Diferencia entre revisiones de «Alouatta pigra»

Traducción de la página en inglés |

(Sin diferencias)

|

Revisión del 13:47 23 jun 2009

| Guatemalan Black Howler[1] | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

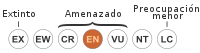

| Estado de conservación | ||

En peligro (UICN 3.1)[2] | ||

| Taxonomía | ||

| Reino: | Animalia | |

| Filo: | Chordata | |

| Clase: | Mammalia | |

| Orden: | Primates | |

| Familia: | Atelidae | |

| Género: | Alouatta | |

| Especie: |

A. pigra Lawrence, 1933 | |

| Sinonimia | ||

| ||

El mono aullador negro, o saraguato negro (Alouatta pigra) es una especie de mono del nuevo mundo de América Central. Se encuentra en Belice, Guatemala y México, ocupando la península de Yucatán. Vive en selvas tropicales perennes, semicaducas y de tierra baja [2][3]. También se conoce como “babuino” en Belice, aunque no se relaciona de cerca con los babuinos que viven en África ]].[4]. Se ve comúnmente en el Community Baboon Sanctuary y el Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary en Belice, y también en los diversos sitios arqueológicos encontrados en su distribución geográfica [3][4].

Descripción

The Guatemalan Black Howler is the largest of the howler monkey species and one of the largest of the New World Monkeys. Guatemalan Black Howler males are larger than those of any other Central American monkey species. On average, males weigh 11,4 kg (25,1 lb) and females weigh 6,4 kg (14,1 lb).[5] The body is between 521 y 639 mm (20,5 y 25,2 plg) in length, excluding tail.[6] The tail is between 590 y 690 mm (23,2 y 27,2 plg) long. Adults of both sexes have long, black hair and a prehensile tail, while infants have brown fur.[6] Males over 4 months old have a white scrotum.[3]

The Guatemalan Black Howler shares several adaptations with other species of howler monkey that allow it to pursue a folivorous diet, that is a diet with a large component of leaves. Its molars have high shearing crests, to help it eat the leaves,[5] and males have an enlarged hyoid bone near the vocal chords.[7] This hyoid bone amplifies the male Mantled Howler's calls, allowing it to locate other males without expending much energy, which is important since leaves are a low-energy food. Howling occurs primarily at dawn and at dusk.[6]

The Guatemalan Black Howler is diurnal and arboreal.[3] It lives in groups that generally contain one or two adult males, with a ratio of about 1.3 females for every male.[5][6] Groups generally have between two and 10 members, including juveniles, but groups as large as 16 members have been studied.[3][5] The home range is between 3 and 25 hectares.[6] Population density can exceed 250 monkeys per square kilometer in the Community Baboon Sanctuary in Belize.[2]

The Guatemalan Black Howler's diet includes mostly leaves and fruit. Flowers also make up a small part of the diet. The breadnut tree can provide as much as 86% of the monkey's diet during some seasons.[5][6]

As with other howler monkey species, the majority of the Guatemalan Black Howler's day is spent resting. Eating makes up about a quarter of the day, moving about 10% of the day, and the remainder of the day is spent in socializing and other activities.[5]

Females reach sexual maturity at four years, and males reach sexual maturity between six and eight years. Males leave their natal group upon reaching sexual maturity, but females generally remain with their natal group. They can live up to 20 years.[6]

EStado de conservación

The species is considered to be endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature because it is believed that the species population will decline by up to 60% over the next 30 years. Threats to the species include habitat loss, hunting, and capture as pets.[2]

The Guatemalan Black Howler belongs to the New World monkey family Atelidae, which contains howler monkeys, spider monkeys, woolly monkeys and muriquis. It is a member of the howler monkey genus Alouatta. No subspecies are recognized.[1]

Sympatría

The Guatemalan Black Howler is sympatric with the Mantled Howler along the edges of its range in Mexico and Guatemala near the Yucatan Peninsula.[2][8] One theory for how this sympatry occurred and why the Guatemalan Black Howler has such a restricted range is that the ancestors of the Guatemalan Black Howler and the Central American Squirrel Monkey migrated to Central America from South America during the late Miocene or Pliocene. However, passage through the isthmus of Panama later closed due to rising oceans, and later opened up to another wave of migration about 2 million years ago. These later migrants, ancestors to modern populations of White-headed Capuchins, Mantled Howlers and Geoffroy's Spider Monkeys, out-competed the earlier migrants, leading to the restricted range of the Guatemalan Black Howler (and the Central American Squirrel Monkey).[9]

References

- ↑ a b Groves, Colin (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. Mammal Species of the World (3ª edición). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 149. ISBN 0-8018-8221-4.

- ↑ a b c d e Marsh, L.K., Cuarón, A.D., Cortés-Ortiz, L., Shedden, A., Rodríguez-Luna, E. & de Grammont, P.C, (2008). «Alouatta pigra». Lista Roja de especies amenazadas de la UICN 2024 (en inglés). ISSN 2307-8235. Consultado el 26 October, 2008.

- ↑ a b c d e Emmons, L. (1997). Neotropical Rainforest Mammals A Field Guide (Second Edition edición). Chicago, Ill. ;London: Univ. of Chicago Pr. pp. 130-131. ISBN 0-226-20721-8.

- ↑ a b Hunter, L. & Andrew, D. (2002). Watching Wildlife Central America. Footscray, Vic.: Lonely Planet Publications. p. 150. ISBN 1-86450-034-4.

- ↑ a b c d e f Di Fiore, A. and Campbell, C. (2007). «The Atelines». En Campbell, C., Fuentes, A., MacKinnon, K., Panger, M., & Bearder, S., ed. Primates in Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 155-177. ISBN 978-0-19-517133-4.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Rowe, N. (1996). The Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates. East Hampton, N.Y.: Pogonias Press. p. 110. ISBN 0-9648825-0-7.

- ↑ Napier, J. & Napier, P. (1994). The Natural History of the Primates. The MIT Press. pp. 123-124. ISBN 9780262640336.

- ↑ Rylands, A., Groves, C., Mittermeier, R., Cortes-Ortiz, L., & Hines, J. (2006). «Taxonomy and Distributions of Mesoamerican Primates». En Estrada, A.; Garber, P.A.; Pavelka, M.S.M.; Luecke, L., ed. New Perspectives in the Study of Mesoamerican Primates. New York: Springer. pp. 47-55. ISBN 978-0-387-25854-6.

- ↑ Ford, S. (2006). «The Biogeographic History of Mesoamerican Primates». En Estrada, A.; Garber, P.A.; Pavelka, M.S.M.; Luecke, L., ed. New Perspectives in the Study of Mesoamerican Primates. New York: Springer. pp. 100-107. ISBN 978-0-387-25854-6. doi:10.1007/b136304.

External links

Wikispecies tiene un artículo sobre Guatemalan Black Howler.

Wikispecies tiene un artículo sobre Guatemalan Black Howler.- ARKive – images and movies of the Guatemalan black howler (Alouatta pigra)

- Infonatura