Usuario:Edgarbl3/Phage Therapy

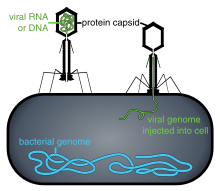

La terapia de fagos o terapia viral de fagos es una terapia que utiliza bacteriófagos para tratar infecciones bacterianas patogénicas.[1] La terapia de fagos tiene muchas aplicaciones para la medicina del ser humano, así como para odontología, ciencia, veterinaria y agricultura.[2] Si el sujeto de un tratamiento de terapia de fagos no es un animal, el término “biocontrol” (como en un biocontrol mediante fagos) es el utilizado comúnmente.

Esta terapia tiene un alto índice terapéutico, es decir, que se espera que la terapia de fagos de pie a algunos efectos secundarios. Ya que los fagos se replican in vivo, se pueden usar con eficacia en pequeñas dosis. Por otro lado, esta característica también es una desventaja; ya que un fago solamente matará a una bacteria si esta contiene cierta cepa. Consecuentemente, una variedad de fagos es utilizada para incrementar las probabilidades de éxito, o se obtienen muestras previas para identificar y cultivar a los fagos apropiados.

Los bacteriófagos tienen un objetivo más específico que los antibióticos. Son usualmente inofensivos, no sólo para los organismos del sujeto, sino que también para otros tipos de flora normal, como la que se encuentran en los intestinos; esto con el fin de reducir el riesgo de otra infección..[3]

Los fagos tienden a ser más exitosos que los antibióticos en presencia de una biopelícula cubierta por una capa de polisacáridos, la cual usualmente no puede ser traspasada por un antibiótico.[4] En occidente, ninguna de estas terapias está autorizada para ser utilizada en seres humanos, aunque ya están en uso fagos para el tratamiento contra intoxicaciones alimentarias causadas por bacterias (Listeria)..[5]

Actualmente los fagos son utilizados para tratar infecciones bacterianas que no responden a los antibióticos convencionales, esto ocurre particularmente en Rusia[6] y Georgia.[7][8][9] También, desde 2005, existe una unidad de terapia de fagos en Breslavia, Polonia; el único en su tipo dentro de la Unión Europea.[10]

Historia[editar]

El descubrimiento de los bacteriofagos fue reportado por Frederick Twort en 1915 y por Felix d´Hérelle en 1917[11]. D´Hérelle observó que los fagos siempre aparecían en las sillas de los pacientes en recuperación de disentería causada por shigelosis,[12] debido a esto, pronto aprendió que los bacteriófagos se encontraban en donde los bacterias se desarrollan con facilidad, como en: drenajes, ríos contaminados por los sistemas de deshechos y en las sillas de los pacientes convalecientes.[13] La terapia de fagos fue rápidamente reconocida por varios científicos como una alternativa clave para la erradicación de infecciones bacterianas. Un investigador georgiano, George Eliava, estaba realizando descubrimientos similares, por lo que viajó al Instituto Pasteur en París, donde conoció a d´Hérelle. Posteriormente fundó en 1923 el Instituto Eliava en Tiflis, Georgia, esta institución fue destinada al desarrollo de la terapia de fagos. La terapia de fagos es utilizada en Rusia, Georgia y Polonia.

En Rusia, está por comenzar una extensa investigación en el desarrollo de este campo. En los Estados Unidos durante los 1940, la comercialización de la terapia de fagos estaba a cargo de Eli Lilly and Company.

Mientras se adquiere conocimiento respecto a la biología de los fagos y a como usar correctamente mezclas de estos mismos, los primeros usos de esta técnica fueron usualmente poco fiables.[14] Cuando los antibióticos fueron descubiertos y comercializados por E.U.A y Europa en 1941, los científicos occidentales perdieron temporalmente el interés en el estudio y el uso de la terapia de fagos.[15]

Aislada de los avances occidentales en la producción de antibióticos de los años 40, científicos rusos continuaron con el proceso de desarrollo de terapias de fagos exitosas para tratar en hospitales de campaña a soldados heridos. Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la Unión Soviética usaba bacteriófagos para tratar a soldados con distintas infecciones bacterianas, como por ejemplo: la disentería y la gangrena. Investigadores rusos continuaron en el desarrollo y refinamiento de los tratamientos, posteriormente publicaron sus investigaciones y resultados. Sin embargo, debido a las barreras científicas de la Guerra Fría, estas investigaciones no fueron traducidas y no proliferaron en el mundo.[16][17] Un resumen de estas indagaciones fue publicado en inglés en el año de 2009, en “A Literature Review of the Practice Application of Bacteriophage Research”.[18]

Hay una extensa biblioteca e investigación en el instituto George Eliava en Tiflis, Georgia. Hoy en día la terapia de fagos es un tratamiento popular en esta región.[19]

Como resultado del incremento a la resistencia a los antibióticos desde 1950 y el avance en el conocimiento científico, ha renacido en todo el mundo el interés por estudiar las habilidades de la terapia de fagos para erradicar infecciones bacterianas.[20]

Los fagos son investigados por su potencial para eliminar patógenos como la Campylobacter, la cual se encuentra en la comida cruda, y la Listeria, la cual se encuentra en comida fresca; o con el propósito de reducir el proceso de descomposición a causa de bacterias de la comida.[21] En la agricultura los fagos eran usados para combatir patógenos como la Campylobacter, la Escherichia y la Salmonella en el ganado; los Lactococcus y Vibrio que se encuentran en los pescados criados en acuicultura; y la Erwinia y Xanthomonas en plantas de importancia agrícola. Sin embargo, el uso más viejo de esta terapia es la medicina humana. Los fagos han sido usados contra enfermedades diarreicas causadas por E.coli, Shigella o Vibrio y contra infecciones en heridas causadas por patógenos de la piel como staphylococcus y streptococcus. Recientemente la terapia de fagos ha sido aplicada en infecciones sistémicas e intracelulares; a la agregación de fagos que no se replican; y al aislamiento de enzimas de fagos, como la lisina. Sin embargo, no existen verdaderas pruebas de campo o en el hospital que demuestren la eficacia de estos métodos de terapia de fagos.[21]

Algunos de los avances occidentales respecto al tema datan de 1994, cuando Soothill demostró (en un modelo con animales) que el uso de fagos reducía la posibilidad de una infección por Pseudomonas aeruginosa en operaciones de injerto de piel.[22] Estudios recientes respaldan estos descubrimientos en un modelo del sistema.[23]

Aunque no es en esencia “terapia de fagos”, el uso de fagos como mecanismo de distribución para antibióticos tradicionales es otro de los posibles usos terapéuticos.[24][25] El uso de fagos para distribuir agentes antitumorales ha sido descrito preliminarmente en experimentos in vitro en células de cultivos de tejido.[26]

En junio de 2015 la Agencia Europea de Medicamentos organizó un taller de un día dedicado al uso terapéutico de bacteriófagos[27] y en julio de 2015 el Instituto Nacional de la Salud (EUA) organizó un taller de dos días titulado “ Terapia Bacteriófaga: Una Estrategia Alternativa para Combatir la Resistencia a los Medicamentos.[28]

Beneficios potenciales[editar]

El tratamiento con bacteriófagos ofrece una alternativa al uso de antibióticos convencionales para el tratamiento de infecciones bacterianas.[29] Es probable que, aunque las bacterias pueden desarrollar resistencia a los fagos, esta resistencia es más fácil de superar que la resistencia a los antibióticos.[30] Así como las bacterias pueden evolucionar para obtener resistencia, los viruses puede evolucionar para superar la resistencia. [31]

Los bacteriófagos son muy específicos, sólo se enfocan en una o pocas cepas de una bacteria.[32] Los antibióticos tradicionales tienen una mayor variedad de efectos, matando de esta manera a bacterias dañinas, así como a bacterias útiles, como las que nos facilitan la digestión de alimentos. Las especies y cepas específicas de los bacteriófagos reducen la posibilidad de matar bacterias no dañinas mientras se trata una infección.

Alguna evidencia demuestra la habilidad de los fagos para llegar al sitio de acción requerido (incluyendo el cerebro, donde los fagos pueden traspasar la barrera hematoencefálica) al igual que pueden multiplicarse en presencia del huésped bacteriano apropiado, para así combatir infecciones como la meningitis. Sin embargo, el sistema inmune del paciente puede, en algunos casos, generar una respuesta inmune al fago (2 de cada 44 pacientes de acuerdo a un estudio polaco[33]).

Pocos grupos de investigación occidentales están desarrollando un mayor rango de fagos, así como una mayor variedad de formas de tratamiento para Staphylococcus aureus resistentes a la meticilina (SARM); esto incluye injertos de piel en heridas, tratamiento preventivo para víctimas de quemaduras y suturas fago impregnadas.[34] Un nuevo proyecto de la Universidad Rockefeller son los enzibióticos, los cuales crean enzimas a partir de fagos. Estos nuevos medicamentos muestra potencial para prevenir infecciones bacterianas secundarias como el desarrollo de neumonía en pacientes con gripe y otitis.[cita requerida] Las enzimas recombinantes y purificadas de los fagos pueden usarse por separado como agentes antibacteriales.[35]

Para algunas bacterias, como la multi-resistente Klebsiella pneumoniae, no hay antibióticos efectivos que no sean tóxicos, pero la erradicación de esta bacteria a través de fagos vía intraperitoneal, intravenosa o intranasal, ha mostrado resultados en las pruebas de laboratorio.[36]

Application[editar]

Collection[editar]

The simplest method of phage treatment involves collecting local samples of water likely to contain high quantities of bacteria and bacteriophages, for example effluent outlets, sewage and other sources.[7] They can also be extracted from corpses.[cita requerida] The samples are taken and applied to the bacteria that are to be destroyed which have been cultured on growth medium.

If the bacteria die, as usually happens, the mixture is centrifuged; the phages collect on the top of the mixture and can be drawn off.

The phage solutions are then tested to see which ones show growth suppression effects (lysogeny) or destruction (lysis) of the target bacteria. The phage showing lysis are then amplified on cultures of the target bacteria, passed through a filter to remove all but the phages, then distributed.

Treatment[editar]

Phages are "bacterium-specific" and it is therefore necessary in many cases to take a swab from the patient and culture it prior to treatment. Occasionally, isolation of therapeutic phages can require a few months to complete, but clinics generally keep supplies of phage cocktails for the most common bacterial strains in a geographical area.

Phages in practice are applied orally, topically on infected wounds or spread onto surfaces, or used during surgical procedures. Injection is rarely used, avoiding any risks of trace chemical contaminants that may be present from the bacteria amplification stage, and recognizing that the immune system naturally fights against viruses introduced into the bloodstream or lymphatic system.

The direct human use of phages is likely to be very safe; in August and October 2006, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved spraying meat and cheese with phages. The approval was for ListShield and Listex (phage preparations targeting Listeria monocytogenes). These were the first approvals granted by the FDA and USDA for phage-based applications. This confirmation of safety within the worldwide scientific community opened the way for other phages applications for example against Salmonella and E-coli (http://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/regulations/directives/fsis-directives)

Phage therapy has been attempted for the treatment of a variety of bacterial infections including: laryngitis, skin infections, dysentery, conjunctivitis, periodontitis, gingivitis, sinusitis, urinary tract infections and intestinal infections, burns, boils,[7] poly-microbial biofilms on chronic wounds, ulcers and infected surgical sites. [cita requerida]

In 2007 a Phase 1/2 clinical trial was completed at the Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital, London for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections (otitis).[37][38][39] Documentation of the Phase-1/Phase-2 study was published in August 2009 in the journal Clinical Otolaryngology.[40]

Phase 1 clinical trials have now been completed in the Southwest Regional Wound Care Center, Lubbock, Texas for an approved cocktail of phages against bacteria, including P. aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli (better known as E. coli).[41] The cocktail of phages for the clinical trials was developed and supplied by Intralytix.

Reviews of phage therapy indicate that more clinical and microbiological research is needed to meet current standards.[42]

Administration[editar]

Phages can usually be freeze-dried and turned into pills without materially impacting efficiency.[7] Temperature stability up to 55 °C and shelf lives of 14 months have been shown for some types of phages in pill form.[7]

Application in liquid form is possible, stored preferably in refrigerated vials.[7]

Oral administration works better when an antacid is included, as this increases the number of phages surviving passage through the stomach.[7]

Topical administration often involves application to gauzes that are laid on the area to be treated.[7]

Obstacles[editar]

The high bacterial strain specificity of phage therapy may make it necessary for clinics to make different cocktails for treatment of the same infection or disease because the bacterial components of such diseases may differ from region to region or even person to person.

In addition, due to the specificity of individual phages, for a high chance of success, a mixture of phages is often applied. This means that 'banks' containing many different phages must be kept and regularly updated with new phages.[43]

Further, bacteria can evolve different receptors either before or during treatment; this can prevent the phages from completely eradicating the bacteria.[7]

The need for banks of phages makes regulatory testing for safety harder and more expensive under current rules in most countries. Such a process would make it difficult for large-scale production of phage therapy. Additionally, patent issues (specifically on living organisms) may complicate distribution for pharmaceutical companies wishing to have exclusive rights over their "invention", which would discourage for-profit corporation from investing capital in the dissemination of this technology.

As has been known for at least thirty years, mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis have specific bacteriophages.[44] No lytic phage has yet been discovered for Clostridium difficile, which is responsible for many nosocomial diseases, but some temperate phages (integrated in the genome, also called lysogenic) are known for this species; this opens encouraging avenues but with additional risks as discussed below.

To work the virus has to reach the site of the bacteria, and viruses can sometimes reach places antibiotics cannot. For example, jazz bassist Alfred Gertler got a bacterial infection in his bones after breaking an ankle. A physician in the U.S. told him that the foot must be amputated. He refused and was largely bed ridden for four years until phage therapy at the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia, eliminated the bacterial infection.[12] Then he had surgery to repair his ankle and resumed his career and family life.[45]

Funding for phage therapy research and clinical trials is generally insufficient and difficult to obtain, since it is a lengthy and complex process to patent bacteriophage products. Scientists comment that 'the biggest hurdle is regulatory', whereas an official view is that individual phages would need proof individually because it would be too complicated to do as a combination, with many variables. Due to the specificity of phages, phage therapy would be most effective with a cocktail injection, which is generally rejected by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Researchers and observers predict that for phage therapy to be successful the FDA must change its regulatory stance on combination drug cocktails.[43] Public awareness and education about phage therapy are generally limited to scientific or independent research rather than mainstream media.[46]

The negative public perception of viruses may also play a role in the reluctance to embrace phage therapy.[47]

Legislation[editar]

Approval of phage therapy for use in humans has not been given in Western countries with a few exceptions. Washington and Oregon law allows naturopathic physicians to use any therapy that is legal any place in the world on an experimental basis.[48]

In Texas phages are considered natural substances and can be used in addition to (but not as a replacement for) traditional therapy; they've been used routinely in a wound care clinic in Lubbock, TX, since 2006.[49]

In 2013 "the 20th biennial Evergreen International Phage Meeting ... conference drew 170 participants from 35 countries, including leaders of companies and institutes involved with human phage therapies from France, Australia, Georgia, Poland and the United States."[50]

Safety[editar]

Much of the difficulty in obtaining regulatory approval is proving safety for using a self-replicating entity which has the capability to evolve.[20]

As with antibiotic therapy and other methods of countering bacterial infections, endotoxins are released by the bacteria as they are destroyed within the patient (Herxheimer reaction). This can cause symptoms of fever; in extreme cases toxic shock (a problem also seen with antibiotics) is possible.[51] Janakiraman Ramachandran[52] argues that this complication can be avoided in those types of infection where this reaction is likely to occur by using genetically engineered bacteriophages which have had their gene responsible for producing endolysin removed. Without this gene the host bacterium still dies but remains intact because the lysis is disabled. On the other hand, this modification stops the exponential growth of phages, so one administered phage means one dead bacterial cell.[9] Eventually these dead cells are consumed by the normal house-cleaning duties of the phagocytes, which utilise enzymes to break down the whole bacterium and its contents into harmless proteins, polysaccharides and lipids.[53]

Temperate (or Lysogenic) bacteriophages are not generally used therapeutically, as this group can act as a way for bacteria to exchange DNA; this can help spread antibiotic resistance or even, theoretically, make the bacteria pathogenic (see Cholera). Carl Merril claimed that harmless strains of corynebacterium may have been converted into c. diphtheriae that "probably killed a third of all Europeans who came to North America in the seventeenth century".[54] Fortunately, many phages seem to be lytic only with negligible probability of becoming lysogenic.[55]

Efficacy[editar]

In Russia, mixed phage preparations may have a therapeutic efficacy of 50%. This equates to the complete cure of 50 of 100 patients with terminal antibiotic-resistant infection. The rate of only 50% is likely to be due to individual choices in admixtures and ineffective diagnosis of the causative agent of infection.[56]

Other animals[editar]

Brigham Young University is currently researching the use of phage therapy to treat American foulbrood in honeybees.[57][58]

Cultural impact[editar]

The 1925 novel and 1926 Pulitzer prize winner Arrowsmith used phage therapy as a plot point.[59][60][61]

Greg Bear's 2002 novel Vitals features phage therapy, based on Soviet research, used to transfer genetic material.

The 2012 collection of military history essays about the changing role of women in warfare, "Women in War - from home front to front line" includes a chapter featuring phage therapy: "Chapter 17: Women who thawed the Cold War".[62]

Notes[editar]

- ↑ Silent Killers: Fantastic Phages?, by David Kohn, CBS News: 48 Hours Mystery.

- ↑ McAuliffe et al. "The New Phage Biology: From Genomics to Applications" (introduction) in Mc Grath, S. and van Sinderen, D. (eds.) Bacteriophage: Genetics and Molecular Biology Caister Academic Press ISBN 978-1-904455-14-1

- ↑ "Phage Therapy: Concept to Cure". Frontiers in Microbiology 3. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00238. PMC 3400130. PMID 22833738.

- ↑ Aguita, Maria. «Combatting Bacterial Infection». LabNews.co.uk. Consultado el 5 de mayo de 2009.

- ↑ Pirisi A (2000). «Phage therapy—advantages over antibiotics?». Lancet 356 (9239): 1418. PMID 11052592. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74059-9.

- ↑ «Eaters of bacteria: Is phage therapy ready for the big time?». Discover Magazine. Consultado el 12 de abril de 2013.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i BBC Horizon: Phage — The Virus that Cures 1997-10-09

- ↑ Parfitt T (2005). «Georgia: an unlikely stronghold for bacteriophage therapy». Lancet 365 (9478): 2166-7. PMID 15986542. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66759-1.

- ↑ a b Thiel, Karl (January 2004). «Old dogma, new tricks—21st Century phage therapy». Nature Biotechnology (London UK: Nature Publishing Group) 22 (1): 31-36. PMID 14704699. doi:10.1038/nbt0104-31. Consultado el 15 de diciembre de 2007.

- ↑ http://www.iitd.pan.wroc.pl/en/clinphage2015

- ↑ «[Bacteriophages as antibacterial agents]». Harefuah (en hebrew) 143 (2): 121-5, 166. 2004. PMID 15143702. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ a b Häusler (2006, ch. 1, at the limits of medicine)

- ↑ Kuchment (2012, p. 11)

- ↑ Kutter, E; De Vos, D; Gvasalia, G; Alavidze, Z; Gogokhia, L; Kuhl, S; Abedon, ST (January 2010). «Phage therapy in clinical practice: treatment of human infections». Current pharmaceutical biotechnology 11 (1): 69-86. PMID 20214609. doi:10.2174/138920110790725401.

- ↑ Hanlon GW (2007). «Bacteriophages: an appraisal of their role in the treatment of bacterial infections». Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30 (2): 118-28. PMID 17566713. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.04.006.

- ↑ "Stalin's Forgotten Cure". Science, 25 October 2002 v.298

- ↑ Summers WC (2001). «Bacteriophage therapy». Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55: 437-51. PMID 11544363. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.437.

- ↑ Nina Chanishvili, 2009, "A Literature Review of the Practical Application of Bacteriophage Research", 184p.

- ↑ Kuchment, Anna (2011); Häusler, Thomas (2006)

- ↑ a b «KERA Think! Podcast: Viruses are Everywhere!». 16 de junio de 2011. Consultado el 4 de junio de 2012. (audio)

- ↑ a b Mc Grath S and van Sinderen D (editors). (2007). Bacteriophage: Genetics and Molecular Biology (1st edición). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-14-1. [1].

- ↑ Soothill JS (1994). «Bacteriophage prevents destruction of skin grafts by Pseudomonas aeruginosa». Burns 20 (3): 209-11. PMID 8054131. doi:10.1016/0305-4179(94)90184-8.

- ↑ «Phage therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a mouse burn wound model». Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51 (6): 1934-8. 2007. PMC 1891379. PMID 17387151. doi:10.1128/AAC.01028-06. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Targeted drug-carrying bacteriophages as antibacterial nanomedicines». Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51 (6): 2156-63. 2007. PMC 1891362. PMID 17404004. doi:10.1128/AAC.00163-07. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Targeting antibacterial agents by using drug-carrying filamentous bacteriophages». Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50 (6): 2087-97. 2006. PMC 1479106. PMID 16723570. doi:10.1128/AAC.00169-06. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Killing cancer cells by targeted drug-carrying phage nanomedicines». BMC Biotechnol. 8: 37. 2008. PMC 2323368. PMID 18387177. doi:10.1186/1472-6750-8-37. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/events/2015/05/event_detail_001155.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c3

- ↑ https://respond.niaid.nih.gov/conferences/bacteriophage/Pages/Agenda.aspx

- ↑ «Bacteriophage therapy for the treatment of infections». Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs (London, England : 2000) 10 (8): 766-74. August 2009. PMID 19649921. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «What is Phage Therapy?». phagetherapycenter.com. Consultado el 29 de noviembre de 2014.

- ↑ Abedon ST (2012). Salutary contributions of viruses to medicine and public health. In: Witzany G (ed). Viruses: Essential Agents of Life. Springer. 389-405. ISBN 978-94-007-4898-9.

- ↑ «Bacteriophages: potential treatment for bacterial infections». BioDrugs 16 (1): 57-62. 2002. PMID 11909002. doi:10.2165/00063030-200216010-00006. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ "Non-antibiotic therapies for infectious diseases." by Christine F Carson, and Thomas V Riley Communicable Diseases Intelligence Volume 27 Supplement, May 2003. Australian Dept of health website

- ↑ Scientists Engineer Viruses To Battle Bacteria : NPR

- ↑ «Bacteriophage endolysins as a novel class of antibacterial agents». Experimental Biology and Medicine (Maywood, N.J.) 231 (4): 366-77. April 2006. PMID 16565432. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Bogovazova, GG; Voroshilova, NN; Bondarenko, VM (1991). «The efficacy of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteriophage in the therapy of experimental Klebsiella infection». Zhurnal mikrobiologii, epidemiologii, i immunobiologii (4): 5-8. PMID 1882608.

- ↑ «Press & News». Consultado el 13 de diciembre de 2007.

- ↑ «biocontrol.ltd.uk». Consultado el 13 de diciembre de 2007.

- ↑ «biocontrol-ltd.com». Consultado el 30 de abril de 2008.

- ↑ Wright, A.; Hawkins, C.H.; Änggård, E.E.; Harper, D.R. (2009). «A controlled clinical trial of a therapeutic bacteriophage preparation in chronic otitis due to antibiotic-resistantPseudomonas aeruginosa; a preliminary report of efficacy». Clinical Otolaryngology 34 (4): 349-57. PMID 19673983. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01973.x.

- ↑ Rhoads DD, Wolcott RD, Kuskowski MA, Wolcott BM, Ward LS, Sulakvelidze A (2009). Bacteriophage therapy of venous leg ulcers in humans: results of a phase I safety trial. J Wound Care. 2009 Jun;18(6):237-8, 240-3.

- ↑ Brüssow, H (2005). «Phage therapy: The Escherichia coli experience». Microbiology (Reading, England) 151 (Pt 7): 2133-40. PMID 16000704. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27849-0.

- ↑ a b Keen, E. C. (2012). «Phage Therapy: Concept to Cure». Frontiers in Microbiology 3: 238. PMC 3400130. PMID 22833738. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00238.

- ↑ Graham F. HATFULL 12 - Mycobacteriophages : Pathogenesis and Applications, pages 238-255 (in Waldor, M.K., D.I. Friedman, and S.L. Adhya, Phages: Their role in bacterial pathogenesis and biotechnology, 2005, University of Michigan; Sankar L. Adhya, National Institutes of Health: ASM Press).

- ↑ Kutter, Betty (c. 2009), Our First Adventure With Phage Therapy: Alfred's Story, Olympia, WA: Evergreen College, consultado el 27 de abril de 2015.

- ↑ Brüssow, H 2007. Phage Therapy: The Western Perspective. in S. McGrath and D. van Sinderen (eds.) Bacteriophage: Genetics and Molecular Biology, Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, UK. ISBN 978-1-904455-14-1

- ↑ «European regulatory conundrum of phage therapy». Future Microbiol 2 (5): 485-91. 2007. PMID 17927471. doi:10.2217/17460913.2.5.485. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Faltys, Doris (4 August 2013), «Evergreen Researcher Dr. Kutter Announces 'There's a Phage for That'», Thurston Talk (Olympia, Washington), consultado el 1 de marzo de 2015.

- ↑ Kuchment (2011, ch. 12, pp. 115-118): In addition to mentioning that Texas law allows physicians to use "natural substances" like phages in addition to (but not in lieu of) standard medical practice, Kuichment says, "In June 2009 [Dr. Randall Wolcott's] study was published in the Journal of Wound Care."

- ↑ December 2013 Faculty Spotlight, Olympia, WA: Evergreen College, December 2013, consultado el 1 de marzo de 2015.

- ↑ Evergreen PHAGE THERAPY: BACTERIOPHAGES AS ANTIBIOTICS

- ↑ Stone, Richard. "Stalin's Forgotten Cure." Science Online 282 (25 October 2002).

- ↑ Fox, Stuart Ira (1999). Human Physiology -6th ed.. McGraw-Hill. pp. : 50,55,448,449. ISBN 0-697-34191-7.

- ↑ Kuchement (2011, p. 94)

- ↑ Kuchement (2011, ch. 6, p. 63): "[T]he Hirszfeld Institute [in Poland] has almost always done its research studies in the absence of double-bind controls ... . But the sheer quantity of cases, combined with the fact that nearly all the cases involve patients who failed to respond to antibiotics, is persuasive."

- ↑ В.Н.Крылов (5 April 2007). «фаготерапия». Consultado el 29 de noviembre de 2014.

- ↑ «Bee Killers: Using Phages Against Deadly Honeybee Diseases». youtube.com. Consultado el 29 de noviembre de 2014.

- ↑ «Using microscopic bugs to save the bees». news.byu.edu. Consultado el 1 de diciembre de 2014.

- ↑ Summers WC (1991). «On the origins of the science in Arrowsmith: Paul de Kruif, Felix d'Herelle, and phage». J Hist Med Allied Sci 46 (3): 315-32. PMID 1918921. doi:10.1093/jhmas/46.3.315.

- ↑ «Phage Findings». Time. 3 de enero de 1938. Consultado el 13 de diciembre de 2007.

- ↑ «SparkNotes: Arrowsmith: Chapters 31–33». Consultado el 13 de diciembre de 2007.

- ↑ http://www.winstonchurchill.org/publications/chartwell-bulletin/bulletin-48-jun-2012/churchill-the-wartime-feminist

<ref> definida en las <references> con nombre «pmid17958494» no se utiliza en el texto anterior.References[editar]

- Kuchment, Anna (2011), The Forgotten Cure: The Past and Future of Phage Therapy, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4614-0250-3.

- Häusler, Thomas (2006), Virus vs. Superbug: A solution to the antibiotic crisis?, Macmillan, p. 48, ISBN 978-0-230-55193-0.

External links[editar]

- Thiel, Karl (2004). «Old dogma, new tricks—21st Century phage therapy». Nature Biotechnology 22 (1): 31-6. PMID 14704699. doi:10.1038/nbt0104-31.

- Popsci: The Next Phage

- Bacteriophage (Journal)

- Elkadi, Omar Anwar (2014). «Phage therapy: The new old antibacterial therapy». El Mednifico Journal 2 (3): 311. doi:10.18035/emj.v2i3.202.