Diferencia entre revisiones de «Camuflaje disruptivo»

Se traduce desde wiki en |

(Sin diferencias)

|

Revisión del 12:17 14 dic 2018

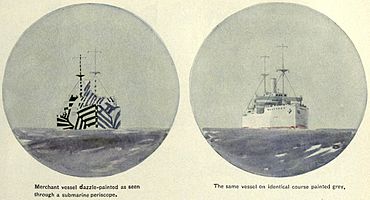

El camuflaje con distorsión o camuflaje deslumbrante (del inglés dazze camouflage), fue una familia de camuflaje de barcos que se usó ampliamente en la Primera Guerra Mundial y, en menor medida, en la [[Segunda Guerra Mundial y posteriores. Acreditado con el artista marino británico Norman Wilkinson, consistía en complejos patrones de formas geométricas en colores contrastantes, que se interrumpen y se cruzan entre sí.

A diferencia de otras formas de camuflaje, la intención de la distorsión visual no es ocultar, sino dificultar la estimación del alcance, la velocidad y el rumbo de un objetivo. Norman Wilkinson explicó en 1919 que había tenido la intención de confundir principalmente para engañar al enemigo sobre el rumbo de un barco y así asumir una posición de disparo deficiente. [3]

Este tipo de camuflaje fue adoptado por el Almirantazgo en el Reino Unido y luego por la [{Marina de los Estados Unidos]]. El patrón de pintura de cada nave era único para evitar que las clases de naves fueran reconocidas instantáneamente por el enemigo. El resultado fue que se probó una profusión de esquemas distorsivos, y la evidencia de su éxito fue, en el mejor de los casos, mixta. Tantos factores estaban involucrados que era imposible determinar cuáles eran importantes y si alguno de los esquemas de color era efectivo.

Este tipo de diseños atrajo la atención de artistas como Picasso, quienes afirmaron que los cubistas como él lo habían inventado.[4] Edward Wadsworth, quien supervisó el camuflaje de más de 2,000 barcos durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, pintó una serie de lienzos de barcos con camuflaje por distorsión [5][6][7][8][9] después de la guerra, en base a su trabajo de guerra. Arthur Lismer pintó de manera similar una lienzos de barcos con camuflaje por distorsión.

Bibliografía

- Behrens, Roy R., ed. (2012). Ship Shape: A Dazzle Camouflage Sourcebook. Bobolink Books. ISBN 978-0-9713244-7-3.

Enlaces externos

Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Camuflaje disruptivo.

Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Camuflaje disruptivo.- Newly discovered dazzle plans at Rhode Island School of Design

- El desarrollo del camuflaje naval 1914–1945

- Contribuciones de artistas al camuflaje en el siglo XX

- Camoupedia: dazzle camouflage

- Razzle dazzle camouflage

- "She's All Dressed Up For Peace", Popular Science (Febrero 1919), p. 55.

- "Fighting the U-Boat with Paint", Popular Science (Abril 1919), pp. 17–19.

- Destroyer Escort Historical Museum: USS Slater painted in 1945 Dazzle camouflage

- US Navy PT Boats in Dazzle Camouflage

- Catalogue of US Navy World War II ships in Dazzle Camouflage

Notas

- ↑ Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; no se ha definido el contenido de las referencias llamadasNewark74 - ↑ Wilkinson, Norman (1969). A Brush with Life. Seeley Service. p. 79.

- ↑ Wilkinson said "The primary object of this scheme was not so much to cause the enemy to miss his shot when actually in firing position, but to mislead him, when the ship was first sighted, as to the correct position to take up. Dazzle was a method to produce an effect by paint in such a way that all accepted forms of a ship are broken up by masses of strongly contrasted colour, consequently making it a matter of difficulty for a submarine to decide on the exact course of the vessel to be attacked." For example, an enemy submarine might position itself poorly, leaving itself at long range or out of range altogether.[1] Wilkinson further wrote that dazzle was designed "not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading".[2]

- ↑ Campbell-Johnson, Rachel (21 March 2007). «Camouflage at IWM». The Times.

- ↑ For example, Wadsworth's Dazzle-ships in Drydock at Liverpool, 1919.

- ↑ Marter, Joan M. The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, Oxford University Press, 2011, vol. 1, p. 401.

- ↑ Saunders, Nicholas J.; Cornish, Paul. (eds). Contested Objects: Material Memories of the Great War, Routledge, 2014. Jonathan Black: "'A few broad stripes': Perception, Deception, and the 'Dazzle Ship' phenomenon of the First World War.", pp. 190–202.

- ↑ Newbolt, Sir Henry John Newbolt. Submarine and Anti-Submarine, Longmans, Green and Co, 1919. p. 46. "You look long and hard at this dazzle-ship. She doesn't give you any sensation of being dazzled; but she is, in some queer way, all wrong".

- ↑ Deer, Patrick. Culture in Camouflage: War, Empire, and Modern British Literature. Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 46.

Referencias

Bibliografía

- Forbes, Peter (2009). Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17896-8.

- Williams, David. (2001). Naval camouflage, 1914–1945: a complete visual reference. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-496-8.

marine artist and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve officer Norman Wilkinson, agreed with Kerr that dazzle's aim was confusion rather than concealment, but disagreed about the type of confusion to be sown in the enemy's mind. What Wilkinson wanted to do was to make it difficult for an enemy to estimate a ship's type, size, speed, and heading, and thereby confuse enemy ship commanders into taking mistaken or poor firing positions.[1][2] An observer would find it difficult to know exactly whether the stern or the bow was in view; and it would be correspondingly difficult to estimate whether the observed vessel was moving towards or away from the observer's position.[3]

Wilkinson advocated "masses of strongly contrasted colour" to confuse the enemy about a ship's heading.[4][1] Thus, while dazzle, in some lighting conditions or at close ranges, might actually increase a ship's visibility,[5] the conspicuous patterns would obscure the outlines of the ship's hull (though admittedly not the superstructure[6]), disguising the ship's correct heading and making it harder to hit.[7]

Dazzle was created in response to an extreme need, and hosted by an organisation, the Admiralty, which had already rejected an approach supported by scientific theory: Kerr's proposal to use "parti-colouring" based on the known camouflage methods of disruptive coloration and countershading. This was dropped in favour of an admittedly non-scientific approach, led by the socially well-connected Wilkinson.[8] Kerr's explanations of the principles were clear, logical, and based on years of study, while Wilkinson's were simple and inspirational, based on an artist's perception.[5] The decision was likely because the Admiralty felt comfortable with Wilkinson, in sharp contrast to their awkward relationship with the stubborn and pedantic Kerr.[8][9]

Wilkinson claimed not to have known of the zoological theories of camouflage of Kerr and Thayer, admitting only to having heard of the "old invisibility-idea" from Roman times.[5][11]

Possible mechanisms

Disrupting rangefinding

In 1973, the naval museum curator Robert F. Sumrall[12] (following Kerr[13]) suggested a mechanism by which dazzle camouflage may have sown the kind of confusion that Wilkinson had intended for it. Coincidence rangefinders used for naval artillery had an optical mechanism, operated by a human to compute the range. The operator adjusted the mechanism until the two half-images of the target lined up in a complete picture. Dazzle, Sumrall argued, was intended to make that hard, as clashing patterns looked abnormal even when the two halves were aligned, something that became more important when submarine periscopes included such rangefinders. Patterns sometimes also included a false bow wave to make it difficult for an enemy to estimate the ship's speed.[14]

Disguising heading and speed

The historian Sam Willis argued that since Wilkinson knew it was impossible to make a ship invisible with paint, the "extreme opposite"[15] was the answer, using conspicuous shapes and violent colour contrasts to confuse enemy submarine commanders. Willis pointed out, using the Plantilla:HMT dazzle scheme as an example, that different mechanisms could have been at work. The contradictory patterns on the ship's funnels could imply the ship was on a different heading (as Wilkinson had said[1]). The curve on the hull below the front funnel could seem to be a false bow wave, creating a misleading impression of the ship's speed. And the striped patterns at bow and stern could create confusion about which end of the ship was which.[15]

That dazzle did indeed work along these lines is suggested by the testimony of a U-boat captain:[1]

It was not until she was within half a mile that I could make out she was one ship [not several] steering a course at right angles, crossing from starboard to port. The dark painted stripes on her after part made her stern appear her bow, and a broad cut of green paint amidships looks like a patch of water. The weather was bright and visibility good; this was the best camouflage I have ever seen.[1]

Motion dazzle

In 2011, the scientist Nicholas E. Scott-Samuel and colleagues presented evidence using moving patterns on a computer that human perception of speed is distorted by dazzle patterns. However, the speeds required for motion dazzle are much larger than were available to First World War ships: Scott-Samuel notes that the targets in the experiment would correspond to a dazzle-patterned Land Rover vehicle at a range of 70 m (76,6 yd), travelling at 90 km/h (55,9 mph). If such a dazzling target causes a 7% confusion in the observed speed, a rocket propelled grenade travelling that distance in half a second would strike 90 cm (35,4 plg) from the intended aiming point, or 7% of the distance moved by the target. This might be enough to save lives in the dazzle-patterned vehicle, and perhaps to cause the missile to miss entirely.[16][17]

World War I

In 1914, Kerr persuaded the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, to adopt a form of military camouflage which he called "parti-colouring". He argued both for countershading (following the American artist Abbott Thayer), and for disruptive coloration, both as used by animals.[18] A general order to the British fleet issued on 10 November 1914 advocated use of Kerr's approach. It was applied in various ways to British warships such as HMS Implacable, where officers noted approvingly that the pattern "increased difficulty of accurate range finding". However, following Churchill's departure from the Admiralty, the Royal Navy reverted to plain grey paint schemes,[19] informing Kerr in July 1915 that "various trials had been undertaken and that the range of conditions of light and surroundings rendered it necessary to modify considerably any theory based upon the analogy of [the colours and patterns of] animals".[20]

The British Army inaugurated its Camouflage Section for land use at the end of 1916. At sea in 1917, heavy losses of merchant ships to Germany's unrestricted submarine warfare campaign led to new desire for camouflage. The marine painter Norman Wilkinson promoted a system of stripes and broken lines "to distort the external shape by violent colour contrasts" and confuse the enemy about the speed and dimensions of a ship.[21] Wilkinson, then a lieutenant commander on Royal Navy patrol duty, implemented the precursor of "dazzle" beginning with the merchantman SS Industry. Wilkinson was put in charge of a camouflage unit which used the technique on large groups of merchant ships. Over 4000 British merchant ships were painted in what came to be known as "dazzle camouflage"; dazzle was also applied to some 400 naval vessels, starting in August 1917.[19][23]

All British patterns were different, first tested on small wooden models viewed through a periscope in a studio. Most of the model designs were painted by women from London's Royal Academy of Arts. A foreman then scaled up their designs for the real thing. Painters, however, were not alone in the project. Creative people including sculptors, artists, and set designers designed camouflage.[24]

Wilkinson's Dazzle camouflage was accepted by the Admiralty, even without practical visual assessment protocols for improving performance by modifying designs and colours.[25] The dazzle camouflage strategy was adopted by other navies. This led to more scientific studies of colour options which might enhance camouflage effectiveness.[26]

After the war, starting on 27 October 1919, an Admiralty committee met to determine who had priority for the invention of dazzle. Kerr was asked whether he thought Wilkinson had personally benefited from anything he Kerr had written. Kerr avoided the question, implying that he had not, and said "I make no claim to have invented the principle of parti-colouring, this principle was, of course, invented by nature".[8] He agreed also that he had not suggested anywhere in his letters that his system would "create an illusion as to the course of the vessel painted".[8] In October 1920 the Admiralty told Kerr that he was not seen as responsible for dazzle painting.[8] In 1922 Wilkinson was awarded the sum of £2000 for the invention.[8]

Effectiveness

Dazzle's effectiveness was highly uncertain at the time of the First World War, but it was nonetheless adopted both in the UK and North America. In 1918, the Admiralty analysed shipping losses, but was unable to draw clear conclusions. Dazzle ships were attacked in 1.47% of sailings, compared to 1.12% for uncamouflaged ships, suggesting increased visibility, but as Wilkinson had argued, dazzle was not attempting to make ships hard to see. Suggestively, of the ships that were struck by torpedoes, 43% of the dazzle ships sank, compared to 54% of the uncamouflaged; and similarly, 41% of the dazzle ships were struck amidships, compared to 52% of the uncamouflaged. These comparisons could be taken to imply that submarine commanders did have more difficulty in deciding where a ship was heading and where to aim. However, the ships painted in dazzle were larger than the uncamouflaged ships, 38% of them being over 5000 tons compared to only 13% of uncamouflaged ships, making comparisons unreliable.[7][27]

With hindsight, too many factors (choice of colour scheme; size and speed of ships; tactics used) had been varied for it to be possible to determine which factors were significant or which schemes worked best.[28] Thayer did carry out an experiment on dazzle camouflage, but it failed to show any reliable advantage over plain paintwork.[29]

The American data were analysed by Harold Van Buskirk in 1919. About 1,256 ships were painted in dazzle between 1 March 1918 and the end of the war on 11 November that year. Among American merchantmen 2,500 tons and over, 78 uncamouflaged ships were sunk, and only 18 camouflaged ships; out of these 18, 11 were sunk by torpedoes, 4 in collisions and 3 by mines. No US Navy ships (all camouflaged) were sunk in the period.[30][31]

World War II

However effective dazzle camouflage may have been in World War I, it became less useful as rangefinders and especially aircraft became more advanced, and, by the time it was put to use again in World War II, radar further reduced its effectiveness. However, it may still have confounded enemy submarines.[32]

In the Royal Navy, dazzle paint schemes reappeared in January 1940. These were unofficial, and competitions were often held between ships for the best camouflage patterns. The Royal Navy's Camouflage Department came up with a scheme devised by a young naval officer, Peter Scott, a wildlife artist, which were developed into the Western Approaches Schemes. In 1942 the Admiralty Intermediate Disruptive Pattern came into use, followed in 1944 by the Admiralty Standard Schemes.[33]

The United States Navy implemented a camouflage painting program in World War II, and applied it to many ship classes, from patrol craft and auxiliaries to battleships and some Plantilla:Sclass-s. The designs (known as Measures, each identified with a number) were not arbitrary, but were standardised in a process which involved a planning stage, then a review, and then fleet-wide implementation.[32] Not all United States Navy measures involved dazzle patterns; some were simple or even totally unsophisticated, such as a false bow wave on traditional Haze Gray, or Deck Blue replacing grey over part or all of the ship (the latter to counter the kamikaze threat).[34] Dazzle measures were used until 1945; in February 1945 the United States Navy's Pacific Fleet decided to repaint its ships in non-dazzle measures against the kamikaze threat, while the Atlantic Fleet continued to use dazzle, ships being repainted if transferred to the Pacific.[35]

Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine first used camouflage in the 1940 Norwegian campaign. A wide range of patterns were authorised, but most commonly black and white diagonal stripes were used. Most patterns were designed to hide ships in harbour or near the coast; they were often painted over with plain grey when operating in the Atlantic.[36][37]

Arts

The abstract patterns in dazzle camouflage inspired artists including Picasso. With characteristic hyperbole,[38] he claimed credit for camouflage experiments, which seemed to him a quintessentially Cubist technique.[39] In a conversation with Gertrude Stein shortly after he first saw a painted cannon trundling through the streets of Paris he remarked, "Yes it is we who made it, that is cubism".[3] In Britain, Edward Wadsworth, who supervised dazzle camouflage painting in the war, created a series of canvases after the war based on his dazzle work on ships. In Canada, Arthur Lismer used dazzle ships in some of his wartime compositions.[40] In America, Burnell Poole painted canvases of United States Navy ships in dazzle camouflage at sea.[41] The historian of camouflage Peter Forbes comments that the ships had a Modernist look, their designs succeeding as avant-garde or Vorticist art.[8]

In 2007, the art of camouflage, including the evolution of dazzle, was featured as the theme for a show at the Imperial War Museum.[42] In 2009, the Fleet Library at the Rhode Island School of Design exhibited its rediscovered collection of lithographic printed plans for the camouflage of American World War I merchant ships, in an exhibition titled "Bedazzled".[43]

In 2014, the Centenary Art Commission backed three dazzle camouflage installations in Britain:[44] Carlos Cruz-Diez covered the pilot ship Plantilla:MV in Liverpool's Canning Dock with bright multi-coloured dazzle artwork, as part of the city's 2014 Liverpool Biennial art festival;[45] and Tobias Rehberger painted HMS President, anchored since 1922 at Blackfriars Bridge in London, to commemorate the use of dazzle, a century on.[46][47] Peter Blake was commissioned to design exterior paintwork for Plantilla:MV, a Mersey Ferry, which he called "Everybody Razzle Dazzle", combining his trademark motifs (stars, targets etc.) with First World War dazzle designs.[48]

-

Two American ships in dazzle camouflage, painted by Burnell Poole, 1918

-

HMS President, painted by Tobias Rehberger in 2014 to commemorate the use of dazzle in World War I

Other uses

Patterns reminiscent of dazzle camouflage are sometimes used to mask test cars during trials.[49] During the 2015 Formula 1 testing period, the Red Bull RB11 car was painted in a scheme intended to confound rival teams' ability to analyse its aerodynamics.[50] The designer Adam Harvey has similarly proposed a form of camouflage reminiscent of dazzle for personal camouflage from face-detection technology. It attempts to block detection by facial recognition technologies such as DeepFace "by creating an 'anti-face'".[51] It uses occlusion, covering certain facial features; transformation, altering the shape or colour of parts of the face; and a combination of the two.[52] The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society has used dazzle patterns on its fleet since 2009.[53]

- ↑ a b c d e f Newark, Tim (2007). «Camouflage». Thames and Hudson / Imperial War Museum. p. 74.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Norman (4 April 1939). «Letters. Camouflage». The Times.

- ↑ a b Glover, Michael. "Now you see it... Now you don't" The Times. 10 March 2007.

- ↑ Wilkinson said that dazzle was a "method to produce an effect by paint in such a way that all accepted forms of a ship are broken up by masses of strongly contrasted colour, consequently making it a matter of difficulty for a submarine to decide on the exact course of the vessel to be attacked."[1]

- ↑ a b c Forbes, 2009. pp. 90–91

- ↑ Forbes, 2009. p. 97

- ↑ a b Forbes, 2009. p. 96

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Forbes, 2009. pp. 98–100

- ↑ Forbes, 2009. p. 92.

- ↑ Murphy, Robert Cushman (January 1917). «Marine camouflage». The Brooklyn Museum quarterly (Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences). 4–6: 35-39.

- ↑ Vegetius had recorded "Venetian blue" (bluish-green, the same colour as the sea) was used for ship camouflage during the Gallic Wars, when Julius Caesar had sent his scout ships to gather intelligence along the coast of Britain.[10]

- ↑ «Robert F. Sumrall». Navy Yard Associates. Consultado el 7 January 2016.

- ↑ Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; no se ha definido el contenido de las referencias llamadasForbes87 - ↑ Sumrall, Robert F. (February 1973). «Ship Camouflage (WWII): Deceptive Art». United States Naval Institute Proceedings. pp. 67-81.

- ↑ a b Willis, Sam. «How did an artist help Britain fight the war at sea?». British Broadcasting Corporation. Consultado el 7 January 2016.

- ↑ The equivalent for naval artillery at a range of 7000 m (7655,3 yd) would require a ship to travel at 7000 × 90/70 = Error de Lua en Módulo:ConvertirAux en la línea 469: attempt to perform arithmetic on local 'l' (a nil value). to achieve motion dazzle.

- ↑ Scott-Samuel, Nicholas E.; Baddeley, Roland; Palmer, Chloe E.; Cuthill, Innes C. (2011). «Dazzle Camouflage Affects Speed Perception». PLOS One 6 (6): e20233. PMC 3105982. PMID 21673797. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020233.

- ↑ Forbes, 2009. p. 87

- ↑ a b Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; no se ha definido el contenido de las referencias llamadasMurphy - ↑ Forbes, 2009. p. 88

- ↑ Fisher, Mark. "Secret history: how surrealism can win a war," The Times. 8 January 2006.

- ↑ Raven, Alan. «The Development of Naval Camouflage 1914–1945 Part I». Ship Camouflage. Consultado el 22 de mayo de 2015.

- ↑ In August 1917, HMS Alsatian was painted in a dazzle pattern, perhaps the first Royal Navy vessel to be camouflaged in this way.[22]

- ↑ Paulk, Ann Bronwyn (April 2003). «False Colors: Art, Design, and Modern Camouflage (review)». Modernism/modernity 10 (2): 402-404. doi:10.1353/mod.2003.0035.

- ↑ Williams, 2001. p. 35

- ↑ Williams, 2001. p. 40

- ↑ Hartcup, Guy (1979). Camouflage: the history of concealment and deception in war. Pen & Sword.

- ↑ Scott-Samuel, Nicholas E; Baddeley, Roland; Palmer, Chloe E; Cuthill, Innes C (June 2011). «Dazzle Camouflage Affects Speed Perception». PLoS ONE 6 (6): e20233. PMC 3105982. PMID 21673797. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020233.

- ↑ Stevens, M.; Yule, D.H.; Ruxton, G.D. (2008). «Dazzle coloration and prey movement». Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275 (1651): 2639-2643. PMC 2605810. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0877.

- ↑ Buskirk, Harold Van (1919). «Camouflage». Transactions of the Illuminating Engineering Society 14 (5): 225-229. Archivado desde el original el 4 de marzo de 2016.

- ↑ Thus we know, as Buskirk claimed, that less than 1% of the US merchant ships painted in dazzle were lost; what we do not know is how many non-camouflaged ships there were, so the comparative rates of loss cannot be calculated.

- ↑ a b Sumrall, Robert F. (February 1973). «Ship Camouflage (WWII): Deceptive Art». United States Naval Institute Proceedings: 67-81.

- ↑ Warneke, Jon; Herne, Jeff. «Royal Navy Colour Chips». Steelnavy.com. Consultado el 7 January 2012.

- ↑ Short, Randy. «USN Camouflage Measures». Snyder and Short Enterprises. Consultado el 27 July 2015.

- ↑ Brand, C. L. (26 February 1945). «Camouflage Instructions – Carriers, Cruisers, Destroyers, Destroyer Escorts, Assigned to the Pacific Fleet». Navy Department Bureau of Ships. Consultado el 8 April 2013.

- ↑ Asmussen, John. «Bismarck Paint Schemes». Consultado el 17 July 2015.

- ↑ Asmussen, John; Leon, Eric (2012). German Naval Camouflage Volume One 1939–1941. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-142-7.

- ↑ Forbes, 2009. p. 104

- ↑ Error en la cita: Etiqueta

<ref>no válida; no se ha definido el contenido de las referencias llamadasCampbell-Johnson, Rachel - ↑ Kelly, Gemey. «The Group of Seven and the Halifax Harbour Explosion: Focus on Arthur Lismer». Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Consultado el 10 June 2015.

- ↑ «"A Fast Convoy" by Burnell Poole». Naval History and Heritage Command. Consultado el 12 January 2016.

- ↑ Newark, Tim (2007). Camouflage. Thames & Hudson with Imperial War Museum. pp. Inside cover.

- ↑ «Fleet Library Special Collections: Dazzle Camouflage». Consultado el 7 January 2016.

- ↑ «Dazzle Ships». Consultado el 7 January 2016.

- ↑ «Liverpool Biennial – 2014 – Carlos Cruz-Diez». Consultado el 7 January 2015.

- ↑ Brown, Mark (14 July 2014). «First world war dazzle painting revived on ships in Liverpool and London». The Guardian. Consultado el 14 July 2014.

- ↑ «HMS President Dazzle Ship London». Consultado el 22 de mayo de 2015.

- ↑ Jones, Catherine (2 April 2015). «Razzle Dazzle Mersey Ferry unveiled by Sir Peter Blake». Liverpool Echo.

- ↑ Rabe, Mattias (9 March 2015). «Lamborghini kör med vidvinkel-extraljus i Norrland» (en swedish). Teknikens Värld. Consultado el 9 March 2015.

- ↑ Clarkson, Tom. «Formula One Testing:Tom Clarkson's Jerez Round-Up». BBC Sports. BBC News. Consultado el 22 February 2015.

- ↑ Burns, Janet (21 April 2015). «The Anti-Surveillance State: Clothes and Gadgets Block Face Recognition Technology, Confuse Drones and Make You (Digitally) Invisible». AlterNet. Consultado el 3 November 2015.

- ↑ Feng, Ranran; Prabhakaran, Balakrishnan (2013). «Facilitating Fashion Camouflage Art». Proceedings of the 21st ACM International Conference on Multimedia. MM '13 (ACM): 793-802. ISBN 978-1-4503-2404-5. doi:10.1145/2502081.2502121.

- ↑ «Sea Shepherd Fleet Gets Ready for Upcoming Campaigns». Sea Shepherd. 15 April 2011. Consultado el 5 January 2016.