Alfabeto mongol tradicional

| Alfabeto mongol clásico | ||

|---|---|---|

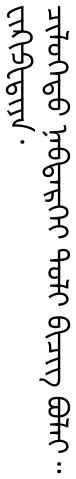

Muestra del texto en la escritura tradicional mongola | ||

| Tipo | alfabeto | |

| Idiomas | idioma mongol | |

| Creador | Tata Tonga | |

| Época | siglo XIII-actualidad | |

| Estado |

inactivo en Mongolia activo en Mongolia Interior | |

| Antecesores |

alfabeto sogdiano

| |

| Dirección | vertical left-to-right y dextroverso | |

| Letras | ᠡ | |

| Unicode | Mongolian | |

| ISO 15924 |

Mong, 145 | |

El alfabeto mongol tradicional o clásico (o simplemente alfabeto mongol o escritura mongola; en mongol: ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ Mongγol bičig, en alfabeto moderno (cirílico): Монгол бичиг Mongol bichig, también llamado Hudum Mongol bichig) fue el primer sistema de escritura (concretamente alfabeto) creado para escribir el idioma mongol . También ha sido adaptado para escribir otros idiomas, como el idioma manchú. En Mongolia se hizo un intento de reemplazarlo en 1931 por alfabeto latino, poco después, en 1946 fue abandonado por completo a favor del alfabeto cirílico. En Mongolia Interior, República Popular China sigue activo. Actualmente el gobierno mongol está implementando un plan para ir reemplazando el alfabeto cirílico por el mongol tradicional.

Nombre

Debido a que fue desarrollado a partir del alfabeto uigur se le llama también escritura uigur mongola (en mongol: Уйгуржин монгол бичиг Uygurjin mongol bichig). Durante la época comunista con introducir el alfabeto cirílico se empezó a denominarlo antiguo alfabeto mongol (Хуучин монгол бичиг Huuchin mongol bichig).

Historia

El alfabeto vertical mongol se desarrolló del alfabeto sogdiano como su adaptación al idioma mongol. Desde el siglo VII-VIII hasta el siglo XV-XVI, el mongol se estaba diferenciando en dialectos: sureño, oriental y occidental. Las principales muestras de la etapa media del desarrollo del dialecto oriental son: la Historia secreta de los mongoles, textos escritos en la escritura cuadrada, diccionarios mongolo-chinos del siglo XIV y transcripciones chinas del idioma mongol. Las muestras del dialecto occidental son: diccionarios árabe-mongoles y persa-mongoles, textos mongoles en la transcripción árabe, entre otras.

Las principales características de la etapa media son las siguientes: las vocales "i", "ï" dejaron de sonar diferente; desaparecieron las consonantes γ/g y b/w; empezaron a formarse las vocales largas; existencia de la "h" inicial; parcial ausencia de las categorías gramaticales, entre otras. Esta etapa del desarrollo del idioma mongol explica su parentesco con la escritura árabe, con la diferencia del sentido de escribir (el árabe se escribe desde la derecha hacia la izquierda y el mongol tradicional se escribe desde arriba hacia abajo).[1]

Enseñanza

Los mongoles aprendían su alfabeto como si se tratase de un silabario, dividiendo las sílabas (todas acabadas con una vocal) en doce clases, basándose en el último fonema de cada sílaba.[2] Los manchúes aprendían su alfabeto también como un silabario, también dividiendo las sílabas en doce categorías diferentes basándose en su último fonema.[3][4][5]

A pesar de que su escritura fue un alfabeto, los niños manchúes no lo aprendían letra tras letra, como en el occidente ("l" + "a" = "la"; "l" + "o" = "lo"), sino memorizaban cada sílaba aparte y las escribían como la escritura china ("la"; "lo").[6]

Hoy en día, la opinión sobre la naturaleza de la escritura tradicional mongola está dividida. Los expertos en China la consideran silabario y en la enseñanza sigue usándose el sistema de los manchúes, mientras que por los occidentales que estudian el idioma y la escritura mongola lo consideran un alfabeto, y lo aprenden como tal. Estudiar la escritura mongola tratándola como silabario lleva más tiempo.[7][8]

Actualmente el gobierno de Mongolia trabaja en un plan de recuperación del alfabeto mongol tradicional, de acuerdo a una ley aprobada en 2015, se espera que para 2025, el alfabeto mongol y el cirílico serán de uso oficial, sin embargo en 2030 solo será de uso oficial el alfabeto mongol tradicional, terminando así con el alfabeto cirílico impuesto por la Unión Soviética a Mongolia desde 1946.[9]

Letras

| Caracteres[10] | Transliteración | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| inicial | central | final | Latino[11] | Cirílico | |

| a | А | ||||

| e | Э | ||||

| i, yi | И, Й, Ы, Ь | ||||

| o, u | О, У | ||||

| ö, ü | Ө, Ү | ||||

| n | Н | ||||

| ng | Н, НГ | ||||

| b | Б, В | ||||

| p | П | ||||

| q | Х | ||||

| ɣ | Г | ||||

| k | Х | ||||

| g | Г | ||||

| m | М | ||||

| l | Л | ||||

| s | С | ||||

| š | Ш | ||||

| t, d | Т, Д | ||||

| č | Ч, Ц | ||||

| ǰ | Ж, З | ||||

| y | *-Й, Е*, Ё*, Ю*, Я* | ||||

| r | Р | ||||

| v | В | ||||

| f | Ф | ||||

| ḳ | К | ||||

| (c) | (ц) | ||||

| (z) | (з) | ||||

| (h) | (г, х) | ||||

Ejemplos

| A mano | Tinta | Unicode |

|---|---|---|

|

|

ᠸᠢᠺᠢᠫᠧᠳᠢᠶᠠ᠂ᠴᠢᠯᠦᠭᠡᠲᠦ ᠨᠡᠪᠲᠡᠷᠬᠡᠢ ᠲᠣᠯᠢ ᠪᠢᠴᠢᠭ ᠪᠣᠯᠠᠢ |

- Transliteración: Vikipediya čilügetü nebterkei toli bičig bolai.

- Cirílico: Википедиа чөлөөт нэвтэрхий толь бичиг болой.

- Transcripción del cirílico: Vikipedia chölööt nevterkhii toli bichig boloi.

- Análisis: Wikipedia libre todo-profundo escritura es.

- Traducción: Wikipedia es la enciclopedia libre.

Unicode

El alfabeto mongol tradicional fue añadido al sistema Unicode en septiembre de 1999, en su versión 3.0.[12]

| 1800 ᠀ Birga

|

1801 ᠁ Ellipsis

|

1802 ᠂ Comma

|

1803 ᠃ Full Stop

|

1804 ᠄ Colon

|

1805 ᠅ Four Dots

|

1806 ᠆ Todo Soft Hyphen

|

1807 ᠇ Sibe Syllable Boundary Marker

|

1808 ᠈ Manchu Comma

|

1809 ᠉ Manchu Full Stop

|

180A ᠊ Nirugu

|

180B ᠋ Free Variation Selector One

|

180C ᠌ Free Variation Selector Two

|

180D ᠍ Free Variation Selector Three

|

180E Vowel Separator

|

|

| 1810 ᠐ Zero

|

1811 ᠑ One

|

1812 ᠒ Two

|

1813 ᠓ Three

|

1814 ᠔ Four

|

1815 ᠕ Five

|

1816 ᠖ Six

|

1817 ᠗ Seven

|

1818 ᠘ Eight

|

1819 ᠙ Nine

|

||||||

| 1820 ᠠ A

|

1821 ᠡ E

|

1822 ᠢ I

|

1823 ᠣ O

|

1824 ᠤ U

|

1825 ᠥ Oe

|

1826 ᠦ Ue

|

1827 ᠧ Ee

|

1828 ᠨ Na

|

1829 ᠩ Ang

|

182A ᠪ Ba

|

182B ᠫ Pa

|

182C ᠬ Qa

|

182D ᠭ Ga

|

182E ᠮ Ma

|

182F ᠯ La

|

| 1830 ᠰ Sa

|

1831 ᠱ Sha

|

1832 ᠲ Ta

|

1833 ᠳ Da

|

1834 ᠴ Cha

|

1835 ᠵ Ja

|

1836 ᠶ Ya

|

1837 ᠷ Ra

|

1838 ᠸ Wa

|

1839 ᠹ Fa

|

183A ᠺ Ka

|

183B ᠻ Kha

|

183C ᠼ Tsa

|

183D ᠽ Za

|

183E ᠾ Haa

|

183F ᠿ Zra

|

| 1840 ᡀ Lha

|

1841 ᡁ Zhi

|

1842 ᡂ Chi

|

1843 ᡃ Todo Long Vowel Sign

|

1844 ᡄ Todo E

|

1845 ᡅ Todo I

|

1846 ᡆ Todo O

|

1847 ᡇ Todo U

|

1848 ᡈ Todo Oe

|

1849 ᡉ Todo Ue

|

184A ᡊ Todo Ang

|

184B ᡋ Todo Ba

|

184C ᡌ Todo Pa

|

184D ᡍ Todo Qa

|

184E ᡎ Todo Ga

|

184F ᡏ Todo Ma

|

| 1850 ᡐ Todo Ta

|

1851 ᡑ Todo Da

|

1852 ᡒ Todo Cha

|

1853 ᡓ Todo Ja

|

1854 ᡔ Todo Tsa

|

1855 ᡕ Todo Ya

|

1856 ᡖ Todo Wa

|

1857 ᡗ Todo Ka

|

1858 ᡘ Todo Gaa

|

1859 ᡙ Todo Haa

|

185A ᡚ Todo Jia

|

185B ᡛ Todo Nia

|

185C ᡜ Todo Dza

|

185D ᡝ Sibe E

|

185E ᡞ Sibe I

|

185F ᡟ Sibe Iy

|

| 1860 ᡠ Sibe Ue

|

1861 ᡡ Sibe U

|

1862 ᡢ Sibe Ang

|

1863 ᡣ Sibe Ka

|

1864 ᡤ Sibe Ga

|

1865 ᡥ Sibe Ha

|

1866 ᡦ Sibe Pa

|

1867 ᡧ Sibe Sha

|

1868 ᡨ Sibe Ta

|

1869 ᡩ Sibe Da

|

186A ᡪ Sibe Ja

|

186B ᡫ Sibe Fa

|

186C ᡬ Sibe Gaa

|

186D ᡭ Sibe Haa

|

186E ᡮ Sibe Tsa

|

186F ᡯ Sibe Za

|

| 1870 ᡰ Sibe Raa

|

1871 ᡱ Sibe Cha

|

1872 ᡲ Sibe Zha

|

1873 ᡳ Manchu I

|

1874 ᡴ Manchu Ka

|

1875 ᡵ Manchu Ra

|

1876 ᡶ Manchu Fa

|

1877 ᡷ Manchu Zha

|

||||||||

| 1880 ᢀ Ali Gali Anusvara One

|

1881 ᢁ Ali Gali Visarga One

|

1882 ᢂ Ali Gali Damaru

|

1883 ᢃ Ali Gali Ubadama

|

1884 ᢄ Ali Gali Inverted Ubadama

|

1885 ᢅ Ali Gali Baluda

|

1886 ᢆ Ali Gali Three Baluda

|

1887 ᢇ Ali Gali A

|

1888 ᢈ Ali Gali I

|

1889 ᢉ Ali Gali Ka

|

188A ᢊ Ali Gali Nga

|

188B ᢋ Ali Gali Ca

|

188C ᢌ Ali Gali Tta

|

188D ᢍ Ali Gali Ttha

|

188E ᢎ Ali Gali Dda

|

188F ᢏ Ali Gali Nna

|

| 1890 ᢐ Ali Gali Ta

|

1891 ᢑ Ali Gali Da

|

1892 ᢒ Ali Gali Pa

|

1893 ᢓ Ali Gali Pha

|

1894 ᢔ Ali Gali Ssa

|

1895 ᢕ Ali Gali Zha

|

1896 ᢖ Ali Gali Za

|

1897 ᢗ Ali Gali Ah

|

1898 ᢘ Todo Ali Gali Ta

|

1899 ᢙ Todo Ali Gali Zha

|

189A ᢚ Manchu Ali Gali Gha

|

189B ᢛ Manchu Ali Gali Nga

|

189C ᢜ Manchu Ali Gali Ca

|

189D ᢝ Manchu Ali Gali Jha

|

189E ᢞ Manchu Ali Gali Tta

|

189F ᢟ Manchu Ali Gali Ddha

|

| 18A0 ᢠ Manchu Ali Gali Ta

|

18A1 ᢡ Manchu Ali Gali Dha

|

18A2 ᢢ Manchu Ali Gali Ssa

|

18A3 ᢣ Manchu Ali Gali Cya

|

18A4 ᢤ Manchu Ali Gali Zha

|

18A5 ᢥ Manchu Ali Gali Za

|

18A6 ᢦ Ali Gali Half U

|

18A7 ᢧ Ali Gali Half Ya

|

18A8 ᢨ Manchu Ali Gali Bha

|

18A9 ᢩ Ali Gali Dagalga

|

18AA ᢪ Manchu Ali Gali Lha

|

|||||

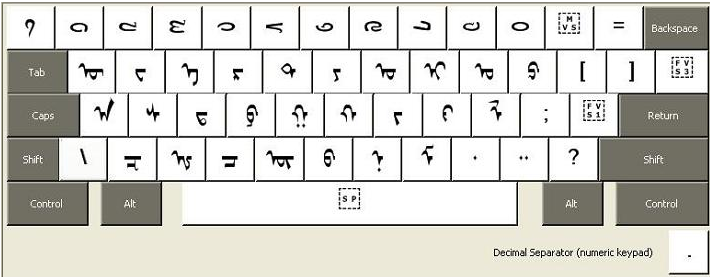

Teclado

Véase también

Enlaces externos

- Presentación del alfabeto en Omniglot.com

- Muestras de escritura con audios

- Making Sense of the Traditional Mongolian Script, artículo donde se explica más el alfabeto

- Herramienta para transcribir textos al alfabeto tradicional en línea

Referencias

- ↑ György Kara, "Aramaic Scripts for Altaic Languages", en: Daniels & Bright The World's Writing Systems, 1994.

- ↑ Chinggeltei. (1963) A Grammar of the Mongol Language. Nueva York, Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. pág. 15.

- ↑ Translation of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese Grammar of the Manchu Tartar Language; with introductory notes on Manchu Literature: (translated by A. Wylie.). Mission Press. 1855. pp. xxvii-.

- ↑ Shou-p'ing Wu Ko (1855). Translation (by A. Wylie) of the Ts'ing wan k'e mung, a Chinese grammar of the Manchu Tartar language (by Woo Kĭh Show-ping, revised and ed. by Ching Ming-yuen Pei-ho) with intr. notes on Manchu literature. pp. xxvii-.

- ↑ «DAHAI». web.archive.org. Archivado desde el original el 10 de junio de 2016. Consultado el 30 de mayo de 2021. «DAHAI 達海, d. 1632, age 38 (sui), of the Plain Blue Banner, belonged to a family that had long been settled in Giolca, home of Desiku (see under Anfiyanggû), the granduncle of Nurhaci [q. v.]. His grandfather and his father early entered the service of Nurhaci where Dahai had opportunity to learn Chinese as well as Manchu. He devoted himself to study, and after he came of age was put in charge of written communications with the Ming government and with Korea, involving the preparation of Chinese texts. His knowledge of the Chinese language was so valuable that when condemned to death in 1620, for being intimate with and receiving presents from a maid-servant, he was reprieved by Nurhaci on the ground that he could not be spared. Nurhaci commissioned him to translate into Manchu, in the system of writing developed by Erdeni [q. v.] and others, the sections relating to the penal code in the 大明會典 Ta Ming hui-tien and two works on military science-the 素書 Su-shu (an edition of 1704 is extant) and the 三略 San-lüeh. When the Wên Kuan, or Literary Office, was established under Nurhaci's successor (see under Abahai) Dahai was appointed with four others to continue the translation of Chinese works. In 1629 and 1630, when the Manchu attack penetrated the Great Wall and reached the gates of Peking (see under Man Kuei), he was responsible for the proclamations and messages in the Chinese language. On the completion of some of his translations in 1630 he was given a hereditary rank, being the first of the non-military officials ever to be so honored. In the following language, classifying the words according to Mongol practice under twelve types of opening year he was given the title, baksi, or "teacher".»

- ↑ Saarela 2014, p. 169.

- ↑ Gertraude Roth Li (2000). Manchu: a textbook for reading documents. University of Hawaii Press. p. 16. ISBN 0824822064. Consultado el 25 de marzo de 2012. «Alphabet: Some scholars consider the Manchu script to be a syllabic one.»

- ↑ Gertraude Roth Li (2010). Manchu: A Textbook for Reading Documents (Second Edition) (2 edición). Natl Foreign Lg Resource Ctr. p. 16. ISBN 0980045959. Consultado el 1 de marzo de 2012. «Alphabet: Some scholars consider the Manchu script to be a syllabic one. Others see it as having an alphabet with individual letters, some of which differ according to their position within a word. Thus, whereas Denis Sinor aruged in favor of a syllabic theory,30 Louis Ligeti preferred to consider the Manchu script and alphabetical one.31».()

- ↑ «Mongolia recobra alfabeto mongol después de abandonar el cirilico». www.eldiario.es. Consultado el 17 de mayo de 2020.

- ↑ «Mongolian alphabets, pronunciation and language». www.omniglot.com. Consultado el 7 de febrero de 2017.

- ↑ Poppe, Nicolas Grammar of Written Mongolian 3rd ed. University of Washington, 1974.

- ↑ Official Unicode Consortium code chart