Usuario:Pato Lozano/Phage therapy

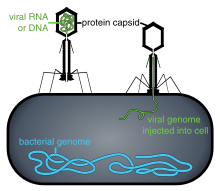

Phage therapy or viral phage therapy is the therapeutic use of bacteriophages to treat pathogenic bacterial infections.[1] Phage therapy has many potential applications in human medicine as well as dentistry, veterinary science, and agriculture.[2] If the target host of a phage therapy treatment is not an animal, the term "biocontrol" (as in phage-mediated biocontrol of bacteria) is usually employed, rather than "phage therapy".

They would have a high therapeutic index, that is, phage therapy would be expected to give rise to few side effects. Because phages replicate in vivo, a smaller effective dose can be used. On the other hand, this specificity is also a disadvantage; a phage will only kill a bacterium if it is a match to the specific strain. Consequently, phage mixtures are often applied to improve the chances of success, or samples can be taken and an appropriate phage identified and grown.

Bacteriophages are much more specific than antibiotics. They are typically harmless not only to the host organism, but also to other normal flora, such as those in the gut, to reduce the opportunistic infection.[3]

Phages tend to be more successful than antibiotics where there is a biofilm covered by a polysaccharide layer, which antibiotics typically cannot penetrate.[4] In the West, no therapies are currently authorized for use on humans, although phages for killing food poisoning bacteria (Listeria) are now in use.[5]

Phages are currently being used therapeutically to treat bacterial infections that do not respond to conventional antibiotics, particularly in Russia[6] and Georgia.[7][8][9] There is also a phage therapy unit in Wroclaw, Poland, established 2005, the only such centre in a European Union country.[10]

History[editar]

The discovery of bacteriophages was reported by Frederick Twort in 1915 and Felix d'Hérelle[11] in 1917. D'Hérelle said that the phages always appeared in the stools of Shigella dysentery patients shortly before they began to recover.[12] He "quickly learned that bacteriophages are found wherever bacteria thrive: in sewers, in rivers that catch waste runoff from pipes, and in the stools of convalescent patients."[13] Phage therapy was immediately recognized by many to be a key way forward for the eradication of bacterial infections. A Georgian, George Eliava, was making similar discoveries. He travelled to the Pasteur Institute in Paris where he met d'Hérelle, and in 1923 he founded the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia, devoted to the development of phage therapy. Phage therapy is used in Russia, Georgia and Poland.

In Russia, extensive research and development soon began in this field. In the United States during the 1940s commercialization of phage therapy was undertaken by Eli Lilly and Company.

While knowledge was being accumulated regarding the biology of phages and how to use phage cocktails correctly, early uses of phage therapy were often unreliable.[14] When antibiotics were discovered in 1941 and marketed widely in the U.S. and Europe, Western scientists mostly lost interest in further use and study of phage therapy for some time.[15]

Isolated from Western advances in antibiotic production in the 1940s, Russian scientists continued to develop already successful phage therapy to treat the wounds of soldiers in field hospitals. During World War II, the Soviet Union used bacteriophages to treat many soldiers infected with various bacterial diseases e.g. dysentery and gangrene. Russian researchers continued to develop and to refine their treatments and to publish their research and results. However, due to the scientific barriers of the Cold War, this knowledge was not translated and did not proliferate across the world.[16][17] A summary of these publications was published in English in 2009 in "A Literature Review of the Practical Application of Bacteriophage Research".[18]

There is an extensive library and research center at the George Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia. Phage therapy is today a widespread form of treatment in that region.[19]

As a result of the development of antibiotic resistance since the 1950s and an advancement of scientific knowledge, there has been renewed interest worldwide in the ability of phage therapy to eradicate bacterial infections and chronic polymicrobial biofilm (including in industrial situations[20]).

Phages have been investigated as a potential means to eliminate pathogens like Campylobacter in raw food[21] and Listeria in fresh food or to reduce food spoilage bacteria.[22] In agricultural practice phages were used to fight pathogens like Campylobacter, Escherichia and Salmonella in farm animals, Lactococcus and Vibrio pathogens in fish from aquaculture and Erwinia and Xanthomonas in plants of agricultural importance. The oldest use was, however, in human medicine. Phages have been used against diarrheal diseases caused by E. coli, Shigella or Vibrio and against wound infections caused by facultative pathogens of the skin like staphylococci and streptococci. Recently the phage therapy approach has been applied to systemic and even intracellular infections and the addition of non-replicating phage and isolated phage enzymes like lysins to the antimicrobial arsenal. However, actual proof for the efficacy of these phage approaches in the field or the hospital is not available.[22]

Some of the interest in the West can be traced back to 1994, when Soothill demonstrated (in an animal model) that the use of phages could improve the success of skin grafts by reducing the underlying Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection.[23] Recent studies have provided additional support for these findings in the model system.[24]

Although not "phage therapy" in the original sense, the use of phages as delivery mechanisms for traditional antibiotics constitutes another possible therapeutic use.[25][26] The use of phages to deliver antitumor agents has also been described in preliminary in vitro experiments for cells in tissue culture.[27]

In June 2015 the European Medicines Agency hosted a one-day workshop on the therapeutic use of bacteriophages[28] and in July 2015 the National Institutes of Health (USA) hosted a two-day workshop "Bacteriophage Therapy: An Alternative Strategy to Combat Drug Resistance".[29]

Potential benefits[editar]

Bacteriophage treatment offers a possible alternative to conventional antibiotic treatments for bacterial infection.[30] It is conceivable that, although bacteria can develop resistance to phage, the resistance might be easier to overcome than resistance to antibiotics.[31] Just as bacteria can evolve resistance, viruses can evolve to overcome resistance.[32]

Bacteriophages are very specific, targeting only one or a few strains of bacteria.[33] Traditional antibiotics have more wide-ranging effect, killing both harmful bacteria and useful bacteria such as those facilitating food digestion. The species and strain specificity of bacteriophages makes it unlikely that harmless or useful bacteria will killed when fighting an infection.

Some evidence shows the ability of phages to travel to a required site—including the brain, where the blood brain barrier can be crossed—and multiply in the presence of an appropriate bacterial host, to combat infections such as meningitis. However the patient's immune system can, in some cases, mount an immune response to the phage (2 out of 44 patients in a Polish trial[34]).

A few research groups in the West are engineering a broader spectrum phage, and also a variety of forms of MRSA treatments, including impregnated wound dressings, preventative treatment for burn victims, phage-impregnated sutures.[35] Enzybiotics are a new development at Rockefeller University that create enzymes from phage. These show potential for preventing secondary bacterial infections, e.g. pneumonia developing in patients suffering from flu and otitis.[cita requerida] Purified recombinant phage enzymes can be used as separate antibacterial agents in their own right.[36]

For some bacteria, such as multiple-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, there are no effective non-toxic antibiotics, but killing of this bacteria via intraperitoneal, intravenous, or intranasal route of phages in vivo has been shown to work in laboratory tests.[37]

Aplicación[editar]

Recolección[editar]

La manera más simple del tratamiento de fagos involucra la recolección local de agua que es probable que contenga cantidades grandes de bacterios y bacteriofagos, por ejemplo desagües, aguas residuales y otras fuentes.[7] También pueden ser extraídos de cadáveres.[cita requerida] Las muestras son tomadas y aplicadas a las bacterias que han de ser destruidas y han sido cultivadas en un medio de crecimiento.

Si las bacterias mueren, como generalmente pasa, la mezcla es centrifugada; los fagos son recolectados de la parte superior de la mezcla y pueden ser extraídos.

Las soluciones de fagos son probadas para ver cuáles muestran efectos de represión de crecimiento (lisogenia) o destrucción (lisis) de las bacterias objetivo. Los fagos que muestran lisis son posteriormente amplificados en cultivos de las bacterias objetivo, pasadas a través de un filtro para remover todo excepto los fagos, y después distribuídas.

Tratamiento[editar]

Los fagos son “bacterias específicas” y es por eso que en muchos casos es necesario tomar una muestra del paciente y cultivarla previo al tratamiento. Ocasionalmente, el aislamiento de los fagos terapéuticos pueden requerir unos cuantos meses para completarse, pero las clínicas generalmente conservan suministros de cócteles de fagos para las cepas bacterianas más comunes del área geográfica.

En la práctica los fagos son aplicados oralmente, tópicamente en heridas infectadas o esparcidos en otras superficies, o utilizados en durante cirugías. Las inyecciones son raramente utilizadas, para evitar riesgo de tener un rastro de contaminantes químicos que pueden estar presentes en la fase de amplificación de las bacterias, y reconociendo que el sistema inmune naturalmente pelea contra los virus que son introducidos al torrente sanguíneo o al sistema linfático.

El uso humano directo de los fagos es probable que sea seguro; en agosto y octubre del 2006, la Administración de comida y fármacos de los Estados Unidos de América aprobó el esparcimiento de carne y queso con fagos. La aprobación fue para ListShield and Listex (preparaciones de fagos enfocándose en Listeria monocytogenes). Esta fue la primera aprobación otorgada por la FDA y la USDA para aplicaciones basadas en fagos. Esta confirmación sobre la seguridad dentro del mundo científico abrió el camino para otras aplicaciones de fagos por ejemplo contra la Salmonella y E-coli (http://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/regulations/directives/fsis-directives)

La terapia de fagos se ha intentado para el tratamiento de una variedad de infecciones bacterianas incluyendo: laringitis, infecciones de la piel, disentería, conjuntivitis, periodontitis, gingivitis, sinusitis, infecciones del tracto urinario e infecciones intestinales, quemaduras, forúnculos,[7]biopelícula polimicrobiana en heridas crónicas, úlceras y sitios quirúrgicos infectados. [cita requerida]

En 2007 la fase 1/2 de pruebas clínicas fue completada en la Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital, Londres en infecciones Pseudomonas aeruginosa (otitis).[38][39][40] Documentos del estudio de la Fase 1/Fase 2 fueron publicados en agosto del 2009 en el Diario Clínico Otaringólogo.[41]

La fase 1 de las pruebas clínicas han sido completadas en el Southwest Regional Wound Care Center, Lubbock, Texas en la aprobación de un un cóctel de fagos contra bacterias, incluyendo P. aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli (mejor conocida como E. coli). [42] El cóctel de fagos para las pruebas clínicas fue desarrollado y suministrado por Intralytix.

Evaluaciones de la terapia de fagos indican que más pruebas clínicas y microbiológicas son necesarias para poder cumplir con los estándares actuales.[43]

Administración[editar]

Los fagos pueden generalmente ser liofilizados y convertidos en píldoras sin impactar en la eficacia materialmente.[7] Con temperatura estable de hasta 55 ºC y con vida útil de 14 meses algunos tipos de fagos han mostrado que pueden estar en una píldora.[7]

La aplicación en forma líquida es posible, almacenados perfectamente en viales refrigerados.[7]

La administración oral funciona mejor cuando se incluye un antiácido, así el número de fagos que sobreviven el paso por el estómago se incrementa.[7]

La administración tópica a menudo involucra la aplicación de gasas que son colocadas en el área que será tratada.[7]

Obstacles[editar]

The high bacterial strain specificity of phage therapy may make it necessary for clinics to make different cocktails for treatment of the same infection or disease because the bacterial components of such diseases may differ from region to region or even person to person.

In addition, due to the specificity of individual phages, for a high chance of success, a mixture of phages is often applied. This means that 'banks' containing many different phages must be kept and regularly updated with new phages.[44]

Further, bacteria can evolve different receptors either before or during treatment; this can prevent the phages from completely eradicating the bacteria.[7]

The need for banks of phages makes regulatory testing for safety harder and more expensive under current rules in most countries. Such a process would make it difficult for large-scale production of phage therapy. Additionally, patent issues (specifically on living organisms) may complicate distribution for pharmaceutical companies wishing to have exclusive rights over their "invention", which would discourage for-profit corporation from investing capital in the dissemination of this technology.

As has been known for at least thirty years, mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis have specific bacteriophages.[45] No lytic phage has yet been discovered for Clostridium difficile, which is responsible for many nosocomial diseases, but some temperate phages (integrated in the genome, also called lysogenic) are known for this species; this opens encouraging avenues but with additional risks as discussed below.

To work the virus has to reach the site of the bacteria, and viruses can sometimes reach places antibiotics cannot. For example, jazz bassist Alfred Gertler got a bacterial infection in his bones after breaking an ankle. A physician in the U.S. told him that the foot must be amputated. He refused and was largely bed ridden for four years until phage therapy at the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia, eliminated the bacterial infection.[12] Then he had surgery to repair his ankle and resumed his career and family life.[46]

Funding for phage therapy research and clinical trials is generally insufficient and difficult to obtain, since it is a lengthy and complex process to patent bacteriophage products. Scientists comment that 'the biggest hurdle is regulatory', whereas an official view is that individual phages would need proof individually because it would be too complicated to do as a combination, with many variables. Due to the specificity of phages, phage therapy would be most effective with a cocktail injection, which is generally rejected by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Researchers and observers predict that for phage therapy to be successful the FDA must change its regulatory stance on combination drug cocktails.[44] Public awareness and education about phage therapy are generally limited to scientific or independent research rather than mainstream media.[47]

The negative public perception of viruses may also play a role in the reluctance to embrace phage therapy.[48]

Legislation[editar]

Approval of phage therapy for use in humans has not been given in Western countries with a few exceptions. Washington and Oregon law allows naturopathic physicians to use any therapy that is legal any place in the world on an experimental basis.[49]

In Texas phages are considered natural substances and can be used in addition to (but not as a replacement for) traditional therapy; they've been used routinely in a wound care clinic in Lubbock, TX, since 2006.[50]

In 2013 "the 20th biennial Evergreen International Phage Meeting ... conference drew 170 participants from 35 countries, including leaders of companies and institutes involved with human phage therapies from France, Australia, Georgia, Poland and the United States."[51]

Safety[editar]

Much of the difficulty in obtaining regulatory approval is proving safety for using a self-replicating entity which has the capability to evolve.[20]

As with antibiotic therapy and other methods of countering bacterial infections, endotoxins are released by the bacteria as they are destroyed within the patient (Herxheimer reaction). This can cause symptoms of fever; in extreme cases toxic shock (a problem also seen with antibiotics) is possible.[52] Janakiraman Ramachandran[53] argues that this complication can be avoided in those types of infection where this reaction is likely to occur by using genetically engineered bacteriophages which have had their gene responsible for producing endolysin removed. Without this gene the host bacterium still dies but remains intact because the lysis is disabled. On the other hand, this modification stops the exponential growth of phages, so one administered phage means one dead bacterial cell.[9] Eventually these dead cells are consumed by the normal house-cleaning duties of the phagocytes, which utilise enzymes to break down the whole bacterium and its contents into harmless proteins, polysaccharides and lipids.[54]

Temperate (or Lysogenic) bacteriophages are not generally used therapeutically, as this group can act as a way for bacteria to exchange DNA; this can help spread antibiotic resistance or even, theoretically, make the bacteria pathogenic (see Cholera). Carl Merril claimed that harmless strains of corynebacterium may have been converted into c. diphtheriae that "probably killed a third of all Europeans who came to North America in the seventeenth century".[55] Fortunately, many phages seem to be lytic only with negligible probability of becoming lysogenic.[56]

Efficacy[editar]

In Russia, mixed phage preparations may have a therapeutic efficacy of 50%. This equates to the complete cure of 50 of 100 patients with terminal antibiotic-resistant infection. The rate of only 50% is likely to be due to individual choices in admixtures and ineffective diagnosis of the causative agent of infection.[57]

Other animals[editar]

Brigham Young University is currently researching the use of phage therapy to treat American foulbrood in honeybees.[58][59]

Cultural impact[editar]

The 1925 novel and 1926 Pulitzer prize winner Arrowsmith used phage therapy as a plot point.[60][61][62]

Greg Bear's 2002 novel Vitals features phage therapy, based on Soviet research, used to transfer genetic material.

The 2012 collection of military history essays about the changing role of women in warfare, "Women in War - from home front to front line" includes a chapter featuring phage therapy: "Chapter 17: Women who thawed the Cold War".[63]

Notes[editar]

- ↑ Silent Killers: Fantastic Phages?, by David Kohn, CBS News: 48 Hours Mystery.

- ↑ McAuliffe et al. "The New Phage Biology: From Genomics to Applications" (introduction) in Mc Grath, S. and van Sinderen, D. (eds.) Bacteriophage: Genetics and Molecular Biology Caister Academic Press ISBN 978-1-904455-14-1

- ↑ "Phage Therapy: Concept to Cure". Frontiers in Microbiology 3. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00238. PMC 3400130. PMID 22833738.

- ↑ Aguita, Maria. «Combatting Bacterial Infection». LabNews.co.uk. Consultado el 5 de mayo de 2009.

- ↑ Pirisi A (2000). «Phage therapy—advantages over antibiotics?». Lancet 356 (9239): 1418. PMID 11052592. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74059-9.

- ↑ «Eaters of bacteria: Is phage therapy ready for the big time?». Discover Magazine. Consultado el 12 de abril de 2013.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i BBC Horizon: Phage — The Virus that Cures 1997-10-09

- ↑ Parfitt T (2005). «Georgia: an unlikely stronghold for bacteriophage therapy». Lancet 365 (9478): 2166-7. PMID 15986542. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66759-1.

- ↑ a b Thiel, Karl (January 2004). «Old dogma, new tricks—21st Century phage therapy». Nature Biotechnology (London UK: Nature Publishing Group) 22 (1): 31-36. PMID 14704699. doi:10.1038/nbt0104-31. Consultado el 15 de diciembre de 2007.

- ↑ http://www.iitd.pan.wroc.pl/en/clinphage2015

- ↑ «[Bacteriophages as antibacterial agents]». Harefuah (en hebrew) 143 (2): 121-5, 166. 2004. PMID 15143702. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ a b Häusler (2006, ch. 1, at the limits of medicine)

- ↑ Kuchment (2012, p. 11)

- ↑ Kutter, E; De Vos, D; Gvasalia, G; Alavidze, Z; Gogokhia, L; Kuhl, S; Abedon, ST (January 2010). «Phage therapy in clinical practice: treatment of human infections». Current pharmaceutical biotechnology 11 (1): 69-86. PMID 20214609. doi:10.2174/138920110790725401.

- ↑ Hanlon GW (2007). «Bacteriophages: an appraisal of their role in the treatment of bacterial infections». Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30 (2): 118-28. PMID 17566713. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.04.006.

- ↑ "Stalin's Forgotten Cure". Science, 25 October 2002 v.298

- ↑ Summers WC (2001). «Bacteriophage therapy». Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55: 437-51. PMID 11544363. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.437.

- ↑ Nina Chanishvili, 2009, "A Literature Review of the Practical Application of Bacteriophage Research", 184p.

- ↑ Kuchment, Anna (2011); Häusler, Thomas (2006)

- ↑ a b «KERA Think! Podcast: Viruses are Everywhere!». 16 de junio de 2011. Consultado el 4 de junio de 2012. (audio)

- ↑ «Cost-utility analysis to control Campylobacter on chicken meat: dealing with data limitations». Risk Anal. 27 (4): 815-30. 2007. PMID 17958494. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2007.00925.x. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ a b Mc Grath S and van Sinderen D (editors). (2007). Bacteriophage: Genetics and Molecular Biology (1st edición). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-14-1. [1].

- ↑ Soothill JS (1994). «Bacteriophage prevents destruction of skin grafts by Pseudomonas aeruginosa». Burns 20 (3): 209-11. PMID 8054131. doi:10.1016/0305-4179(94)90184-8.

- ↑ «Phage therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a mouse burn wound model». Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51 (6): 1934-8. 2007. PMC 1891379. PMID 17387151. doi:10.1128/AAC.01028-06. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Targeted drug-carrying bacteriophages as antibacterial nanomedicines». Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51 (6): 2156-63. 2007. PMC 1891362. PMID 17404004. doi:10.1128/AAC.00163-07. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Targeting antibacterial agents by using drug-carrying filamentous bacteriophages». Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50 (6): 2087-97. 2006. PMC 1479106. PMID 16723570. doi:10.1128/AAC.00169-06. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «Killing cancer cells by targeted drug-carrying phage nanomedicines». BMC Biotechnol. 8: 37. 2008. PMC 2323368. PMID 18387177. doi:10.1186/1472-6750-8-37. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/events/2015/05/event_detail_001155.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c3

- ↑ https://respond.niaid.nih.gov/conferences/bacteriophage/Pages/Agenda.aspx

- ↑ «Bacteriophage therapy for the treatment of infections». Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs (London, England : 2000) 10 (8): 766-74. August 2009. PMID 19649921. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ «What is Phage Therapy?». phagetherapycenter.com. Consultado el 29 de noviembre de 2014.

- ↑ Abedon ST (2012). Salutary contributions of viruses to medicine and public health. In: Witzany G (ed). Viruses: Essential Agents of Life. Springer. 389-405. ISBN 978-94-007-4898-9.

- ↑ «Bacteriophages: potential treatment for bacterial infections». BioDrugs 16 (1): 57-62. 2002. PMID 11909002. doi:10.2165/00063030-200216010-00006. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ "Non-antibiotic therapies for infectious diseases." by Christine F Carson, and Thomas V Riley Communicable Diseases Intelligence Volume 27 Supplement, May 2003. Australian Dept of health website

- ↑ Scientists Engineer Viruses To Battle Bacteria : NPR

- ↑ «Bacteriophage endolysins as a novel class of antibacterial agents». Experimental Biology and Medicine (Maywood, N.J.) 231 (4): 366-77. April 2006. PMID 16565432. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Bogovazova, GG; Voroshilova, NN; Bondarenko, VM (1991). «The efficacy of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteriophage in the therapy of experimental Klebsiella infection». Zhurnal mikrobiologii, epidemiologii, i immunobiologii (4): 5-8. PMID 1882608.

- ↑ «Press & News». Consultado el 13 de diciembre de 2007.

- ↑ «biocontrol.ltd.uk». Consultado el 13 de diciembre de 2007.

- ↑ «biocontrol-ltd.com». Consultado el 30 de abril de 2008.

- ↑ Wright, A.; Hawkins, C.H.; Änggård, E.E.; Harper, D.R. (2009). «A controlled clinical trial of a therapeutic bacteriophage preparation in chronic otitis due to antibiotic-resistantPseudomonas aeruginosa; a preliminary report of efficacy». Clinical Otolaryngology 34 (4): 349-57. PMID 19673983. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01973.x.

- ↑ Rhoads DD, Wolcott RD, Kuskowski MA, Wolcott BM, Ward LS, Sulakvelidze A (2009). Bacteriophage therapy of venous leg ulcers in humans: results of a phase I safety trial. J Wound Care. 2009 Jun;18(6):237-8, 240-3.

- ↑ Brüssow, H (2005). «Phage therapy: The Escherichia coli experience». Microbiology (Reading, England) 151 (Pt 7): 2133-40. PMID 16000704. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27849-0.

- ↑ a b Keen, E. C. (2012). «Phage Therapy: Concept to Cure». Frontiers in Microbiology 3: 238. PMC 3400130. PMID 22833738. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00238.

- ↑ Graham F. HATFULL 12 - Mycobacteriophages : Pathogenesis and Applications, pages 238-255 (in Waldor, M.K., D.I. Friedman, and S.L. Adhya, Phages: Their role in bacterial pathogenesis and biotechnology, 2005, University of Michigan; Sankar L. Adhya, National Institutes of Health: ASM Press).

- ↑ Kutter, Betty (c. 2009), Our First Adventure With Phage Therapy: Alfred's Story, Olympia, WA: Evergreen College, consultado el 27 de abril de 2015.

- ↑ Brüssow, H 2007. Phage Therapy: The Western Perspective. in S. McGrath and D. van Sinderen (eds.) Bacteriophage: Genetics and Molecular Biology, Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, UK. ISBN 978-1-904455-14-1

- ↑ «European regulatory conundrum of phage therapy». Future Microbiol 2 (5): 485-91. 2007. PMID 17927471. doi:10.2217/17460913.2.5.485. Parámetro desconocido

|vauthors=ignorado (ayuda) - ↑ Faltys, Doris (4 August 2013), «Evergreen Researcher Dr. Kutter Announces 'There's a Phage for That'», Thurston Talk (Olympia, Washington), consultado el 1 de marzo de 2015.

- ↑ Kuchment (2011, ch. 12, pp. 115-118): In addition to mentioning that Texas law allows physicians to use "natural substances" like phages in addition to (but not in lieu of) standard medical practice, Kuichment says, "In June 2009 [Dr. Randall Wolcott's] study was published in the Journal of Wound Care."

- ↑ December 2013 Faculty Spotlight, Olympia, WA: Evergreen College, December 2013, consultado el 1 de marzo de 2015.

- ↑ Evergreen PHAGE THERAPY: BACTERIOPHAGES AS ANTIBIOTICS

- ↑ Stone, Richard. "Stalin's Forgotten Cure." Science Online 282 (25 October 2002).

- ↑ Fox, Stuart Ira (1999). Human Physiology -6th ed.. McGraw-Hill. pp. : 50,55,448,449. ISBN 0-697-34191-7.

- ↑ Kuchement (2011, p. 94)

- ↑ Kuchement (2011, ch. 6, p. 63): "[T]he Hirszfeld Institute [in Poland] has almost always done its research studies in the absence of double-bind controls ... . But the sheer quantity of cases, combined with the fact that nearly all the cases involve patients who failed to respond to antibiotics, is persuasive."

- ↑ В.Н.Крылов (5 April 2007). «фаготерапия». Consultado el 29 de noviembre de 2014.

- ↑ «Bee Killers: Using Phages Against Deadly Honeybee Diseases». youtube.com. Consultado el 29 de noviembre de 2014.

- ↑ «Using microscopic bugs to save the bees». news.byu.edu. Consultado el 1 de diciembre de 2014.

- ↑ Summers WC (1991). «On the origins of the science in Arrowsmith: Paul de Kruif, Felix d'Herelle, and phage». J Hist Med Allied Sci 46 (3): 315-32. PMID 1918921. doi:10.1093/jhmas/46.3.315.

- ↑ «Phage Findings». Time. 3 de enero de 1938. Consultado el 13 de diciembre de 2007.

- ↑ «SparkNotes: Arrowsmith: Chapters 31–33». Consultado el 13 de diciembre de 2007.

- ↑ http://www.winstonchurchill.org/publications/chartwell-bulletin/bulletin-48-jun-2012/churchill-the-wartime-feminist

References[editar]

- Kuchment, Anna (2011), The Forgotten Cure: The Past and Future of Phage Therapy, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4614-0250-3.

- Häusler, Thomas (2006), Virus vs. Superbug: A solution to the antibiotic crisis?, Macmillan, p. 48, ISBN 978-0-230-55193-0.

External links[editar]

- Thiel, Karl (2004). «Old dogma, new tricks—21st Century phage therapy». Nature Biotechnology 22 (1): 31-6. PMID 14704699. doi:10.1038/nbt0104-31.

- Popsci: The Next Phage

- Bacteriophage (Journal)

- Elkadi, Omar Anwar (2014). «Phage therapy: The new old antibacterial therapy». El Mednifico Journal 2 (3): 311. doi:10.18035/emj.v2i3.202.