tatarelli|title=Sandro Morselli: Schizophrenic Solitude, Suicide, and Psychotherapy|journal=Suicide & Life Threatening Behavior|volume=36|issue=5|pages=591–600|year=2006|pmid=17087638|doi=10.1521/suli.2006.36.5.591|postscript=.}}</ref> and [[schizoid personality disorder]]) are strongly linked to a tendency to seek solitude. In [[Pit of Despair|animal experiments]], solitude has been shown to cause [[psychosis]].{{Dubious|reason=evidence unlikely to support claim|date=January 2017}} |

|||

[[Category:Social issues]] |

|||

[[Category:Emotions]] |

|||

[[Emotional isolation]] is a state of isolation where one has a well-functioning [[social network]] but still feels emotionally separated from others.{{Citation needed|date=January 2017}} |

|||

In the last few years, however, researchers like Robert J. Coplan and Julie C. Bowker have bucked the trend that solitary practices and solitude are inherently dysfunctional and undesirable. In their groundbreaking work ''The Handbook of Solitude'', the authors note how solitude can allow for enhancements in self-esteem, generates clarity, and can be highly therapeutic.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Coplan, Robert J.|first1=Bowker, Julie C.|title=A Handbook of Solitude: Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation|date=2013|publisher=Wiley Blackwell}}</ref> In the edited work, Coplan and Bowker invite not only fellow psychology colleagues to chime in on this issue, but they also invite a variety of other faculty from different disciplines to address the issue. Arguably the most interesting of these alternative views comes from Fong's chapter on how solitude is more than just a personal trajectory for one to take inventory on life; it also yields a variety of important sociological cues that allow the protagonist to navigate through society, even highly politicized societies.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Fong|first1=Jack|title=The Role of Solitude in Transcending Social Crises--New Possibilities for Existential Sociology.|date=2014|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|pages=499–516}}</ref> In the process, political prisoners in solitary confinement were examined to see how they concluded their views on society. Thus Fong, Coplan, and Bowker conclude that a person's experienced solitude generates immanent and personal content as well as collective and sociological content, depending on context. |

|||

== Psychological effects == |

|||

[[Archivo:חסיד_מתבודד.jpg|izquierda|miniaturadeimagen|[[Breslov (Hasidic group)|Breslover]] [[Hasid]] practicing [[hitbodedut]].]] |

|||

There are both positive and negative psychological effects of solitude. Much of the time, these effects and the longevity is determined by the amount of time a person spends in [[Solitary confinement|isolation]].<ref name="first">{{cite web|url=http://www.uplink.com.au/lawlibrary/Documents/Docs/Doc82.html|author=Bartol, C.R., & Bartol, A.M.|year=1994|title=Psychology and Law: Research and Application (2nd ed.)|publisher=Pacific Grove|location=CA: Brooks/Cole.|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20111130075821/http://www.uplink.com.au/lawlibrary/Documents/Docs/Doc82.html|archivedate=November 30, 2011}}</ref> The positive effects can range anywhere from more [[Free will|freedom]] to increased [[spirituality]],<ref name="second">Long, Christopher R. and Averill, James R. “Solitude: An Exploration of the Benefits of Being Alone.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 33:1 (2003): Web. 30 September 2011.</ref> while the negative effects are socially depriving and may trigger the onset of [[mental illness]].<ref name="third">Kupers, Terry A. “What To Do With the Survivors? Coping With the Long-Term Effects of Isolated Confinement”. Criminal Justice and Behavior 35.8 (2008): Web. 30 September 2011.</ref> While positive solitude is often desired, negative solitude is often involuntary or undesired at the time it occurs.<ref name="fourth">{{cite web|last1=Long|first1=Christopher R.|first2=Mary|last2=Seburn|first3=James R.|last3=Averill|first4=Thomas A.|last4=More|title=Solitude Experiences: Varieties, Settings, and Individual Differences|url=http://psp.sagepub.com/|publisher=Sage Publications|date=5 September 2002|accessdate=28 November 2011|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20111204075502/http://psp.sagepub.com/|archivedate=4 December 2011|df=}}</ref> |

|||

=== Positive effects === |

|||

There are many benefits to spending time alone. Freedom is considered to be one of the benefits of solitude; the constraints of others will not have any effect on a person who is spending time in solitude, therefore giving the person more latitude in their actions. With increased freedom, a person’s choices are less likely to be affected by exchanges with others.<ref name="second" /> |

|||

A person's [[creativity]] can be sparked when given freedom. Solitude can increase freedom and moreover, freedom from distractions has the potential to spark creativity. In 1994, psychologist [[Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi]] found that adolescents who cannot bear to be alone often stop enhancing creative talents.<ref name="second" /> |

|||

Another proven benefit to time given in solitude is the development of self. When a person spends time in solitude from others, they may experience changes to their self-concept. This can also help a person to form or discover their identity without any outside distractions. Solitude also provides time for contemplation, growth in personal spirituality, and self-examination. In these situations, loneliness can be avoided as long as the person in solitude knows that they have meaningful relations with others.<ref name="second" /> |

|||

Solitude can be positively used to pray: the devotion of the [[Rosary]] helps the person to pray with a feeling of being accompanied by Jesus and the Virgin Mary in the contemplation of the mysteries of their life with a great sense of peace; the [[Rosary]] fills with prayer the days of many a contemplative, or keeps company with the sick and the elderly.<ref>https://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_letters/2002/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_20021016_rosarium-virginis-mariae.html</ref> |

|||

=== Negative effects === |

|||

Too much solitude is not always considered beneficial. Many of the negative effects have been observed in prisoners. Often, prisoners spend extensive time in solitude, where their behavior may worsen.<ref name="third" /> Solitude can trigger physiological responses that increase health risks.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.psypost.org/2015/11/loneliness-triggers-cellular-changes-that-can-cause-illness-study-shows-39407|title=Loneliness triggers cellular changes that can cause illness, study shows|website=PsyPost|language=en-US|access-date=2016-04-03|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160601175404/http://www.psypost.org/2015/11/loneliness-triggers-cellular-changes-that-can-cause-illness-study-shows-39407|archivedate=2016-06-01|df=}}</ref> |

|||

Negative effects of solitude may also depend on age. Elementary age school children who experience frequent solitude may react negatively.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Larson|first=R. W.|date=1997-02-01|title=The emergence of solitude as a constructive domain of experience in early adolescence|journal=Child Development|volume=68|issue=1|pages=80–93|issn=0009-3920|pmid=9084127|doi=10.2307/1131927}}</ref> This is largely because, often, solitude at this age is not something chosen by the child. Solitude in elementary-age children may occur when they are unsure of how to interact socially with others so they prefer to be alone, causing shyness or social rejection. |

|||

While teenagers are more likely to feel lonely or unhappy when not around others, they are also more likely to have a more enjoyable experience with others if they have had time alone first. However, teenagers who frequently spend time alone do not have as good a global adjustment as those who balance their time of solitude with their social time.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

== Other uses == |

|||

=== As pleasure === |

|||

[[Archivo:Pyle_pirate_marooned.jpg|miniaturadeimagen|[[Howard Pyle]]'s 19th century illustration of a [[Marooning|marooned]] [[pirate]].]] |

|||

Solitude does not necessarily entail feelings of loneliness, and in fact may, for those who choose it with deliberate intent, be one's sole source of genuine pleasure. For example, in religious contexts, some saints preferred silence and found immense pleasure in their perceived uniformity with God. Solitude is a state that can be positively modified utilizing it for [[prayer]] allowing to "be alone with ourselves and with God, to put ourselves in listening to his will, but also of what moves in our hearts, let purify our relationships; solitude and silence thus become spaces inhabited by God, and ability to recover ourselves and grow in humanity. "<ref>{{cite web|url=http://bibbiafrancescana.org/2015/02/preghiera-solitudine-e-silenzio|title=Archived copy|accessdate=2016-10-21|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170617135033/http://bibbiafrancescana.org/2015/02/preghiera-solitudine-e-silenzio/|archivedate=2017-06-17|df=}} /</ref> The Catholic devotion of the Holy [[Rosary]] includes the most beautiful prayers to meditate in solitude the mysteries of Jesus and Virgin Mary's life, feeling in Their company; it’s a devotion to which is associated the [[divine grace]] and that causes an effective change of the emotional and spiritual state.{{Citation needed|date=July 2017}} The Buddha attained enlightenment through uses of meditation, deprived of sensory input, bodily necessities, and external desires, including social interaction. The context of solitude is attainment of pleasure from within, but this does not necessitate complete detachment from the external world. |

|||

[[Archivo:Jacques_Bodin,_De_dos_XXXXV,_oil_on_canvas.jpg|miniaturadeimagen|''Solitude and the Sea'', a theme by Jacques Bodin]] |

|||

This is well demonstrated in the writings of [[Edward Abbey]] with particular regard to ''[[Desert Solitaire]]'' where solitude focused only on isolation from other people allows for a more complete connection to the external world, as in the absence of human interaction the natural world itself takes on the role of the companion. In this context, the individual seeking solitude does so not strictly for personal gain or introspection, though this is often an unavoidable outcome, but instead in an attempt to gain an understanding of the natural world as entirely removed from the human perspective as possible, a state of mind much more readily attained in the complete absence of outside human presence. In psychology, introverted individuals may require spending time away from people to recharge. Those who are simply socially apathetic might find it a pleasurable environment in which to occupy oneself with solitary tasks. |

|||

=== As punishment === |

|||

Isolation in the form of [[solitary confinement]] is a punishment or precaution used in many countries throughout the world for prisoners accused of serious crimes, those who may be at risk in the prison population, those who may commit suicide, or those unable to participate in the prison population due to sickness or injury. Research has found that solitary confinement does not deter inmates from committing further violence in prison.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/03/150331131334.htm|title=Criminologist challenges effectiveness of solitary confinement|website=www.sciencedaily.com|access-date=2016-04-03|deadurl=no|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160603015205/https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/03/150331131334.htm|archivedate=2016-06-03|df=}}</ref> |

|||

=== As treatment === |

|||

[[Psychiatric institution|Psychiatric institutions]] may institute full or partial isolation for certain patients, particularly the violent or subversive, in order to address their particular needs and to protect the rest of the recovering population from their influence. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Hermit]] |

|||

* [[Hikikomori]] |

|||

* [[Hitbodedut]] |

|||

* [[Lone wolf (trait)]] |

|||

* [[Loner]] |

|||

* [[Privacy regulation theory]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Revisión del 00:53 19 oct 2018

Sentimiento negativo de soledad

La soledad como detonante negativo en la vida de una persona, puede ser entendida como una respuesta emocional compleja y generalmente desagradable al aislamiento social. Suele incluir también sentimientos de ansiedad debido a la falta de conexión y/o comunicación con otros individuos, tanto en el presente como en el futuro. Como tal, quien padece de sentimientos de soledad puede sentirse así incluso en presencia de otras personas. Sus causas son variadas e incluyen una amplia cantidad de factores sociales, mentales, emocionales y físicos.

Diversas investigaciones han demostrado que la soledad prevalece en toda sociedad, incluyendo aquellas personas que hayan contraído matrimonios, que estén en una relación amorosa, entre familias, gerontes e incluso personas con carreras exitosas. [1] Ha sido un tema muy explorado por mucho tiempo en la literatura de los seres humanos desde la antigüedad clásica. También se la ha descrito a la soledad como un dolor social (mecanismo psicológico destinado a motivar a una persona a buscar conexiones sociales). [2] En definitiva, se la suele asociar muy a menudo en un contexto de interacción social: "experiencia desagradable que ocurre cuando la red de contactos sociales de un individuo es deficiente de manera significativa". [3]

Causas comunes

Puede haber muchas razones, así como muchos eventos de la vida que pueden causarla. Uno de ellos puede ser la falta de amistades durante la infancia y adolescencia, o la ausencia física de personas significativas. Al mismo tiempo, la soledad puede ser un síntoma de algún otro problema social o psicológico, como la distimia o la fobia social. En ese sentido, puede ser consecuencia de una disfunción de la comunicación, o el resultado de vivir en lugares con baja densidad de población en los que hay pocas personas con las que interactuar.

Muchas personas experimentan la soledad por primera vez al quedarse solos en la primera etapa vital de su vida (cuando son bebés). También es una consecuencia esperable, generalmente temporaria, de una ruptura, un divorcio, un duelo o una pérdida de cualquier relación importante a largo plazo. En estos casos, puede deberse a la pérdida de una persona específica y al consecuente retiro del grupo social debido a la pérdida evento asociada a ella.

Las personas pueden sentirse solas incluso cuando están rodeadas de otras personas.[4] Incluso puede verse como un fenómeno social, capaz de propagarse como una enfermedad. Cuando una persona en un grupo comienza a sentirse sola, este sentimiento (de acuerdo al contexto en que se encuentre) podría propagar a otras personas, lo que aumenta el riesgo de que todos se sientan solos. [5] También puede ocurrir después del nacimiento de un niño (a menudo expresado como una depresión posparto), después del matrimonio o después de cualquier otro evento socialmente perturbador, como mudarse del hogar a una comunidad desconocida, lo que lleva a la nostalgia.

Typology

Feeling lonely vs. being socially isolated

There is a clear distinction between feeling lonely and being socially isolated (for example, a loner). In particular, one way of thinking about loneliness is as a discrepancy between one's necessary and achieved levels of social interaction,[6] while solitude is simply the lack of contact with people. Loneliness is therefore a subjective experience; if a person thinks they are lonely, then they are lonely. People can be lonely while in solitude, or in the middle of a crowd. What makes a person lonely is the fact that they need more social interaction or a certain type of social interaction that is not currently available. A person can be in the middle of a party and feel lonely due to not talking to enough people. Conversely, one can be alone and not feel lonely; even though there is no one around that person is not lonely because there is no desire for social interaction. There have also been suggestions that each person has their own optimal level of social interaction. If a person gets too little or too much social interaction, this could lead to feelings of loneliness or over-stimulation.[7]

Solitude can have positive effects on individuals. One study found that, although time spent alone tended to depress a person's mood and increase feelings of loneliness, it also helped to improve their cognitive state, such as improving concentration. Furthermore, once the alone time was over, people's moods tended to increase significantly.[8] Solitude is also associated with other positive growth experiences, religious experiences, and identity building such as solitary quests used in rites of passages for adolescents.[9]

Loneliness can also play an important role in the creative process. In some people, temporary or prolonged loneliness can lead to notable artistic and creative expression, for example, as was the case with poets Emily Dickinson and Isabella di Morra, and numerous musicians[¿quién?]. This is not to imply that loneliness itself ensures this creativity, rather, it may have an influence on the subject matter of the artist and more likely be present in individuals engaged in creative activities.[cita requerida]

Transient vs. chronic loneliness

The other important typology of loneliness focuses on the time perspective.[10] In this respect, loneliness can be viewed as either transient or chronic. It has also been referred to as state and trait loneliness.

Transient (state) loneliness is temporary in nature, caused by something in the environment, and is easily relieved. Chronic (trait) loneliness is more permanent, caused by the person, and is not easily relieved.[11] For example, when a person is sick and cannot socialize with friends would be a case of transient loneliness. Once the person got better it would be easy for them to alleviate their loneliness. A person who feels lonely regardless of if they are at a family gathering, with friends, or alone is experiencing chronic loneliness. It does not matter what goes on in the surrounding environment, the experience of loneliness is always there.

Loneliness as a human condition

The existentialist school of thought views loneliness as the essence of being human. Each human being comes into the world alone, travels through life as a separate person, and ultimately dies alone. Coping with this, accepting it, and learning how to direct our own lives with some degree of grace and satisfaction is the human condition.[12]

Some philosophers, such as Sartre, believe in an epistemic loneliness in which loneliness is a fundamental part of the human condition because of the paradox between people's consciousness desiring meaning in life and the isolation and nothingness of the universe.[13] Conversely, other existentialist thinkers argue that human beings might be said to actively engage each other and the universe as they communicate and create, and loneliness is merely the feeling of being cut off from this process.

Frequency

There are several estimates and indicators of loneliness. It has been estimated that approximately 60 million people in the United States, or 20% of the total population, feel lonely.[14] Another study found that 12% of Americans have no one with whom to spend free time or to discuss important matters.[15] Other research suggests that this rate has been increasing over time. The General Social Survey found that between 1985 and 2004, the number of people the average American discusses important matters with decreased from three to two. Additionally, the number of Americans with no one to discuss important matters with tripled[16] (though this particular study may be flawed[17]). In the UK research by Age UK shows half a million people more than 60 years old spend each day alone without social interaction and almost half a million more see and speak to no one for 5 or 6 days a week.[18] On the other hand, the Community Life Survey, 2016 to 2017, by the UK's Office for National Statistics, found that young adults in England aged 16 to 24 reported feeling lonely more often than those in older age groups.[19]

Loneliness appears to have intensified in every society in the world as modernization occurs. A certain amount of this loneliness appears to be related to greater migration, smaller household sizes, a larger degree of media consumption (all of which have positive sides as well in the form of more opportunities, more choice in family size, and better access to information), all of which relates to social capital.

Within developed nations, loneliness has shown the largest increases among two groups: seniors[20][21] and people living in low-density suburbs.[22][23] Seniors living in suburban areas are particularly vulnerable, for as they lose the ability to drive, they often become "stranded" and find it difficult to maintain interpersonal relationships.[24]

Loneliness is prevalent in vulnerable groups in society. In New Zealand the fourteen surveyed groups with the highest prevalence of loneliness most/all of the time in descending order are: disabled, recent migrants, low income households, unemployed, single parents, rural (rest of South Island), seniors aged 75+, not in the labour force, youth aged 15-24, no qualifications, not housing owner-occupier, not in a family nucleus, Māori, and low personal income.[25]

Americans seem to report more loneliness than any other country, though this finding may simply be an effect of greater research volume. A 2006 study in the American Sociological Review found that Americans on average had only two close friends in which to confide, which was down from an average of three in 1985. The percentage of people who noted having no such confidant rose from 10% to almost 25%, and an additional 19% said they had only a single confidant, often their spouse, thus raising the risk of serious loneliness if the relationship ended.[26] The modern office environment has been demonstrated to give rise to loneliness. This can be especially prevalent in individuals prone to social isolation who can interpret the business focus of co-workers for a deliberate ignoring of needs.[27]

Whether a correlation exists between Internet usage and loneliness is a subject of controversy, with some findings showing that Internet users are lonelier[28] and others showing that lonely people who use the Internet to keep in touch with loved ones (especially seniors) report less loneliness, but that those trying to make friends online became lonelier.[29] On the other hand, studies in 2002 and 2010 found that "Internet use was found to decrease loneliness and depression significantly, while perceived social support and self-esteem increased significantly"[30] and that the Internet "has an enabling and empowering role in people's lives, by increasing their sense of freedom and control, which has a positive impact on well-being or happiness."[31] The one apparently unequivocal finding of correlation is that long driving commutes correlate with dramatically higher reported feelings of loneliness (as well as other negative health impacts).[32][33]

Effects

Mental health

Loneliness has been linked with depression, and is thus a risk factor for suicide.[34] Émile Durkheim has described loneliness, specifically the inability or unwillingness to live for others, i.e. for friendships or altruistic ideas, as the main reason for what he called egoistic suicide.[35]Plantilla:Unreliable source? In adults, loneliness is a major precipitant of depression and alcoholism.[36] People who are socially isolated may report poor sleep quality, and thus have diminished restorative processes.[37] Loneliness has also been linked with a schizoid character type in which one may see the world differently and experience social alienation, described as the self in exile.[38]

In children, a lack of social connections is directly linked to several forms of antisocial and self-destructive behavior, most notably hostile and delinquent behavior. In both children and adults, loneliness often has a negative impact on learning and memory. Its disruption of sleep patterns can have a significant impact on the ability to function in everyday life.[34]

Research from a large-scale study published in the journal Psychological Medicine, showed that "lonely millennials are more likely to have mental health problems, be out of work and feel pessimistic about their ability to succeed in life than their peers who feel connected to others, regardless of gender or wealth".[39][40]

Pain, depression, and fatigue function as a symptom cluster and thus may share common risk factors. Two longitudinal studies with different populations demonstrated that loneliness was a risk factor for the development of the pain, depression, and fatigue symptom cluster over time. These data also highlight the health risks of loneliness; pain, depression, and fatigue often accompany serious illness and place people at risk for poor health and mortality.[41]

Physical health

Chronic loneliness can be a serious, life-threatening health condition. It has been found to be associated with an increased risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease.[42] Loneliness shows an increased incidence of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and obesity.[43]

Loneliness is shown to increase the concentration of cortisol levels in the body.[43] Prolonged, high cortisol levels can cause anxiety, depression, digestive problems, heart disease, sleep problems, and weight gain.[44]

″Loneliness has been associated with impaired cellular immunity as reflected in lower natural killer (NK) cell activity and higher antibody titers to the Epstein Barr Virus and human herpes viruses".[43] Because of impaired cellular immunity, loneliness among young adults shows vaccines, like the flu vaccine, to be less effective.[43] Data from studies on loneliness and HIV positive men suggests loneliness increases disease progression.[43]

Physiological mechanisms link to poor health

There are a number of potential physiological mechanisms linking loneliness to poor health outcomes. In 2005, results from the American Framingham Heart Study demonstrated that lonely men had raised levels of Interleukin 6 (IL-6), a blood chemical linked to heart disease. A 2006 study conducted by the Center for Cognitive and Social Neuroscience at the University of Chicago found loneliness can add thirty points to a blood pressure reading for adults over the age of fifty. Another finding, from a survey conducted by John Cacioppo from the University of Chicago, is that doctors report providing better medical care to patients who have a strong network of family and friends than they do to patients who are alone. Cacioppo states that loneliness impairs cognition and willpower, alters DNA transcription in immune cells, and leads over time to high blood pressure.[14] Lonelier people are more likely to show evidence of viral reactivation than less lonely people.[45] Lonelier people also have stronger inflammatory responses to acute stress compared with less lonely people; inflammation is a well known risk factor for age-related diseases.[46]

When someone feels left out of a situation, they feel excluded and one possible side effect is for their body temperature to decrease. When people feel excluded blood vessels at the periphery of the body may narrow, preserving core body heat. This class protective mechanism is known as vasoconstriction.[47]

Treatments and prevention

There are many different ways used to treat loneliness, social isolation, and clinical depression. The first step that most doctors recommend to patients is therapy. Therapy is a common and effective way of treating loneliness and is often successful. Short-term therapy, the most common form for lonely or depressed patients, typically occurs over a period of ten to twenty weeks. During therapy, emphasis is put on understanding the cause of the problem, reversing the negative thoughts, feelings, and attitudes resulting from the problem, and exploring ways to help the patient feel connected. Some doctors also recommend group therapy as a means to connect with other sufferers and establish a support system.[48] Doctors also frequently prescribe anti-depressants to patients as a stand-alone treatment, or in conjunction with therapy. It may take several attempts before a suitable anti-depressant medication is found.[49]

Alternative approaches to treating depression are suggested by many doctors. These treatments include exercise, dieting, hypnosis, electro-shock therapy, acupuncture, and herbs, amongst others. Many patients find that participating in these activities fully or partially alleviates symptoms related to depression.[50]

Another treatment for both loneliness and depression is pet therapy, or animal-assisted therapy, as it is more formally known. Studies and surveys, as well as anecdotal evidence provided by volunteer and community organizations, indicate that the presence of animal companions such as dogs, cats, rabbits, and guinea pigs can ease feelings of depression and loneliness among some sufferers. Beyond the companionship the animal itself provides there may also be increased opportunities for socializing with other pet owners. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention there are a number of other health benefits associated with pet ownership, including lowered blood pressure and decreased levels of cholesterol and triglycerides.[51]

Nostalgia has also been found to have a restorative effect, counteracting loneliness by increasing perceived social support.[52]

A 1989 study found that the social aspect of religion had a significant negative association with loneliness among elderly people. The effect was more consistent than the effect of social relationships with family and friends, and the subjective concept of religiosity had no significant effect on loneliness.[53]

One study compared the effectiveness of four interventions: improving social skills, enhancing social support, increasing opportunities for social interaction, addressing abnormal social cognition (faulty thoughts and patterns of thoughts). The results of the study indicated that all interventions were effective in reducing loneliness, possibly with the exception of social skill training. Results of the meta-analysis suggest that correcting maladaptive social cognition offers the best chance of reducing loneliness.[54]

See also

- Adam's Song

- Autophobia

- Eleanor Rigby

- Individualism

- Interpersonal relationship

- Loner

- Pit of despair (animal experiments on isolation)

- Solitude

- Shyness

- Social anxiety

- Social anxiety disorder

- Social isolation

- Schizoid personality disorder

|}

References

- ↑ Peplau, L.A.; Perlman, D. (1982). «Perspectives on loneliness». En Peplau, Letitia Anne, ed. Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 1-18. ISBN 978-0-471-08028-2.

- ↑ Cacioppo, John; Patrick, William, Loneliness: Naturaleza Humana y la Necesidad para Conexión Social, Nueva York : W.W. Norton & Co., 2008.

- ↑ Pittman, Matthew; Reich, Brandon (2016). «Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words». Computers in Human Behavior 62: 155-167. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.084.

- ↑ «Feeling Alone Together: How Loneliness Spreads». Time.com. 1 de diciembre de 2009. Consultado el 10 de diciembre de 2012.

- ↑ Parker, Pope (1 de diciembre de 2009). «Why loneliness can be contagious». Consultado el 10 de diciembre de 2012.

- ↑ Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; no se ha definido el contenido de las referencias llamadasPeplau, L.A. 1982 pp. 1-18 - ↑ Suedfeld, P. (1989). «Past the reflection and through the looking-glass: Extending loneliness research». En Hojat, M.; Crandall, R., eds. Loneliness: Theory, research and applications. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications. pp. 51-6.

- ↑ Larson, R.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Graef, R. (1982). «Time alone in daily experience: Loneliness or renewal?». En Peplau, Letitia Anne; Perlman, Daniel, eds. Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 41-53. ISBN 978-0-471-08028-2.

- ↑ Suedfeld, P. (1982). «Aloneness as a healing experience». En Peplau, Letitia Anne; Perlman, Daniel, eds. Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 54-67. ISBN 978-0-471-08028-2.

- ↑ de Jong-Gierveld, J.; Raadschelders, J. (1982). «Types of loneliness». En Peplau, Letitia Anne; Perlman, Daniel, eds. Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 105-19. ISBN 978-0-471-08028-2.

- ↑ Duck, S. (1992). Human relations (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- ↑ An Existential View of Loneliness - Carter, Michele; excerpt from Abiding Loneliness: An Existential Perspective, Park Ridge Center, September 2000

- ↑ Tomšik, Robert (2015). Relationship of loneliness and meaning of life among adolescents. In Current Trends in Educational Science and Practice VIII : International Proceedings of Scientific Studies. Nitra: UKF. pp. 66-7. ISBN 978-80-558-0813-0.

- ↑ a b Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; no se ha definido el contenido de las referencias llamadasScience of Loneliness.com - ↑ Christakis, N. A. & Fowler, J. H. (2009). Connected: The surprising power of our social networks and how they shape our lives. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company.[página requerida]

- ↑ Olds, J. & Schwartz, R. S. (2009). The lonely American: Drifting apart in the 21st century. Boston, MA: Beacon Press[página requerida]

- ↑ Fischer, Claude S. (2009). «The 2004 GSS Finding of Shrunken Social Networks: An Artifact?». sagepub.com 74 (4): 657-669. doi:10.1177/000312240907400408.

- ↑ Half a million older people spend every day alone, poll shows The Guardian

- ↑ Loneliness - What characteristics and circumstances are associated with feeling lonely? Analysis of characteristics and circumstances associated with loneliness in England using the Community Life Survey, 2016 to 2017. Published by the Office for National Statistics. Published 10 April 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ «Most Senior Citizens Experience Loneliness, Say Researchers». Archivado desde el original el 26 December 2011. Consultado el 19 de agosto de 2012. Parámetro desconocido

|df=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Archived copy». Archivado desde el original el 15 August 2013. Consultado el 25 de marzo de 2012. Parámetro desconocido

|df=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Isolation and Dissatisfaction in the Suburbs». Planetizen: The Urban Planning, Design, and Development Network.

- ↑ http://www.geog.ubc.ca/~ewyly/u200/suburbia.pdf

- ↑ «Stranded Seniors». governing.com.

- ↑ Comber, Cathy. «Ms». www.loneliness.org.nz. Consultado el 8 October 2018.

- ↑ McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Brashears, M. E. (2006). «Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks over Two Decades». American Sociological Review 71 (3): 353-75. doi:10.1177/000312240607100301. Parámetro desconocido

|citeseerx=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Wright, Sarah (16 de mayo de 2008). Loneliness in the Workplace. VDM Verlag Dr. Mull Ed Beasleyschaft & Co. ISBN 978-3-639-02734-1.[página requerida]

- ↑ Hughes, Carole (1999). The relationship of use of the Internet and loneliness among college students (PhD Thesis). Boston College. OCLC 313894784.[página requerida]

- ↑ Sum, Shima; Mathews, R. Mark; Hughes, Ian; Campbell, Andrew (2008). «Internet Use and Loneliness in Older Adults». CyberPsychology & Behavior 11 (2): 208-11. PMID 18422415. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.0010.

- ↑ Shaw, Lindsay H.; Gant, Larry M. (2002). «In Defense of the Internet: The Relationship between Internet Communication and Depression, Loneliness, Self-Esteem, and Perceived Social Support». CyberPsychology & Behavior 5 (2): 157-71. PMID 12025883. doi:10.1089/109493102753770552. Parámetro desconocido

|citeseerx=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Is the Internet the Secret to Happiness?». Time. 14 de mayo de 2010.

- ↑ http://www.slate.com/articles/business/moneybox/2011/05/your_commute_is_killing_you.htmlPlantilla:Full citation needed

- ↑ http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/04/16/070416fa_fact_paumgarten?currentPage=3Plantilla:Full citation needed

- ↑ a b The Dangers of Loneliness - Marano, Hara Estroff; Psychology Today Thursday 21 August 2003

- ↑ Shelkova, Polina (2010). «Loneliness».

- ↑ Marano, Hara. «The Dangers of Loneliness». Consultado el 10 December 2012.

- ↑ Hawkley, Louise C; Cacioppo, John T (2003). «Loneliness and pathways to disease». Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 17 (1): 98-105. PMID 12615193. doi:10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00073-9.

- ↑ Masterson, James F.; Klein, Ralph (1995). Disorders of the Self: Secret Pure Schizoid Cluster Disorder. pp. 25-7. «Klein was Clinical Director of the Masterson Institute and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York».

- ↑ Loneliness linked to major life setbacks for millennials, study says. The Guardian. Author - Nicola Davis. Published 24 April 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Lonely young adults in modern Britain: findings from an epidemiological cohort study. Psychological Medicine. Authors - Timothy Matthews (a1), Andrea Danese (a1) (a2), Avshalom Caspi (a1) (a3), Helen L. Fisher (a1), Sidra Goldman-Mellor (a4), Agnieszka Kepa (a1), Terrie E. Moffitt (a1) (a3), Candice L. Odgers (a5) (a6) and Louise Arseneault (a1). Published online on 24 April 2018. Published by Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Jaremka, L.M., Andridge, R.R., Fagundes, C.P., Alfano, C.M., Povoski, S.P., Lipari, A.M., Agnese, D.M., Arnold, M.W., Farrar, W.B., Yee, L.D. Carson III, W.E., Bekaii-Saab, T., Martin Jr, E.W., Schmidt, C.R., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. (2014). Pain, depression, and fatigue: Loneliness as a longitudinal risk factor. Health Psychology, 38, 1310-1317.

- ↑ «Loneliness and Isolation: Modern Health Risks». The Pfizer Journal IV (4). 2000. Archivado desde el original el 28 January 2006.

- ↑ a b c d e Cacioppo, J.; Hawkley, L. (2010). «Loneliness Matters: A Theorectical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms». Annals of Behavioral Medicine 40 (2): 218-227.

- ↑ «Chronic stress puts your health at risk». Consultado el 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Jaremka, Lisa M.; Fagundes, Christopher P.; Glaser, Ronald; Bennett, Jeanette M.; Malarkey, William B.; Kiecolt-Glaser, Janice K. (2013). «Loneliness predicts pain, depression, and fatigue: Understanding the role of immune dysregulation». Psychoneuroendocrinology 38 (8): 1310-7. PMC 3633610. PMID 23273678. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.11.016.

- ↑ Jaremka, Lisa M.; Fagundes, Christopher P.; Peng, Juan; Bennett, Jeanette M.; Glaser, Ronald; Malarkey, William B.; Kiecolt-Glaser, Janice K. (2013). «Loneliness Promotes Inflammation During Acute Stress». Psychological Science 24 (7): 1089-97. PMC 3825089. PMID 23630220. doi:10.1177/0956797612464059.

- ↑ Ijzerman, Hans. «Getting the cold shoulder». The New York Times. Consultado el 1 November 2012.

- ↑ «Psychotherapy». Depression.com. Consultado el 29 March 2008.

- ↑ «The Truth About Antidepressants». WebMD. Consultado el 30 March 2008.

- ↑ «Alternative treatments for depression». WebMD. Consultado el 30 March 2008.

- ↑ Health Benefits of Pets (from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ↑ Zhou, Xinyue; Sedikides, Constantine; Wildschut, Tim; Gao, Ding-Guo (2008). «Counteracting Loneliness: On the Restorative Function of Nostalgia». Psychological Science 19 (10): 1023-9. PMID 19000213. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02194.x.

- ↑ Johnson, D. P.; Mullins, L. C. (1989). «Religiosity and Loneliness Among the Elderly». Journal of Applied Gerontology 8: 110-31. doi:10.1177/073346488900800109.

- ↑ Masi, C. M.; Chen, H.-Y.; Hawkley, L. C.; Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). «A Meta-Analysis of Interventions to Reduce Loneliness». Personality and Social Psychology Review 15 (3): 219-66. PMC 3865701. PMID 20716644. doi:10.1177/1088868310377394.

Solitude is a state of seclusion or isolation, i.e., lack of contact with people. It may stem from bad relationships, loss of loved ones, deliberate choice, infectious disease, mental disorders, neurological disorders or circumstances of employment or situation (see castaway).

Short-term solitude is often valued as a time when one may work, think or rest without being disturbed. It may be desired for the sake of privacy.

A distinction has been made between solitude and loneliness. In this sense, these two words refer, respectively, to the joy and the pain of being alone.[1][2][3][4]

Health effects

Symptoms from complete isolation, called sensory deprivation, often include anxiety, sensory illusions, or even distortions of time and perception. However, this is the case when there is no stimulation of the sensory systems at all, and not only lack of contact with people. Thus, by having other things to keep one's mind busy, this is avoided.[5]

Still, long-term solitude is often seen as undesirable, causing loneliness or reclusion resulting from inability to establish relationships. Furthermore, it might even lead to clinical depression. However, for some people, solitude is not depressing. Still others (e.g. monks) regard long-term solitude as a means of spiritual enlightenment. Indeed, marooned people have been left in solitude for years without any report of psychological symptoms afterwards.[cita requerida]

Enforced loneliness (solitary confinement) has been a punishment method throughout history. It is often considered a form of torture. In contrast, some psychological conditions (such as schizophrenia[6] and schizoid personality disorder) are strongly linked to a tendency to seek solitude. In animal experiments, solitude has been shown to cause psychosis.[cita requerida]

Emotional isolation is a state of isolation where one has a well-functioning social network but still feels emotionally separated from others.[cita requerida]

In the last few years, however, researchers like Robert J. Coplan and Julie C. Bowker have bucked the trend that solitary practices and solitude are inherently dysfunctional and undesirable. In their groundbreaking work The Handbook of Solitude, the authors note how solitude can allow for enhancements in self-esteem, generates clarity, and can be highly therapeutic.[7] In the edited work, Coplan and Bowker invite not only fellow psychology colleagues to chime in on this issue, but they also invite a variety of other faculty from different disciplines to address the issue. Arguably the most interesting of these alternative views comes from Fong's chapter on how solitude is more than just a personal trajectory for one to take inventory on life; it also yields a variety of important sociological cues that allow the protagonist to navigate through society, even highly politicized societies.[8] In the process, political prisoners in solitary confinement were examined to see how they concluded their views on society. Thus Fong, Coplan, and Bowker conclude that a person's experienced solitude generates immanent and personal content as well as collective and sociological content, depending on context.

Psychological effects

There are both positive and negative psychological effects of solitude. Much of the time, these effects and the longevity is determined by the amount of time a person spends in isolation.[9] The positive effects can range anywhere from more freedom to increased spirituality,[10] while the negative effects are socially depriving and may trigger the onset of mental illness.[11] While positive solitude is often desired, negative solitude is often involuntary or undesired at the time it occurs.[12]

Positive effects

There are many benefits to spending time alone. Freedom is considered to be one of the benefits of solitude; the constraints of others will not have any effect on a person who is spending time in solitude, therefore giving the person more latitude in their actions. With increased freedom, a person’s choices are less likely to be affected by exchanges with others.[10]

A person's creativity can be sparked when given freedom. Solitude can increase freedom and moreover, freedom from distractions has the potential to spark creativity. In 1994, psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi found that adolescents who cannot bear to be alone often stop enhancing creative talents.[10]

Another proven benefit to time given in solitude is the development of self. When a person spends time in solitude from others, they may experience changes to their self-concept. This can also help a person to form or discover their identity without any outside distractions. Solitude also provides time for contemplation, growth in personal spirituality, and self-examination. In these situations, loneliness can be avoided as long as the person in solitude knows that they have meaningful relations with others.[10]

Solitude can be positively used to pray: the devotion of the Rosary helps the person to pray with a feeling of being accompanied by Jesus and the Virgin Mary in the contemplation of the mysteries of their life with a great sense of peace; the Rosary fills with prayer the days of many a contemplative, or keeps company with the sick and the elderly.[13]

Negative effects

Too much solitude is not always considered beneficial. Many of the negative effects have been observed in prisoners. Often, prisoners spend extensive time in solitude, where their behavior may worsen.[11] Solitude can trigger physiological responses that increase health risks.[14]

Negative effects of solitude may also depend on age. Elementary age school children who experience frequent solitude may react negatively.[15] This is largely because, often, solitude at this age is not something chosen by the child. Solitude in elementary-age children may occur when they are unsure of how to interact socially with others so they prefer to be alone, causing shyness or social rejection.

While teenagers are more likely to feel lonely or unhappy when not around others, they are also more likely to have a more enjoyable experience with others if they have had time alone first. However, teenagers who frequently spend time alone do not have as good a global adjustment as those who balance their time of solitude with their social time.[15]

Other uses

As pleasure

Solitude does not necessarily entail feelings of loneliness, and in fact may, for those who choose it with deliberate intent, be one's sole source of genuine pleasure. For example, in religious contexts, some saints preferred silence and found immense pleasure in their perceived uniformity with God. Solitude is a state that can be positively modified utilizing it for prayer allowing to "be alone with ourselves and with God, to put ourselves in listening to his will, but also of what moves in our hearts, let purify our relationships; solitude and silence thus become spaces inhabited by God, and ability to recover ourselves and grow in humanity. "[16] The Catholic devotion of the Holy Rosary includes the most beautiful prayers to meditate in solitude the mysteries of Jesus and Virgin Mary's life, feeling in Their company; it’s a devotion to which is associated the divine grace and that causes an effective change of the emotional and spiritual state.[cita requerida] The Buddha attained enlightenment through uses of meditation, deprived of sensory input, bodily necessities, and external desires, including social interaction. The context of solitude is attainment of pleasure from within, but this does not necessitate complete detachment from the external world.

This is well demonstrated in the writings of Edward Abbey with particular regard to Desert Solitaire where solitude focused only on isolation from other people allows for a more complete connection to the external world, as in the absence of human interaction the natural world itself takes on the role of the companion. In this context, the individual seeking solitude does so not strictly for personal gain or introspection, though this is often an unavoidable outcome, but instead in an attempt to gain an understanding of the natural world as entirely removed from the human perspective as possible, a state of mind much more readily attained in the complete absence of outside human presence. In psychology, introverted individuals may require spending time away from people to recharge. Those who are simply socially apathetic might find it a pleasurable environment in which to occupy oneself with solitary tasks.

As punishment

Isolation in the form of solitary confinement is a punishment or precaution used in many countries throughout the world for prisoners accused of serious crimes, those who may be at risk in the prison population, those who may commit suicide, or those unable to participate in the prison population due to sickness or injury. Research has found that solitary confinement does not deter inmates from committing further violence in prison.[17]

As treatment

Psychiatric institutions may institute full or partial isolation for certain patients, particularly the violent or subversive, in order to address their particular needs and to protect the rest of the recovering population from their influence.

See also

References

- ↑ "Our language has wisely sensed the two sides of being alone. It has created the word loneliness to express the pain of being alone. And it has created the word solitude to express the glory of being alone." Paul Tillich

- ↑ Alexander Pope. «Ode on Solitude». Archivado desde el original el 21 de abril de 2016. Consultado el 1 de abril de 2016.

- ↑ «The Difference Between Solitude and Loneliness». Singlescafe.net. Archivado desde el original el February 15, 2013. Consultado el 6 de marzo de 2013.

- ↑ Cym (2 de marzo de 2011). «Effortless Flow: The Difference Between Solitude and Loneliness». Effortlessflow.blogspot.it. Archivado desde el original el 26 de agosto de 2013. Consultado el 6 de marzo de 2013.

- ↑ [1] (enlace roto disponible en este archivo).

- ↑ Maltsberger, J.T., M. Pompili and R. Tatarelli (2006), «Sandro Morselli: Schizophrenic Solitude, Suicide, and Psychotherapy», Suicide & Life Threatening Behavior 36 (5): 591-600, PMID 17087638, doi:10.1521/suli.2006.36.5.591..

- ↑ Coplan, Robert J., Bowker, Julie C. (2013). A Handbook of Solitude: Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation. Wiley Blackwell.

- ↑ Fong, Jack (2014). The Role of Solitude in Transcending Social Crises--New Possibilities for Existential Sociology. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 499-516.

- ↑ Bartol, C.R., & Bartol, A.M. (1994). «Psychology and Law: Research and Application (2nd ed.)». CA: Brooks/Cole.: Pacific Grove. Archivado desde el original el November 30, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d Long, Christopher R. and Averill, James R. “Solitude: An Exploration of the Benefits of Being Alone.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 33:1 (2003): Web. 30 September 2011.

- ↑ a b Kupers, Terry A. “What To Do With the Survivors? Coping With the Long-Term Effects of Isolated Confinement”. Criminal Justice and Behavior 35.8 (2008): Web. 30 September 2011.

- ↑ Long, Christopher R.; Seburn, Mary; Averill, James R.; More, Thomas A. (5 September 2002). «Solitude Experiences: Varieties, Settings, and Individual Differences». Sage Publications. Archivado desde el original el 4 December 2011. Consultado el 28 November 2011.

- ↑ https://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_letters/2002/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_20021016_rosarium-virginis-mariae.html

- ↑ «Loneliness triggers cellular changes that can cause illness, study shows». PsyPost (en inglés estadounidense). Archivado desde el original el 1 de junio de 2016. Consultado el 3 de abril de 2016.

- ↑ a b Larson, R. W. (1 de febrero de 1997). «The emergence of solitude as a constructive domain of experience in early adolescence». Child Development 68 (1): 80-93. ISSN 0009-3920. PMID 9084127. doi:10.2307/1131927.

- ↑ «Archived copy». Archivado desde el original el 17 de junio de 2017. Consultado el 21 de octubre de 2016. /

- ↑ «Criminologist challenges effectiveness of solitary confinement». www.sciencedaily.com. Archivado desde el original el 3 de junio de 2016. Consultado el 3 de abril de 2016.