Dryopithecus

| Dryopithecus | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rango temporal: 12 Ma - 9 Ma Mioceno | ||

Recreación de Dryopithecus fontani | ||

| Taxonomía | ||

| Reino: | Animalia | |

| Filo: | Chordata | |

| Clase: | Mammalia | |

| Orden: | Primates | |

| Superfamilia: | Hominoidea | |

| Familia: | Hominidae | |

| Subfamilia: | Homininae | |

| Tribu: | Dryopithecini | |

| Género: |

Dryopithecus † Lartet, 1856 | |

| Especies | ||

| ||

Dryopithecus es un género extinto de primates homínidos que vivió en el este de África durante el Mioceno superior.

Sus restos han sido encontrados por toda Europa hasta el norte de la India. La edad de los fósiles hallados oscila entre los 20 y 8 millones de años.

Se especuló con que el hombre surgió de la línea del Dryopithecus. Algunos autores consideran que Dryopithecus y sus parientes deben tratarse como una subfamilia (Dryopithecinae) de la familia Hominidae y que de ella bien pudieron derivarse tanto los ponginos como los homininos.[1]

Hispanopithecus laietanus fue descrito inicialmente como una especie de este género (como Dryopithecus laietanus).[1]

Etimología[editar]

El nombre del género Dryopithecus proviene del griego antiguo δρῦς drũs, que significa 'roble' y πίθηκος pithekos que significa 'mono', porque el autor del taxón creía que habitaba en un bosque de robles o pinos en un entorno similar al de la Europa actual.[2]

Taxonomía[editar]

Los primeros fósiles de Dryopithecus fueron descritos en los Pirineos franceses por el paleontólogo francés Édouard Lartet en 1856, tres años antes de que Charles Darwin publicara su obra El origen de las especies.[3] Autores posteriores observaron similitudes con los grandes simios africanos modernos. En su obra El origen del hombre, Darwin señaló brevemente que el Dryopithecus ponía en duda el origen africano de los simios:

...it is somewhat more probable that our early progenitors lived on the African continent than elsewhere. But it is useless to speculate on this subject; for two or three anthropomorphous apes, one the Dryopithecus of Lartet, nearly as large as a man, and closely allied to Hylobates, existed in Europe during the Miocene age; and since so remote a period the earth has certainly undergone many great revolutions, and there has been ample time for migration on the largest scale.[4]...es algo más probable que nuestros primeros antepasados vivieran en el continente africano que en otros lugares. Pero es inútil especular sobre este tema, ya que dos o tres simios antropomorfos, uno de ellos el Dryopithecus de Lartet, casi tan grande como un hombre y estrechamente relacionado con los Hylobates, existieron en Europa durante la era del Mioceno; y desde un período tan remoto la Tierra ha experimentado ciertamente muchas grandes revoluciones, y ha habido tiempo suficiente para migraciones a gran escala.Charles Darwin

La taxonomía de los Dryopithecus ha sido objeto de mucha controversia, ya que nuevos especímenes han servido de base para crear una nueva especie o género basándose en pequeñas diferencias, lo cual ha dado lugar a varias especies ya desaparecidas.[5] En la década de 1960, todos los simios no humanos se clasificaron en la familia Pongidae, ahora obsoleta, y los simios extintos en Dryopithecidae.[5] En 1965, el paleoantropólogo inglés David Pilbeam y el paleontólogo estadounidense Elwyn L. Simons separaron el género, que en ese momento incluía especímenes de todo el Viejo Mundo, en tres subgéneros: Dryopithecus en Europa, Sivapithecus en Asia y Proconsul en África. Posteriormente, se debatió si cada uno de estos subgéneros debía ser elevado a género. En 1979, Sivapithecus fue elevado a género, y Dryopithecus se subdividió de nuevo en los subgéneros Dryopithecus en Europa, y Proconsul, Limnopithecus y Rangwapithecus en África.[6] Desde entonces, se asignaron y movieron varias especies más, y en el siglo XXI el género incluía a las especias D. fontani, D. brancoi, D. laietanus y D. crusafonti.[7][8][9][10] Sin embargo, el descubrimiento en 2009 de un cráneo parcial de D. fontani hizo que muchos de ellos fueran divididos en géneros diferentes, como el recién erigido Hispanopithecus, ya que parte de la confusión fue causada por la naturaleza fragmentaria del holotipo de Dryopithecus con características diagnósticas vagas e incompletas.[11][5]

| Distribución de Dryopithecus en Europa |

|---|

Actualmente, sólo existe una especie incuestionable, D. fontani. Los especímenes de esta son:

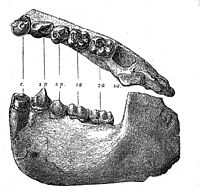

- Holotipo MNHNP AC 36, tres piezas de una mandíbula masculina con dientes proveniente de Saint-Gaudens en los Pirineos franceses.[5][12] Basándose en el desarrollo dental en chimpancés, tenía entre 6 y 8 años, y varias características diagnósticas realizadas a partir de este holotipo se perderían en D. fontani adultos. También se han descubierto en el mismo yacimiento un hueso parcial del brazo del húmero izquierdo, una mandíbula adicional (MNHNP 1872-2), una mandíbula inferior izquierda y cinco dientes aislados.[13][14]

- Un incisivo superior, NMB G.a.9., y un molar superior femenino, FSL 213981, provenientes de Saint-Alban-de-Roche, Francia.[15]

- Un rostro parcial masculino, IPS35026, y un fémur, IPS41724, procedentes del Vallès Penedès en Cataluña, España.[11][5]

- Una mandíbula femenina con dientes, LMK-Pal 5508, procedente de St. Stefan, Carintia, Austria de hace 12,5 millones de años, que podría considerarse una especie separada, Dryopithecus carinthiacus.[5][16][17]

Dryopithecus se clasifica en la tribu de homínidos homónima Dryopithecini, junto con Hispanopithecus, Rudapithecus, Ouranopithecus, Anoiapithecus y Pierolapithecus, aunque los dos últimos podrían pertenecer a Dryopithecus, los dos primeros podrían ser sinónimos, y los tres primeros también podrían incluirse en sus propias tribus.[5][18] Dryopithecini se ha considerado una rama de los orangutanes (Ponginae), un ancestro de los simios africanos y los humanos (Homininae), o una rama propia (Dryopithecinae).[19][20][21][22][18][23]

Dryopithecus formó parte de una radiación adaptativa de homínidos en los bosques en expansión de Europa en los climas cálidos del Óptimo Climático del Mioceno, posiblemente descienda de los simios africanos del Mioceno temprano o medio que se diversificaron en la extinción del Mioceno medio (un evento de enfriamiento). Es posible que los homínidos evolucionasen primero en Europa o Asia, y luego emigrasen a África.[24][5][25]

| Hominoidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Véase también[editar]

Referencias[editar]

- ↑ a b Alba, David M. y Moyà, S. (2012) Pierolapithecus y la evolución de los homínidos. Investigación y Ciencia, 435: 10-12

- ↑ Cameron, D. W. (2004). Hominid Adaptations and Extinctions. UNSW Press. pp. 138-139. ISBN 978-0-86840-716-6.

- ↑ Lartet, É. (1856). "Note sur un grand Singe fossile qui se rattache au groupe des Singes Supérieurs". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris (en francés). 43: 219–223.

- ↑ Darwin, C. (1875). The Descent of Man. D. Appleton and Company. p. 199.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Begun, D. R. (2018). «Dryopithecus». Dryopithecus. Wiley Online Library. pp. 1-4. ISBN 9781118584422. doi:10.1002/9781118584538.ieba0143.

- ↑ Szalay, F. S.; Delson, E. (1979). Evolutionary History of the Primates. Academic Press. pp. 470-490. ISBN 978-1-4832-8925-0.

- ↑ Merceron, G.; Schulz, E.; Kordos, L.; Kaiser, T. M. (2007). «Paleoenvironment of Dryopithecus brancoi at Rudabánya, Hungary: evidence from dental meso- and micro-wear analyses of large vegetarian mammals». Journal of Human Evolution 53 (4): 331-349. PMID 17719619. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.04.008.

- ↑ Kordos, L.; Begun, D. R. (2001). «A new cranium of Dryopithecus from Rudabánya, Hungary». Journal of Human Evolution 41 (6): 689-700. PMID 11782114. doi:10.1006/jhev.2001.0523.

- ↑ Moyà-Solà, S.; Köhler, M. (1996). «A Dryopithecus skeleton and the origins of great-ape locomotion». Nature 379 (6,561): 156-159. Bibcode:1996Natur.379..156M. PMID 8538764. doi:10.1038/379156a0.

- ↑ Begun, D. R. (1992). «Dryopithecus crusafonti sp. nov., a new Miocene Hominoid species from Can Ponsic (northeastern Spain)». American Journal of Physical Anthropology 87 (3): 291-309. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330870306.

- ↑ a b Moyà-Solà, S.; Köhler, M.; Alba, D. M. (2009). «First partial face and upper dentition of the Middle Miocene hominoid Dryopithecus fontani from Abocador de Can Mata (Vallès-Penedès Basin, Catalonia, NE Spain): taxonomic and phylogenetic implications». American Journal of Physical Anthropology 139 (2): 126-145. PMID 19278017. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20891.

- ↑ Casanovas-Vilar, C.; Alba, D. M.; Garcés, M.; Robles, J. M.; Moyà-Solà, S. (2011). «Updated chronology for the Miocene hominoid radiation in Western Eurasia». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (14): 5554-5559. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5554C. PMC 3078397. PMID 21436034. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018562108.

- ↑ Simons, E. L.; Meinel, W. (1983). «Mandibular ontogeny in the Miocene great ape Dryopithecus». International Journal of Primatology 4 (4): 331-337. doi:10.1007/BF02735598.

- ↑ Pilbeam, D.; Simons, E. L. (1971). «Biological sciences: humerus of Dryopithecus from Saint Gaudens, France». Nature 229 (5,284): 406-407. Bibcode:1971Natur.229..406P. PMID 4926991. doi:10.1038/229406a0.

- ↑ de los Ríos, M. P.; Alba, D. M.; Moyà-Solà, S. (2013). «Taxonomic attribution of the La Grive hominoid teeth». American Journal of Physical Anthropology 151 (4): 558-565. PMID 23754569. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22297.

- ↑ Fuss, J.; Uhlig, G.; Böhme, M. (2018). «Earliest evidence of caries lesion in hominids reveal sugar-rich diet for a Middle Miocene dryopithecine from Europe». PLOS ONE 13 (8): e0203307. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1303307F. PMC 6117023. PMID 30161214. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0203307.

- ↑ Mottl, V. M. (1957). Bericht über die neuen Menschenaffenfunde aus Österreich, von St. Stefan im Lavanttal, Kärnten. Carinthia II. [Report on new apes from Austria, from St. Stefan im Lavanttal, Carinthia. Carinthia II.] (en alemán) 67. pp. 39-84.

- ↑ a b de los Ríos, M. P. (2014). The craniodental anatomy of Miocene apes from the Vallès-Penedès Basin (Primates: Hominidae): Implications for the origin of extant great apes (PhD). Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. pp. 20-21. S2CID 90027032.

- ↑ Alba, D. M. (2012). «Fossil apes from the Vallès‐Penedès basin». Evolutionary Anthropology 21 (6): 254-269. PMID 23280922. doi:10.1002/evan.21312.

- ↑ Begun, D. R. (2005). «Sivapithecus is east and Dryopithecus is west, and never the twain shall meet». Anthropological Science 113 (1): 53-64. doi:10.1537/ase.04S008.

- ↑ Begun, D. R. (2009). «Dryopithecins, Darwin, de Bonis, and the European origin of the African apes and human clade». Geodiversitas 31 (4): 789-816. doi:10.5252/g2009n4a789.

- ↑ Begun, D. R.; Nargolwalla, M. C.; Kordos, L. (2012). «European Miocene hominids and the origin of the African ape and human clade». Evolutionary Anthropology 21 (1): 10-23. PMID 22307721. doi:10.1002/evan.20329.

- ↑ Köhler, M.; Moyà-Solà, S.; Alba, D. M. (2001). «Eurasian hominoid evolution in the light of recent Dryopithecus findings». En de Bonis, L.; Koufos, G. D.; Andrews, eds. Hominoid evolution and climatic change in Europe 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66075-4.

- ↑ Begun, D. R. (1992). «Dryopithecus crusafonti sp. nov., a new Miocene Hominoid species from Can Ponsic (northeastern Spain)». American Journal of Physical Anthropology 87 (3): 291-309. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330870306.

- ↑ Begun, D. R.; Nargolwolla, M. C.; Hutchinson, M. P. (2006). «Primate evolution in the Pannionian Basin: In situ evolution, dispersals, or both?». Beiträge zur Paläontologie 30: 43-56.